All project delivery should be executed with an appropriate level of agility. This topic develops the concept of the continuum of agility from its roots in the idea of VUCA.

VUCA is an acronym for volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity. The term was originally coined by the U.S. Army War College in the 1980s, to reflect the changing geopolitical landscape after the Cold War. It has since been widely adopted in business, education, leadership and management.

The four elements are described as:

- Volatility: The speed and scale of change that is often unexpected and unstable.

- Uncertainty: The lack of predictability and reliability of events and issues that create doubt and confusion.

- Complexity: The interconnection and interdependence of multiple factors and variables that make it difficult to understand and analyse causes and effects.

- Ambiguity: The vagueness and unclearness of the meaning and interpretation of situations that can lead to misunderstandings and miscommunication.

Projects and programmes are designed to achieve a unique set of objectives. The desirability, achievability and viability of those objectives are embodied in the business case. The greater and more innovative the extent of scope covered by the business case, the greater the chances of it being affected by VUCA factors.

In a perfect project or programme, everything would be predictable. We would have a complete understanding of the objectives and how to deliver them, leading to an accurate budget and a certain completion. But that scenario never happens because there is always some degree of uncertainty.

In project delivery, it is useful to focus on uncertainty. Volatility, complexity and ambiguity, all lead to uncertainty, and it is the level of uncertainty that is fundamental to the way we govern and manage the work.

It is also useful to think of uncertainty as being intrinsic (i.e. arising from the nature of the work) or extrinsic (i.e. arising from the world outside the boundaries of the work).

Many of the functions of project and programme management are about handling particular aspects of VUCA. For example:

- Requirements management:

- When establishing objectives, the team should be realistic about what is predictable and what is not. Predictability will not be consistent across the objectives or across the lifecycle and the approach to the project or programme should be adapted accordingly.

- Risk management:

- Whether it be the identification and mitigation of specific risk events, or a more general approach to a type of uncertainty, risk management is the essence of dealing with the unpredictable.

- Stakeholder management:

- A lot of uncertainty arises from people who are affected by or have an interest in the objectives and the work to achieve them. Stakeholder management aims to reduce the uncertainty arising from different individuals or groups.

- Just about every element of project delivery, both functions and processes, has a role to play in reducing uncertainty. But while we strive to reduce uncertainty, it can never be eliminated.

A simple analogy is walking across dangerous terrain on a bright sunny day compared with the same journey in thick fog. When the route is clear from the next step to the horizon, we can be forward-looking and progress confidently. When you can only see two or three steps ahead, you must take smaller strides and regularly review your direction.

Where there are high levels of intrinsic or extrinsic uncertainty, we need to set up governance and management in a way that enables it to proceed iteratively (i.e. in small steps) and quickly respond to changes that occur. This is what is meant by ‘agility’.

Where there are low levels of uncertainty we can afford to look further ahead and plan with more confidence. In more predictable contexts, agility is less important.

