Anna gets a call from Bob and pops round to his office at the appointed time. Bob greets her and offers her coffee. She has had mixed feelings about this appointment. On one hand she is immediately suspicious. She does not normally get invited to have coffee with the CEO so what could he want? She had asked Jason but he either didn’t know or wasn’t saying. She hoped this was not another senior member of staff who was about to become unprofessional. On the other hand she is ambitious and has been mixing with directors quite a bit recently so this might be opportunity calling. She just hopes it isn’t going to be the sort of opportunity that ambitious Hollywood starlets seem to go in for.

After a few moments with Bob it all comes terribly clear. He is totally professional, he is not about to sack her but the news is even worse. He wants her to put together a viability study for the e-Trolley pilot project to be used as an example of best practice within the organisation.

‘What I need’, Bob says, ‘is a really full and professional study to show how these things ought to be done. I want you to understand that this study will set a standard for all future projects. I want you to take your time with it, get it absolutely right, and use all the expert help you can get and please be as dispassionate and honest as you can be.’

Anna thinks quickly and says: ‘So I can take a suitable current or just-about-to-start project and do a viability study to set a standard for future viability studies?’

‘Not quite’, smiles Bob, ‘We need complete the e-Trolley pilot project and use it to kill two birds with one trolley.’

Anna is faced with a significant challenge: she knows that people that run major, high profile projects take major, high profile risks with their careers. She read in a project management book once that the critical path in every project runs right past the chief executive’s garden gate. If you are very noticeable at work you are at the point of greatest personal risk. Everyone always thinks they have a better way of doing everything but when it is the ultimate boss you have to listen - and obey. Or at least seem to obey. In the world of project management it is much better to be mostly out of sight.

Anna now has a high profile project and Bob is asking her to increase its profile by leaps and bounds.

She realises that she may not be the ideal person for this assignment and says: ‘I am delighted you thought of me but I guess Jason is much more expert at this kind of thing that I am. Does he know about this?’

‘Oh, yes he does and thoroughly approves. You see if Jason did this study it might seem like a family matter. It doesn’t matter why or if it’s fair or not, people will not see the study as being independent. Also Jason freely admits to being a bit if a theorist when it comes to projects – he will help you a lot with the theory but he probably doesn’t have much more practical experience than you have.’

‘What time scale do you have in mind for this report?’

Bob says that he has spoken to her Director who has released her from some other rather boring work and freed up two days a week for the next month. ‘Is that OK?’

‘I don’t really know at this stage as this is not something I have done before but I’ll get back to you in two weeks if I think there is going to be a problem.’

Bob smiles and thinks that he would have made the very same response, ‘Very sensible. I think you’ll do fine.’

‘In that case’, Anna says fighting a rising tide of panic, ’I’ll get right on with it. Just a few questions – you know the amount of knowledge I have about this project is actually very small - what have you in mind for the e-Trolley trial?’

‘Ah, yes, well I think we should try and build a few prototype e-Trolleys and get a few outlets to give them a go for a few weeks at least. We may not be able to run the weighing systems or test the RFID function in this pilot, but it would be good if we could. But we really must be able to run the automatic connection with the tills otherwise the whole trial will be a waste of time. I guess I’m really looking to this project to test the whole idea in reality before we commit to a major roll out. I cannot imagine us changing the layout of any stores for the trial but if this goes well we will have major refit programme running in parallel with the e-Trolley programme and roll out across all, or at least most, stores.

‘Don’t forget this project is only the trial so the benefits are hazy – what we are trying to do here is to test the ideas so that we can decide on the major rollout of the e-Trolley

‘Whoever makes a success of this will find themselves running the single most important programme in the company next year.’

‘There is another reason for that last statement. I am on a mission to bring this company into the 21st century and I want to establish much better controls over our projects – how we choose them, how we run them and what we get back from them. I do not want a hugely expensive and unhelpful set of complex processes – the sort of thing we might easily end up from a major consultancy - but I do want to put in place some simple controls. I hope we will run the pilot project according to good practice – I want this to be a shining example of how a project ought to be done.

