General

The delivery phase of a small project may comprise only one stage; the delivery phase of a programme may comprise only one tranche. Most projects and programmes will comprise multiple stages or tranches that are conducted in serial or parallel.

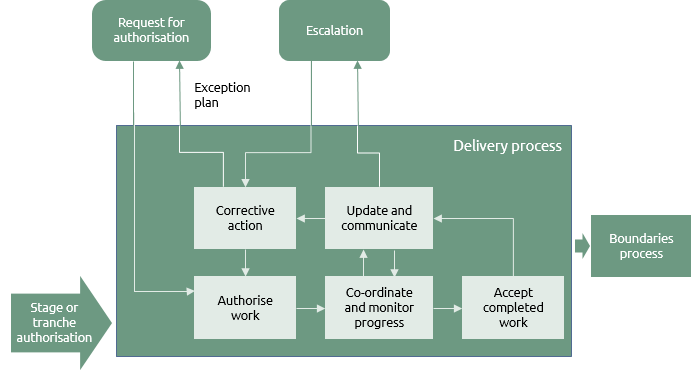

Whatever the context, managing each stage or tranche will follow a basic ‘plan, do, check, act’ cycle, sometimes known as the Shewhart cycle.

In the delivery process:

- ‘Plan’ becomes ‘authorise work’;

- ‘Do’ becomes ‘co-ordinate and monitor progress’;

- ‘Check’ becomes ‘update and communicate’;

- ‘Act’ becomes ‘corrective action’.

The goals of delivering a project or programme are then to:

- delegate responsibility for producing deliverables to the appropriate people;

- monitor the performance of the work and track against the delivery plans;

- take action where necessary to keep work in line with plans;

- escalate issues and replan if necessary;

- accept work as it is completed;

- maintain communications with all stakeholders.

The cycle will be repeated for the duration of each stage or tranche until a boundary is reached. The management team will operate the cycle within their defined authority, i.e. while the work remains within agreed tolerances. If tolerances are exceeded or are predicted to be exceeded, then issues will be escalated to the sponsor for guidance, supportive action or, in extreme cases, a decision on the continued justification of the work.

The plan, do, check, act cycle and the activities described below are shown as discrete steps in a workflow. In reality, a project or programme manager’s day will involve elements of all of these activities that are connected in ways not shown in the diagram.

Click on the components of the diagram for more detail

Authorise work

Much of the planning work will actually have been completed in the definition process (if this is the beginning of the delivery phase) or in the boundaries process (if this is the second or subsequent stage or tranche).

At this point the previous planning will need to be expanded or enacted depending upon the context. For example:

-

A stage in a smaller project may be broken down into work packages that comprise a number of products. These work packages may then be assigned to teams of internal resources.

-

A stage in a larger, more complex project may be divided into sub-projects that follow technical specialities, such as groundwork or electrical services in a building project. These sub-projects may be performed by external organisations under contractual terms with associated formal initiation.

-

In a programme tranche, the delivery will include projects and business-as-usual work. The authorise work activity at programme level could then equate, for example, to the identification process at project level. The project team will then be given a project brief from which to continue the rest of the project life cycle.

The exact nature of this activity will vary considerably according to the context of the work. However, the basic principles are the same: the stage or tranche is broken down into manageable sections which are documented and delegated to individuals, groups or suppliers.

Delegation requires that those who are being assigned the work are clear about the objectives and how the work will be co-ordinated and monitored. Clear specifications for the delegated work should be accompanied by relevant extracts from the governance documents to ensure that those managing and performing the work understand how the relationship will operate.

Back to diagram

Co-ordinate and monitor progress

On all but the smallest of projects, different individuals and teams will be working on different aspects of the project or programme at any one time. This requires co-ordination to ensure that different work packages or sub-projects within a project, or projects within a programme, can co-exist. It may be that two teams in a project need to work in a single physical space; two projects in a programme may require common, but limited resources; two work packages may impact on a common deliverable.

The management team may be able to avoid many potential conflicts in the initial planning and in the way they authorise work. However, there will always be a lot of work conducted in parallel. The greater the complexity, the more closely the work needs co-ordination from the management team. Each delivery team will provide the management team with regular progress reports but must also have clear lines of communication that allow them to escalate issues or ask for guidance at any point.

Progress information may be in the form of regular time-based progress reports or periodic event- based progress reports. The management team must consolidate these reports to understand the overall status of the project or programme. In the process of that consolidation the management team will need to feed information back to delivery teams where they may be affected by progress in other parts of the project or programme.