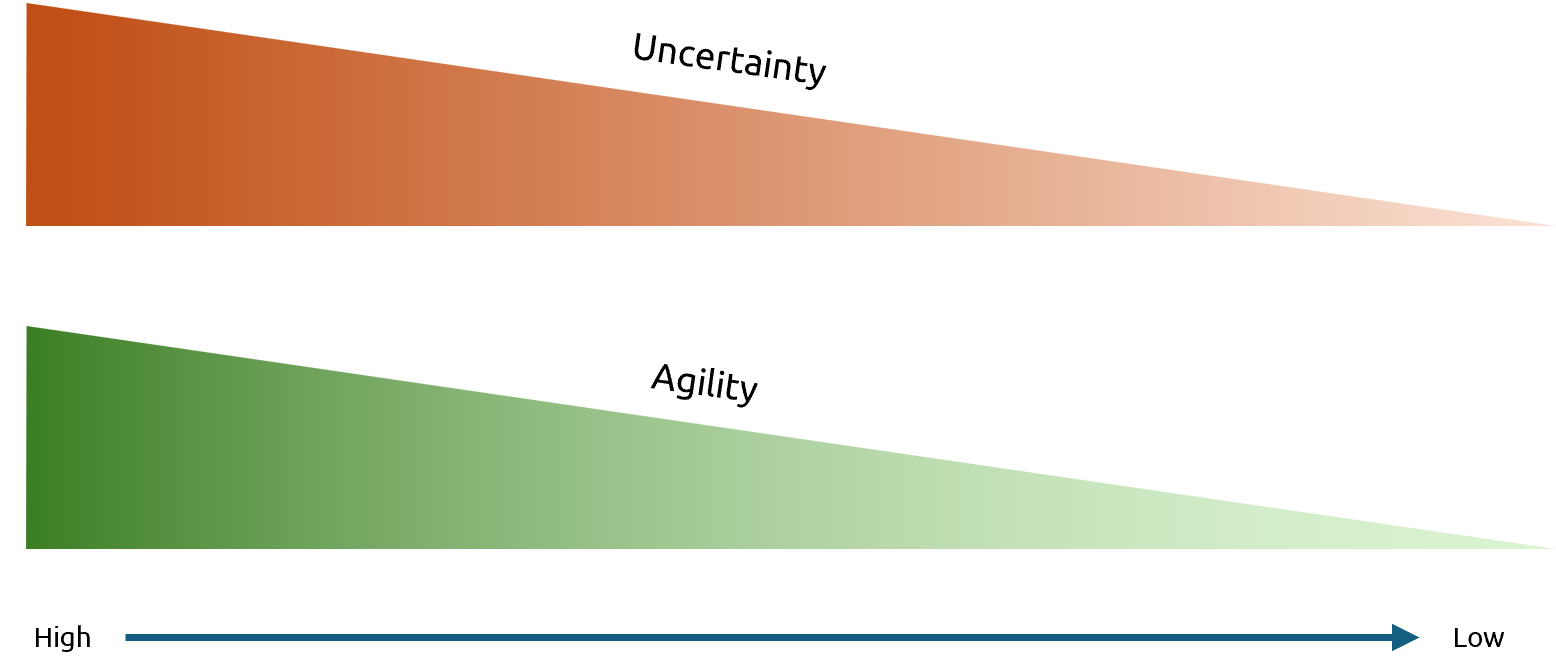

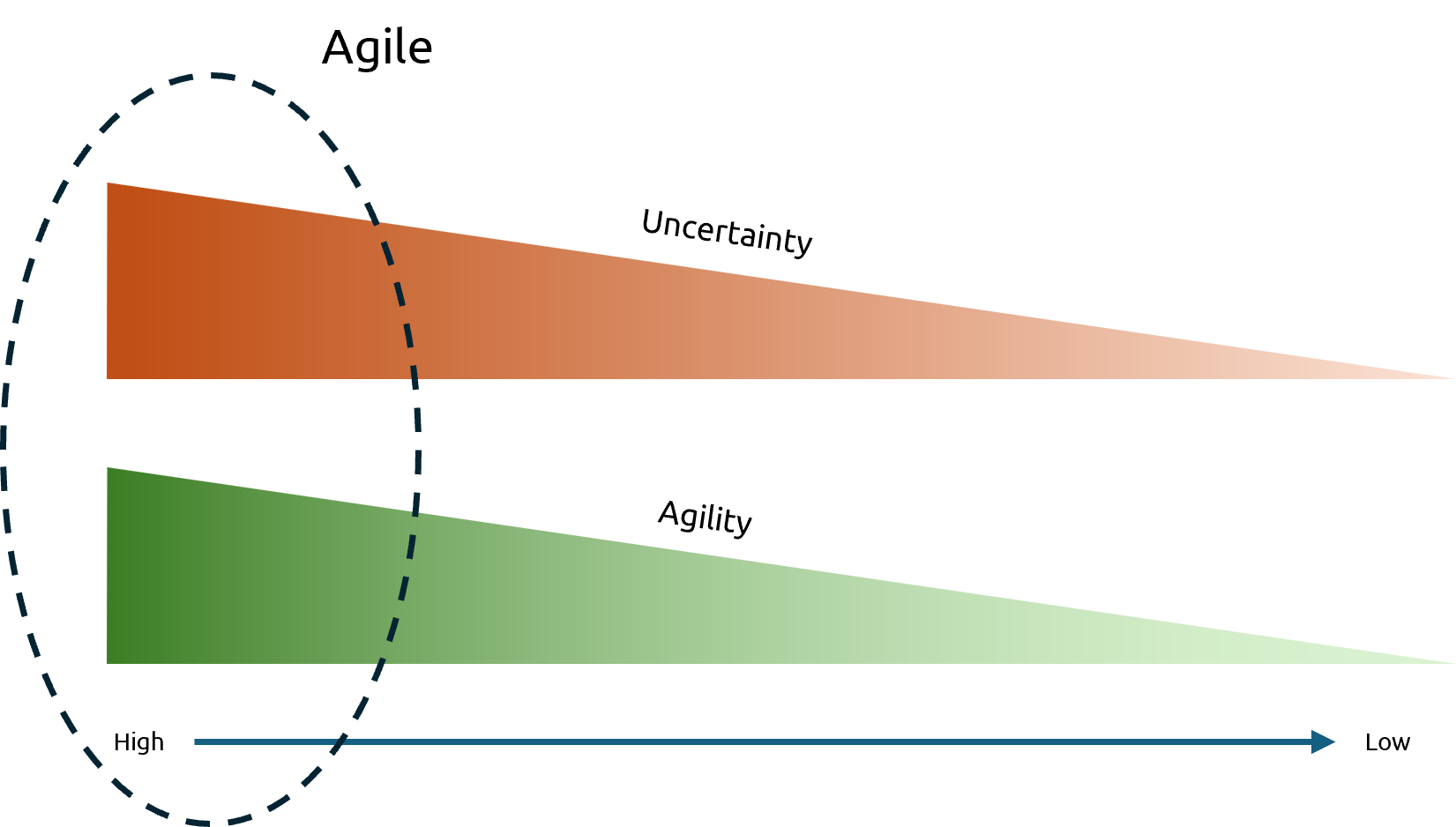

It’s clear that there is a graduated progression (continuum) of uncertainty from the highest to the lowest levels. Therefore, logic dictates that there must be a graduated progression in the way project delivery is conducted.

In Praxis, the graduated progression of governance and management approaches is