‘So by running this project you will have the best knowledge of our new programme and project management framework.

‘So what are you waiting for?’

Anna sets a new world record for the obstacle course from Bob’s office to the general office. She wades through the deeply piled carpet, sidesteps the coffee tray being delivered to the board room, and dives into the executive lift, fidgets as the lift slowly lowers itself down three floors, runs across the lift lobby, past the post room, through the double doors into the general office and into her own cubicle. She has the framework up and running as fast as her computer can cope without even looking at her email in-tray and without giving a customary stroke to the small furry purple racoon glued to her monitor.

During her blind dash numerous thoughts ran round her brain. Bob obviously thought he was motivating her by hanging out the carrot of ‘the most important project in the company’ but this to Anna is the most worrying thing of all. If, by some miracle and enough late nights, she succeeds with the e-Trolley trial project she gets another chance to screw up in front of the CEO and everyone else in an even bigger project. A future spending more evenings hunched over a laptop trying not to nibble chocolates beckons. This she feels is about as motivating to her as a mousetrap is to a mouse. It should have a huge sign over it saying ‘Keep Away – Don’t be tempted.’

Also, she thinks, what was that about weighing and RFID?

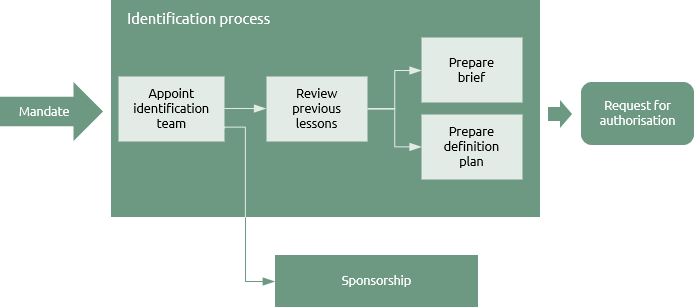

As she calms down she does remember that the project will be interesting and if she can get through the project and survive she will have a great new paragraph on her CV and will have achieved something very important for the company and for herself. She just needs to make sure she does this on her own terms. It certainly will not be humdrum and boring and she will get to meet all sorts of new people and that is always an attraction for people like Anna. Feeling more positive she searches through the framework for the identification process and finds it looks like this:

In this case Anna realises that she doesn’t need to implement the full process. She also realises that the project sponsor and programme sponsor are both taken by Bob at the moment. She of course is the project manager (otherwise known, she thinks, as the sacrificial lamb) and Jason is the project and programme support.

She wonders what life would be like in a mature organisation where the project sponsor and support function were experienced people who know exactly what their roles were and where they are going.

She thinks that she is supposed to have a project mandate by this stage and maybe that arrived verbally from Bob.

She wonders if she should be working towards a project brief or something further down the line.

She considers that the e-Trolley trial project is not really a part of a strategic programme unless it is regarded as the identification phase of the full e-Trolley programme.

‘Oh hell’, Anna thinks, ‘this is already giving me a headache. I’m off to find Jason.’

Jason has been patiently ploughing through emails and waiting for Anna to arrive. He knows full well that all people hate a smart-arse so he tries to keep his grin welcoming rather than know-it-all when Anna pops her head round his door. This being nearly lunchtime they head for the canteen to talk.

On the way there she brings him up to date with the developments of the day and asks where to start.

Jason says that ‘project’ and ‘programme’ are very loose concepts to most organisations. He quotes a project management expert: “All projects contain within themselves smaller component projects and are often themselves part of a larger project or programme.”

He also quotes the same expert on programmes: “projects deliver outputs, programmes deliver outcomes” and that “programme management is the orchestration of business change”.

Anna thinks Jason ought to be floating cross-legged a couple of feet above the canteen table, wearing a saffron robe and clicking finger castanets. She thinks he is like any senior management consultant: his advice is mystical and may be meaningful but is of absolutely no value to her current position.

‘Can we concentrate on the next few steps, that's all I can deal with at the moment?’

