General

The achievement of benefits in a business case often requires changes to the working practices of the host organisation. These changed practices are known as outcomes and moving from the current practice to the desired outcome is achieved through change management. Outcomes usually include a section of the organisation adopting and utilising the outputs of one or more projects.

The goals of change management are to:

- define the organisational change required to convert outputs into benefits;

- ensure the organisation is prepared to implement change;

- implement the change and embed it into organisational practice.

Organisations and individuals respond to change in many different ways. Resistance to change is a natural phenomenon and managing change in a controlled manner is essential if the benefits in a business case are to be realised.

One way of understanding how an organisation may react to change is through metaphors. Morgan identified eight metaphors that liken an organisation to, for example, machines, brains and organisms.

There are many different change management models, such as those devised by Kotter, Carnall and Lewin. Most of these can be identified as being appropriate to one or more of Morgan’s metaphors. Carnall’s model, for example, is commonly regarded as applicable to organisations that operate like a political system but not those that operate like a machine, whereas Lewin’s model is the reverse.

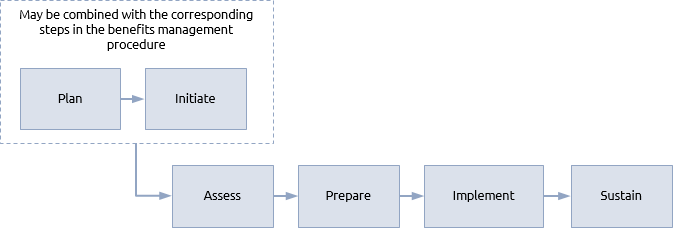

A typical, generic, change management procedure will include the following steps:

Planning produces the change management plan, which will define the principles of how organisational change should be managed. Since change is both central to the achievement of benefits and simultaneously one of the hardest things to manage well, this is a key document. It must be aligned closely to other management plans such as those for stakeholder management and risk management.

The initiation step makes sure that the resources needed to manage change are in place.

Assessment involves determining the nature of the organisation and predicting its likely response to change. Existing embedded behaviours are considered along with the organisation’s readiness and willingness to implement the required change. Ways of changing and embedding new behaviours are then determined.

Preparation involves promoting a vision and gaining support, and would normally form part of the identification process of a project or programme. This is when stakeholder management is used to gain support for the high-level business case, with particular emphasis on changes required to business-as-usual. In the definition process it would also include establishing governance and roles to support change, such as the appointment of business change managers.

Implementation is the heart of the procedure. It includes communicating and promoting the benefits of change, removing obstacles and co-ordinating the activities that transform business-as-usual from the current practices to the required outcomes. Much depends on the organisation’s readiness for change which can be represented by three key factors:

- dissatisfaction with the current situation (A)

- desirability of the proposed change (B)

- practicality of the proposed change (D)

These factors are often shown as having the following relationship:

C = (ABD) > X

C is the likely success of the change. The more the combination of A, B and D exceeds the cost of the change (X), the more likely it is to succeed.

For changes to deliver the benefits required by the business case, they have to be embedded, i.e. they must be stable and become the normal way of working. The sustain step will continue beyond the P3 life cycle to ensure that value is continually realised from the investment in the project, programme or portfolio.

Project, programmes and portfolios.

The inclusion of change management is often seen as the deciding factor in whether something should be considered as a project or a programme. Many sources claim that work including change management leading to benefits must be run as a programme. The same sources maintain that projects deliver outputs and no more.

But reality is rarely that simple. A piece of work that delivers a single output, leading to small scale change and a resultant benefit is probably best considered to be a project. Work that covers multiple outputs, complex change and numerous different benefits is undoubtedly a programme. There is no set point of distinction between the two.

A characteristic of a more complex programme is that it is not easy to predict all the necessary change at the outset. The concepts of a vision and blueprint form an essential part of the assess and prepare steps of the change management procedure with detailed change management plans evolving with the programme.

A frequent obstacle to change arises from the volume of change imposed on individuals, teams or business units from multiple sources. The programme management team should structure the tranches of the programme and co-ordinate the project schedules to ensure that change comes in manageable pieces, interspersed with ‘islands of stability’.

Benefits reviews within a programme must focus on embedding change to ensure that long-term benefits are achieved.

Standard portfolios are not normally focused on a co-ordinated set of benefits and in some circumstances may not include and change management at all (e.g. a construction company’s portfolio of client contracts).

A structured portfolio involves co-ordinating the change management plans of all component projects and programmes to ensure that they work together effectively. For example, if multiple projects and programmes are imposing change on a single business unit this can have a negative effect, either because the unit cannot accommodate that level of change or because the multiple changes conflict with each other.