referred to as ‘the continuum of agility’. The continuum of uncertainty and the continuum of agility run in parallel.

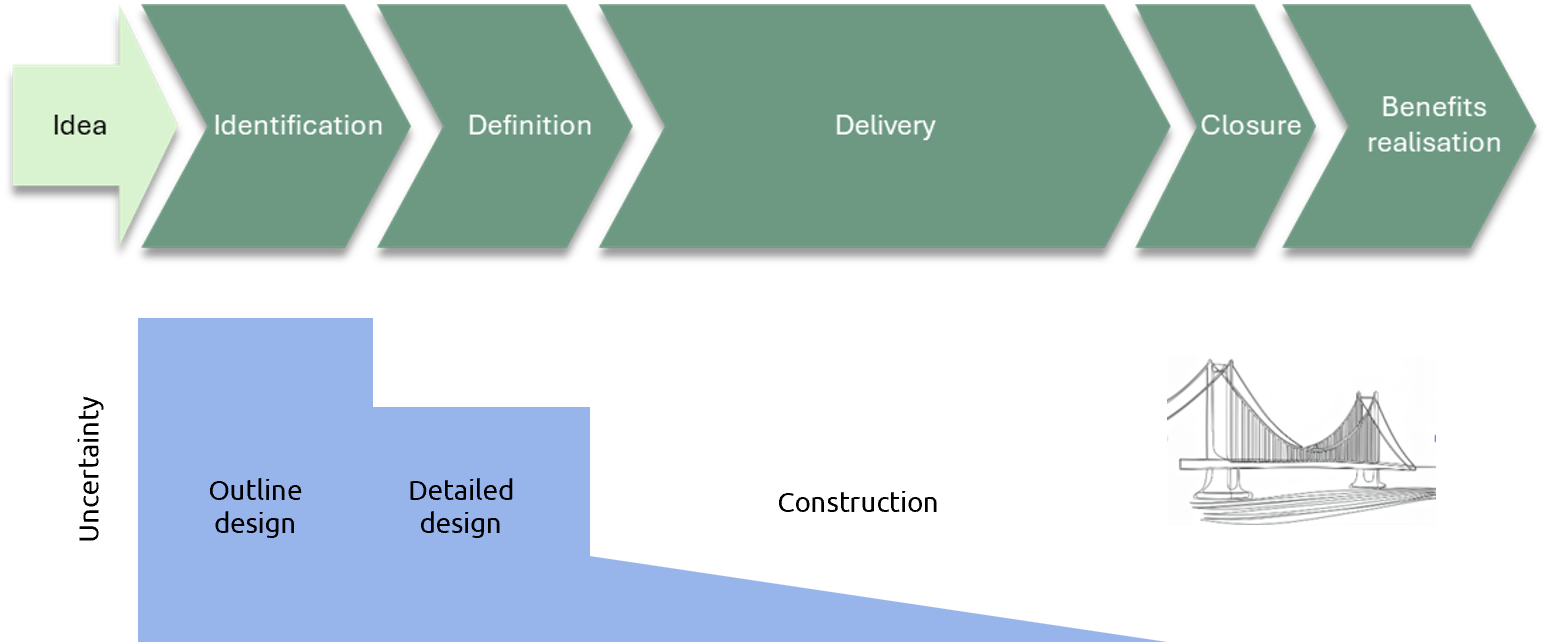

For example, when constructing a bridge, the setting is known, the purpose is clear and the location can be surveyed, the relevance and benefits of different designs are well understood, as are the properties of the materials to be used.