‘OK, OK’, says Jason. ‘The programme in this case is called the e-Trolley Rollout. At this early stage we suspect that the programme will contain seven projects something like this:

- a pilot to test the technology and then subject to the outcome of that pilot:

- the development of an e-Trolley

- some far reaching changes to store layouts especially around the check-out areas

- a major publicity campaign

- a staff training project for check out staff and security people

- an IT project to modify check out processes

- an IT project to modify other systems to support the new processes

Your project is project number 1 – the pilot. The board have approved the programme up to the end of project 1. In other words there is a commitment for a pilot of the e-Trolley idea but that is all. The board have put a gate at the end of the pilot at which a decision will be taken about the other projects. In a very casual way Bob has given you a programme mandate. It’s verbal at the moment but we will tie it down later.’

Jason then relates this to what the framework says about the project and programme life cycle.

‘All project and programme life cycles start with two phases called identification and definition. Normally, at the end of the identification phase a brief is presented to the sponsor who then decides whether to proceed on to the definition phase.

‘In our case, what has happened is that the board has said we should complete a pilot ‘project’, but this is effectively the identification phase of the e-Trolley programme. This is a sufficiently large and complex piece of work that we will run it as a small project.

‘Our objectives are twofold: firstly we will be testing the technology to see of the idea of an e-Trolley is achievable. Secondly, we will be judging whether the roll out of the e-Trolley programme is likely to be desirable and viable financially. These three elements, achievability, desirability and viability will form the basis of the brief and outline business case for the e-Trolley programme.

Although we are running the pilot as a project we won’t use the full method. We won’t have separate identification and definition phases for the pilot project, we’ll combine them. The pilot doesn’t need its own business case it would be good practice for us to prepare some plans for Bob’s approval before incurring a lot of costs.

Anna makes a mental note to look up the definition process in the framework as well.

She muses, ‘I expected what a lot of people call ‘best practice’ to be a set series of processes that everyone has to follow - each one a process with a variety of documents. But it seems that it’s much more about using good practice as a starting point and adapting it to each set of circumstances?’

Jason nods, ‘Pretty much. It can get very heavy handed if you try to apply it the same way on every project when you don’t need to. It can be quick and simple. You have to modify the processes to suit your own environment and the project you are running but a few simple steps do avoid a great deal of wasted effort due to misunderstandings and poor communications. There is no one single ‘best’ way of doing this’.

‘OK’, says Anna, ‘I can live with a simplified approach. So in a sense we have two phases. The first is to prepare a set of definition documentation for the pilot – that’s going to take about a month. Phase two is the actual pilot and that might take, I don’t know, 6 to 9 months.

‘Of course,’ continues Jason, who is now on a roll ‘not all programmes have the need for a pilot project but there is usually some initial investigative work and prototypes and so on before any big commitment is made. Such projects are often called discovery projects. The pilot in this case makes it more complex than usual. But if it all works out well we will be able to show a brilliant case study of how an organisation should run programmes and projects.’

In around a month therefore, Anna will present the completed definition documentation for the project and if that is accepted she will continue with the job of running the full pilot. If the technology is proven to be viable, the project will end with a brief for roll out programme and then there will be a need for a programme manager. Anna wets her lips and gets cold feet simultaneously.

They realise that some parts of the documentation are going to be either lightweight or non-existent but it is an opportunity to get the clearest possible definition of the project and its objectives at every stage. At least where it is short of fact she can say so and fill out the gaps later. Jason says that a shortage of knowledge can go into the risk register.

Bob has already outlined the benefits he expects to get from the whole e-Trolley programme and Jason gives Anna the notes Bob used in the director’s away day when they selected their overall direction. This is just background information for Anna but Jason explains that will form a major part of the report at the end of pilot.

‘It will be a matter of comparing investment, risk and benefit i.e. a business case for the programme.

Jason and Anna talk a little about the definition documentation for the pilot project and in the conversation they decide to formally name it the e-Trolley Pilot project or ETP project for short.