This activity will utilise many of the specific steps of delivery procedures such as assessing change requests, implementing risk responses, engaging with stakeholders and so on.

Depending upon the complexity of the work, the responsibility for monitoring and consolidating progress may be given to a separate support function to free time for the management and delivery teams and probably ensure greater consistency in reporting.

Back to diagram

Update and communicate

Documentation will be updated on a regular basis as specified by the relevant management plans. Some documents, such as schedules, will be very dynamic with frequent updates. Others, for example the business case, will be reviewed at significant points such as stage or tranche boundaries.

Of course, the routine update and review documentation should be supplemented by ad-hoc reviews governed by the experience and judgement of the management team. For example, if there is a significant combination of schedule, risk and financial updates that cumulatively impact the business case, the management team must not wait until the next routine review.

Progress will be routinely communicated with stakeholders in accordance with the communications plan. Where any aspect of the work exceeds, or is predicted to exceed, the agreed tolerances, then this must be escalated to the sponsor.

Back to diagram

Corrective action

Some degree of corrective action will be happening all the time. This is the essence of co-ordinating work and may be as simple as rescheduling meetings or assigning a task to another person due to illness.

This corrective action activity is about more significant action constituting a deviation from the baseline plan. The range of examples of what constitutes corrective action is vast and how it is handled is primarily down to the experience and judgement of the management team.

Two defining characteristics are:

- Which aspects of the work does the corrective action involve?

-

The action needed may relate to any or all of the fundamental P3 components in any combination. It could be very tangible in that a product has failed its quality control test (scope), material delivery is delayed (schedule) or resources have been under estimated (resource and cost). It could be less tangible where, for example, new risks have been identified that significantly increase the overall risk, or influential stakeholders have changed their position with regard to the work

It is important that the way the fundamental components of the work inter-relate is understood. How does a need to discard a product and rebuild affect the schedule; how does a change in schedule affect risks and resource availability; which stakeholders are affected and how; what are the effects of the revised schedule on the funding arrangements? – and so it goes on.

An understanding of these complex inter-relationships comes from thorough planning and maintenance of the delivery documentation. In short, if the work was inadequately planned it will be very difficult to control.

- How severe is the corrective action?

-

The first and most obvious distinction for severity comes from the tolerances set out in the management plans. When delivery plans are updated with progress they should be able to not just identify that tolerances have been exceeded but predict that tolerances may be exceeded at some point in the future.

If appropriate techniques have been defined and implemented then escalation should occur on the basis that an issue is likely rather than an issue has occurred. The corrective action is therefore something that can be discussed and agreed between the manager and sponsor through the escalation part of the process before implementation.

Even with the best planning and control procedures it is always possible that events will occur that had not been foreseen. The failure of a vital piece of equipment or the insolvency of a supplier can have an immediate and unpredictable effect. In these cases the corrective action needed may involve significant re-planning. Delivery plans may not just need to be adjusted but reworked. These are referred to as exception plans and are simply new delivery plans that show how issues will be overcome. Exception plans should be submitted to the sponsor for authorisation.

The ultimate consideration is the effect on the business case. Can the plans be reworked so that the project or programme remains justifiable? If not, the corrective action may be to prematurely close the project or programme to prevent further investment that will not generate an adequate return.

- Back to diagram

-

Accept completed work

At some point during the co-ordinate and monitor progress activity a delivery team will say to the management team “this piece of work is finished”. Depending upon the context the delivery team may have performed quality control and simply present the results as evidence that the work is complete or it may be that the management team is responsible for quality control and must now test the results of the delivery team’s efforts.

This can range from straightforward inspection of standard components to extensive testing and formal, contractual sign-off. Whether formal or informal, acceptance signifies the transfer of ownership of the work and its products from the delivery team to the management team.

Once work has been accepted delivery documentation should be updated and, if required, the acceptance should be communicated to relevant stakeholders.

Back to diagram

Projects and programmes

Small projects may simply apply the delivery process but as the complexity of the work increases it becomes necessary to break it up into manageable pieces. This decomposition takes two main forms, horizontal and vertical.

What may be called ‘horizontal’ decomposition involves splitting the delivery phase into stages or tranches. These help the management team by enabling techniques such as go/no go control and rolling wave planning.

‘Vertical’ decomposition involves delegating packages of work. This can take the form of sub-projects or work packages within a project or projects within a programme.

This decomposition requires additional processes. Where stages and tranches are created there are boundaries between them. These are managed through the boundaries process. Where work is delegated through vertical decomposition it is managed through the development process.

Back to top