The construction of a bridge has low intrinsic uncertainty, but it is subject to some extrinsic uncertainty. For example, weather may affect the performance of the work and funding can be affected by economic changes.

In this situation, most of the intrinsic uncertainty is resolved early in the lifecycle.

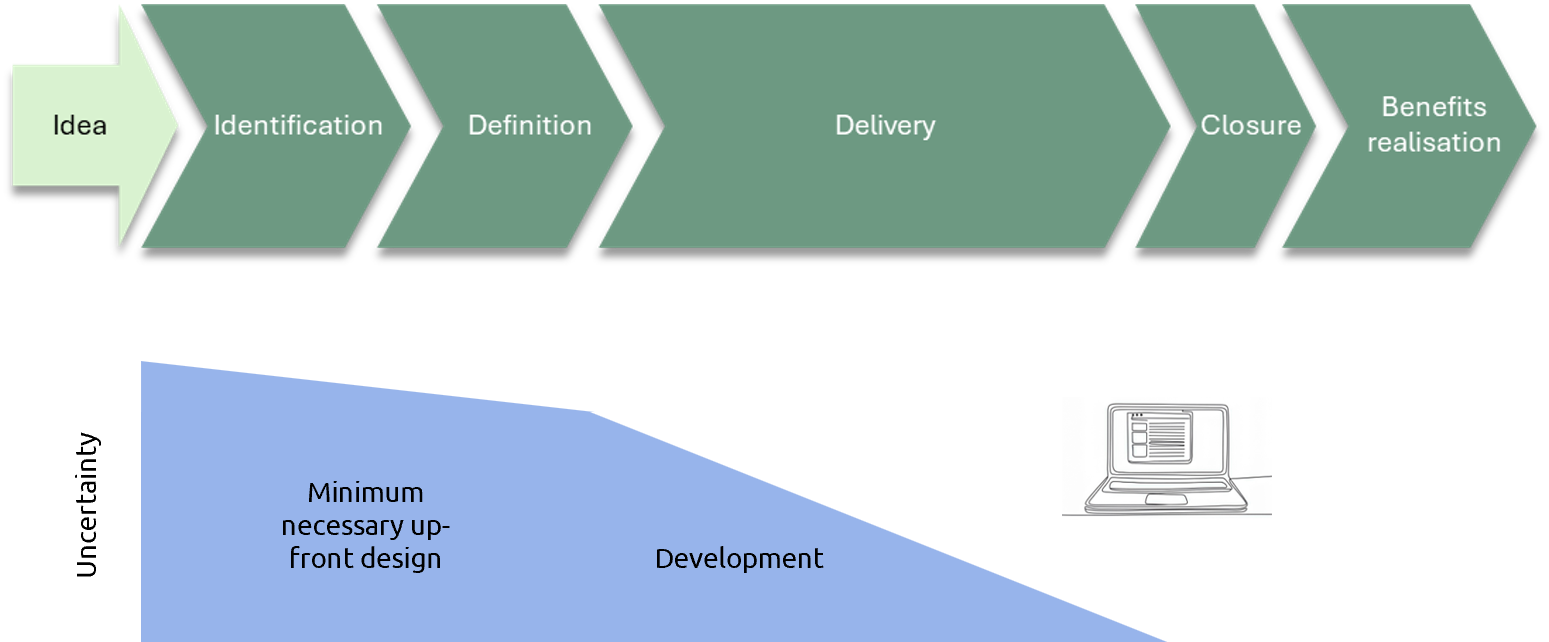

In contrast, the development of an innovative software application has a lot of intrinsic uncertainty. We may have a vision for what we want the application to achieve but there are many different ways of achieving that. Success depends upon how users will interact with the application and that is unpredictable. Technology is advancing all the time, so what seems like a good approach now, may not be so good in the future. Projects like this have high levels of intrinsic uncertainty.

In this situation, only some uncertainty can be resolved early in the lifecycle, and most will be resolved through incremental development.