Jason also explains that the ETP project will deliver no benefit back to the organisation as a whole. ‘It is only a pilot – what I described as a discovery project; it is designed assess the viability of the full e-Trolley programme that will deliver benefits. It will have outputs but not benefits, or at least none I can currently see.’

They start trying to identify the objectives of the ETP project. Jason has strong views on this issue of objectives:

‘Most project managers are doomed to failure as the major stakeholders each have very different expectations. Even if the project manager fully achieves his or her own objectives and is totally satisfied with the outcome, there will nearly always be those who are dissatisfied as they expected something different. Their expectations may not have been better, bigger or even reasonable but they will almost certainly be different.

‘It therefore makes absolute sense to have the clearest possible statement at the outset of the project of the overall objectives and to get this agreed and signed off. There may still be that background feeling of dissatisfaction in many people’s minds but at least you can show how you delivered what everyone agreed you should’.

‘I’ll give you a really good example in this case. Do you think you should be seen to have failed if the organisation decides after the trial not to proceed with the e-Trolley?’

‘Hell, no’. Anna is getting ready to get angry. ‘I’m supposed to set up a trial to test the ideas. If the trial runs smoothly I will have achieved my objectives. It is not my role to make the trial a success’

‘Exactly’, says Jason,’ you must clarify what you are trying to achieve and distance yourself from the results of the trial. In fact you want to be seen to be dispassionate about the success or failure of the e-Trolley itself. See what I mean?’

Once SpentItNow becomes more mature in P3 management, they will realise that risks come in two flavours: ‘threat’ and ‘opportunity’.

For now, like many organisations they see ‘risk’ as being synonymous with ‘threat’.

Anna, calms down again and says that she certainly does and also that she realises that one strong way of defining a project is also to define what is not part of the project.

She asks, ‘What was that about a risk register, I’ve never seen one of those.

‘Well, it’s just a list of risks that gets kept up to date. It rates risks, explains who is going to look after them and how they are going to be managed.’

Risks, she comes to understand, are those things that might go wrong and that might have an impact on the outcome of the project.

Jason explains: ‘One reason for creating a list of risks is to think about the steps that can be taken to mitigate each risk. For example there is a risk that someone will break into your flat and steal all your jewellery. You recognise this risk so you take out an insurance policy to deal with it. When you plan a trip to one of the stores in mid-winter you know there is a significant risk of rain so you take an umbrella. We just need to apply this thinking to the project.

‘Of course as the project proceeds, your view of each risk will change, some will become bigger worries and some will get smaller, some will disappear altogether.

‘It doesn’t say this in the text books but I happen to think risk registers are about sharing risks. You see, if you know about a risk and keep it to yourself, you take it on your own shoulders. If you set risks down and publish them you share the risks with everyone else. It is only fair really.’

Jason notes Anna’s eyebrows meeting in a perplexed frown and realises he is not reaching her with this theoretical explanation.

‘Let’s take a simple example’.

Those eyebrows now elevate in that way she has of reacting to anything even marginally patronising, such as the word simple.

Jason hastily changes tack. ‘I mean let’s take an example from normal life. Let’s imagine we think about going on holiday together. So we discuss where to go and how to get there and what we are going to do. Let’s say we choose a winter ski holiday in Switzerland. Say you know that you have an old injury to your knee that might mean a very brief time on the piste and a much longer time limping around the bar getting piste.

‘You have a risk that the holiday might be a failure for us both but you forget to tell me about it. If your knee injury does re-occur I might reasonably say that had I known about this we could have done something different and I blame you for ruining the holiday.’

‘Very sympathetic, I must say’, says Anna.

‘Exactly. But I would be much more sympathetic if I had known about the risk and accepted it beforehand. Swap roles – let’s say it is my ankle that has a problem and you find yourself skiing alone.’

‘I’d be forced to carry on with some of those famously ugly ski instructors wouldn’t I? But I see what you mean. If I get a list of things that might go wrong on the project we can prepare for them and we collectively share them and that takes a load of my shoulders.’

