General

Budgeting and cost control includes the detailed estimation of costs, the setting of agreed budgets, and control of costs against that budget. Its goals are to:

- determine the income and expenditure profiles for the work;

- develop budgets and align with funding;

- implement systems to manage income and expenditure.

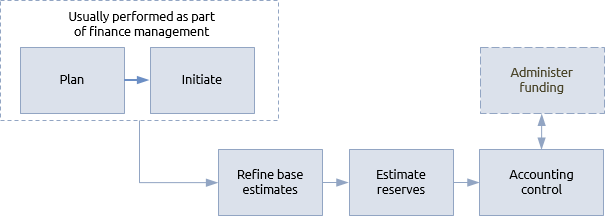

Typical steps in the budgeting and cost control procedure are shown below:

A budget identifies the planned expenditure for a project, programme or portfolio. It forms the baseline against which the actual expenditure and predicted eventual cost of the work is reported.

Initial cost estimates are based on comparative or parametric estimating techniques. These are refined as the achievability and desirability of the work are investigated and a detailed understanding of scope, schedule and resource is developed.

The base cost is the cost of the work according to the schedule. This is typically made up from costs associated with:

- resources such as staff or contractors;

- accommodation and infrastructure such as office rental or support for ICT systems;

- consumables such as power or stationery;

- expenses such as staff travel and subsistence;

- capital items such as equipment purchase.

These base costs have two pairs of possible attributes:

-

Direct and indirect: costs that are directly attributable to the project, programme or portfolio are direct costs, whereas overheads shared with other parts of the host organisation are indirect.

-

Fixed and variable: fixed costs remain the same regardless of how the work proceeds, e.g. capital costs. Variable costs fluctuate with the amount used, e.g. salaries, fees etc.

Any cost will be a combination of attributes from these pairs, e.g. variable direct costs or fixed indirect costs.

If the financial systems allow, it is useful to break costs down into a cost breakdown structure (CBS). Costs can also be classified in accordance with the work breakdown structure and organisational breakdown structure. These classifications enable costs to be reported according to any combination of cost type, resource type or section of work.

Risk management will identify the potential cost of dealing with known risk and allocate this to a contingency budget. Even the best risk management cannot foresee all possible causes of additional cost so a further level of reserve is held by the sponsor to cover unforeseen circumstances. This is known as the management reserve.

The greater the chance of unforeseen circumstances, the more management reserve is required; so highly innovative work will need a larger management reserve than routine work.

The three major components of a P3 budget are, therefore:

- the base cost estimate;

- contingency reserve;

- management reserve.

Contingency and management reserves will be owned and deployed according to policies set out in the finance management plan.

Once the costs and reserves have been approved at the end of the definition process they become the budget. The cumulative expenditure of the budget is often shown as an s-curve. This profile can be used in financing and funding. It allows a cash flow forecast to be developed, and a drawdown of funds to be agreed.

The ‘accounting control’ step of this procedure should be closely aligned with the ‘administer funding’ step of the funding procedure to ensure that funds are ready to be released to meet the costs incurred.

As the delivery process gets underway so does accounting control. Actual costs may be recorded directly by the P3 management team, or indirectly through operational finance systems. Where P3 managers are reliant upon information from operational systems, the information needs to be checked to ensure that costs have been posted correctly. Many operational financial systems are not ideal for project or programme based accounting.

Three types of costs must be tracked:

- Committed costs – these reflect confirmed orders for future provision of goods and/or services.

- Accruals – work partially or fully completed for which payment will be due (in accordance with contract terms).

- Actual costs – money that has been paid.

The forecast cost is the sum of commitments, accruals, actual expenditure and the estimated cost to complete the remaining work.

No project, programme or portfolio goes exactly according to plan. The profile of actual expenditure will inevitably be different from planned expenditure. Typically, the P3 manager is responsible for managing the base costs.

Thresholds will be set that trigger the involvement of the sponsor. These thresholds are known as tolerances and, if expenditure is predicted to exceed tolerances the manager must escalate this to the sponsor.

Dealing with increased costs may include drawing funds from either the contingency reserve or the management reserve. Alternatively, the work could be reduced in scope to cut the estimated cost to complete the work or additional funds secured. These decisions are made jointly by the manager and sponsor and highlight the importance of this working relationship.

Periodically, the business case must be formally reviewed to ensure the work is still viable. In the latter stages this review must consider sunk costs. These are actual and committed expenditure that cannot be recovered, plus any additional costs that would be incurred by cancelling contracts. Completing an overspent project or programme may be considered worthwhile if the remaining cost to complete the work is less than the eventual value.

Projects, programmes and portfolios

Just as the principles of company accounting are the same regardless of the size of the company, the principles of P3 accounting are common regardless of the scale of the project, programme or portfolio. What does change, in line with the complexity of the work, is the volume and diversity of transactions. While spreadsheet and planning software may be adequate for tracking costs on small projects, international portfolios will need to handle multiple currencies and provide different types of financial reports for many different stakeholders.

As the work becomes more complex, the application of more sophisticated cost control techniques can be justified.

The ways in which cost estimates are produced will become increasingly diverse as the work becomes more complex. These estimates are subject to the same uncertainty as all estimates and techniques used for dealing with time estimating can also be used for costs, such as applying the PERT approach. Alternatively, risk registers may include the calculation of expected value which is used in the calculation of the contingency reserve.

Where possible the procurement approach may be to transfer risk to suppliers through fixed price payment methods which reduces some of the uncertainty in the cost baseline.

Tracking costs can be combined with tracking progress in the technique called earned value management (EVM). EVM takes the budget and uses it to represent the value of the work. The value of work performed at any point during the delivery process can then be compared to the actual cost of performing it and the value of work planned to have been performed at that point. This enables predictions to be made about future performance based on actual performance to date, both for cost and schedule.

The overheads of implementing EVM can be significant and it is unlikely that this will be effective on smaller projects unless they are part of a programme or portfolio that is using the technique.

Programme and portfolio management teams must appreciate the need to balance consistency of budgeting and cost control across the component projects and programmes with the need to apply techniques that are appropriate. For example, within a portfolio, some projects may be simple and predictable, while other may be innovative and uncertain; some will have significant capital costs and others will not.

The finance management plan at programme or portfolio level should provide advice on estimating and cost control techniques while ensuring that costs reported by component projects or programmes can be meaningfully aggregated to provide comprehensive financial reporting. The prioritisation and balancing activities in the managing a portfolio process depend upon a good understanding of the costs of the component projects and programmes.

Some may see this aspect of portfolio management as being agile project management on a grand scale.

Strategic portfolios are usually aligned to corporate financial cycles. Budgets for these are less concerned with the cost of delivering a specific result, and more to do with what can be delivered within a defined budget.