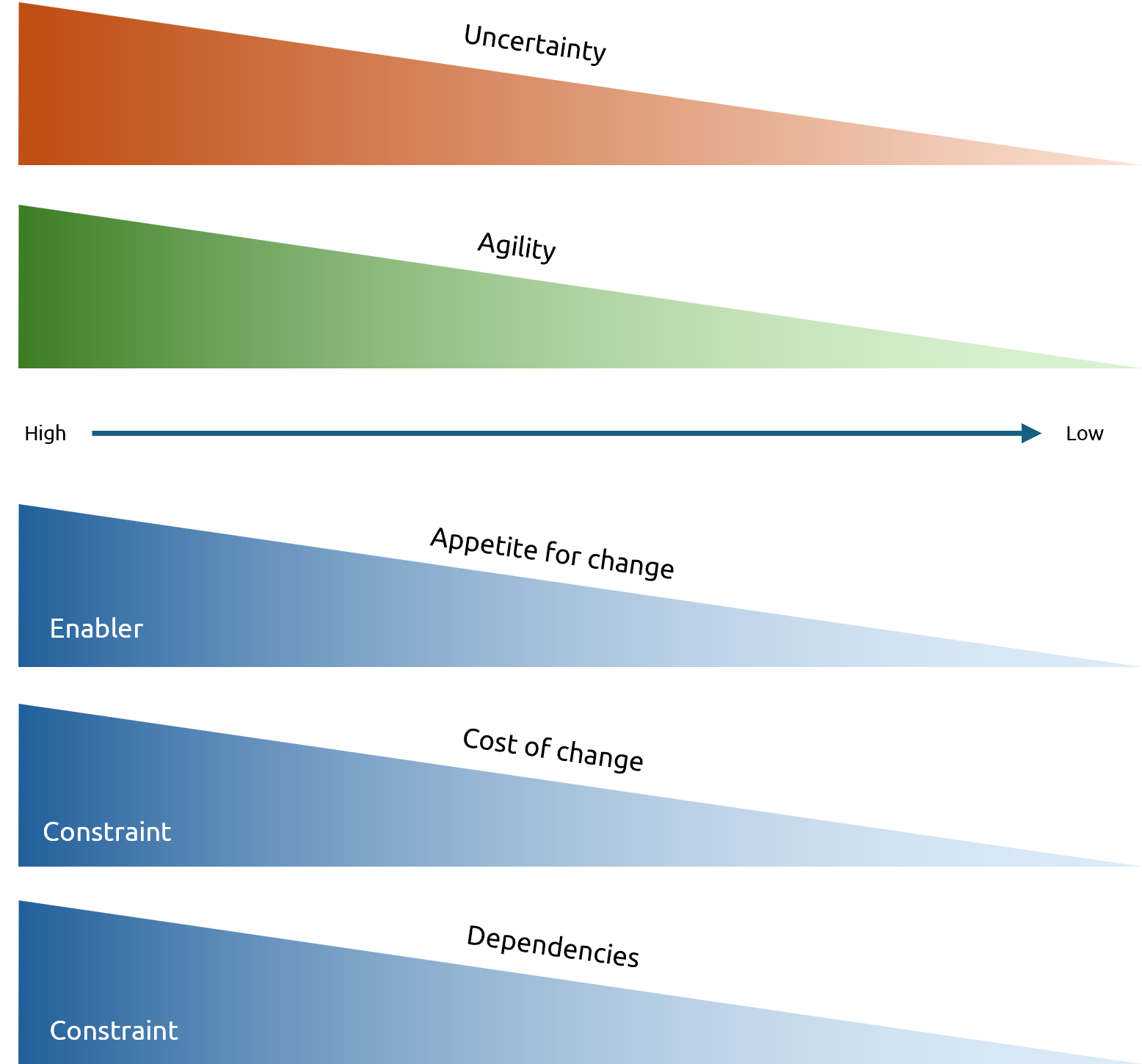

The ability to apply agility is affected by enablers and constraints.

The first factor is ‘appetite for change’. High agility needs people to be comfortable with frequent change and also needs a suitable context and external environment. When everyone involved in and affected by a project or programme have a high appetite for change, then agility is enabled.

The next factor is ‘cost of change’. If this is high, then change is less likely to be financially beneficial and the potential for agility is reduced. So high cost of change is a constraint. This is why a bridge needs to apply most of its agility in the early phases of the project. Once concrete has set, it's very expensive to make changes.

Finally, agility is associated with independent, self-managed teams. If dependencies between various elements of a project or programme are high, some level of overall coordination is needed and the ability to have self-managed teams is reduced. High levels of interdependencies are a constraint.

In the modern context of P3 management, it is easy to confuse this approach with the idea of ‘Agile’ as founded on the Agile Manifesto. Agility is a different concept that embraces all parts of the continuum. Agile is only concerned with high-end agility.

Since the Agile Manifesto was released in 2001, the range of tools and techniques available for high uncertainty/high agility work has increased greatly.

It is an initiation team’s job to identify the appropriate levels of agility, not necessarily across an entire project or programme, but for each component of the initiative.