Jason continues, ‘One of the best examples of risk sharing is the label on a packet of pills. If you obey all the warnings almost no one would ever take an aspirin. But if you do, and it has a bad effect on you, the manufacturer can always claim to have warned you. It’s for this reason that hotel baths carry warning notices reminding you that wet surfaces are slippery. They are nothing like as slippery as the hotel’s lawyers’.

Lunch is finished and it is time to put their trays on the conveyor that whisks their cups, plates and wrappers away to the washing up place. ‘Shall we go?’ says Anna.

Jason looks Anna straight in the eye ‘On a skiing holiday or back to work?’

‘Back to work……. for the moment.’

To break a slightly embarrassing silence Jason suggests she takes a look at the relevant pages in the framework before she goes any further. She does and finds that on non-complex projects, the framework suggests that identification and definition can be combined to avoid unnecessary bureaucracy.

She realises that her mandate, the one given to her briefly by Bob in their meeting was incomplete and that she is going to have to fill in a lot of detail before she can seek approval for her definition documentation.

After some thought, a few emails and a review of the organisation management section, they agree that Anna is not in a position to appoint a project management team yet but she can design the team. Jason says that in a mature organisation they would specify the roles or titles of the team members in case of changes but for SpendItNow they agree to cut a corner and use people’s names.

At their next chat Jason raises the concern that Bob will not really have the time to act as sponsor.

‘Can you really see our esteemed CEO attending project meetings, signing off the various documents you will need and making decisions at a project level?’ I know he needs and wants to be involved but he can only realistically maintain a high level of interest. Let’s suggest that the project needs a sponsor who can act on a more day to day basis.’

‘Fine’, says Anna, ’we’re also going to need input from IT on the computing implications, Retail Ops on shop layouts and Marketing on their side. What do we call those people: Team members, representatives…?

‘We’re not going to need them, you’re going to need them. But you’re right, the project needs people to co-ordinate the work from these specialist functional areas. It might help to give them an exalted title and to emphasise their contribution to the project. How about Technical Consultant?’

‘Well, I am going to need them to do some actual work, you know. How about Technical Manager’

‘Not bad. But remember that material about matrix organisations we used in the presentation? The work a functional group does on a project is called a work package. You, as project manager, asks each functional group to carry out a package of work and you bring these work packages together to deliver the whole project. So we can call these people work package managers. Then we can ask the relevant department heads to appoint someone to do the job.

It also means each functional department can have work package managers for each project. How’s that? I think it is about the best we can do in this organisation at its current level of maturity’

‘Fab. We will need a work package manager from IT for the computing bits – barcode readers, checkout till programmes, databases and whatever; someone from Retail for shop layouts and check-out modifications plus a representative from Marketing for the PR and publicity angle.’

‘Agreed. And if we go ahead with a weighing system built into the trolley we will need someone from Engineering to sort out the weighing devices. We won’t need any devices in this pilot but we do need to have a design for a weighing system by the end of the pilot for the recommendation.’

So the project team that Anna proposes looks like this:

Project sponsor | Required |

Project manager | Anna Key |

Project support | Jason Sherunkle |

Work package manager: IT | Required |

Work package manager: Marketing | Required |

Work package manager: Engineering | Required |

They agree over a paper cup of coffee that she will have a go at a first draft of the objectives.

Before parting Jason reminds Anna about risk: ‘You will need a risk register as a part of the brief’

Anna smiles her I-am-a-self-assured-woman smile. ‘I read an article in a project management magazine about risk management after that talk we had in the canteen’.

Jason has had a frustrating few days with the senior and middle levels of management in SpendItNow trying to create some semblance of order. ‘No worries on that account,’ he says’, there is absolutely no risk of any management round here!’

Anna tinkles a laugh before Jason goes on.

‘I think you should start a risk register, just create a short list of potential risks, their probability of occurring, the impact if they do happen and what steps you plan to take to manage those risks.’

They agree that Anna will create a list of things that can go wrong with the e-Trolley project before they meet again to discuss.

Thanks to Geoff Reiss for contributing this book