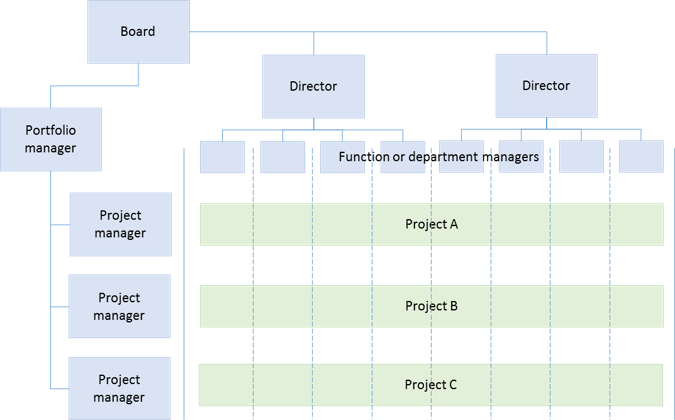

‘Let us first of all take a look at the matrix organisation in its classic forms. I’ll briefly run through the ones with which I’m familiar and try to state the advantages and disadvantages as I go’, he says whilst displaying this diagram on the screen.

‘The functional mangers or team leaders lead a team of specialised people. In our case we have functional teams in Retail, Transport, Marketing, HR and quite a number of specialist teams in IT including the database people and the teams that maintain our own applications.

‘The teams form the vertical columns in the matrix. Then the project managers have to try and get work done in each of these disciplines to deliver their projects. The project manager has to try and pull their project across the matrix where rows and columns cross. Where a specific project needs some work doing by a specific specialist team, this might be called a work package.

‘In this approach a work package is the work being done by one functional team on one project. There are a few ways in which a project manager can get a work package carried out and some are relevant to us. There doesn’t have to be consistency across all projects or departments.

‘Our first approach is delegation.

‘In this arrangement you give the project managers a budget and let them ‘buy’ work from the functional departments. Each project manager is given work to do, in the shape of projects, by the programme manager. Projects are farmed out depending on the availability of the project manager’s time, knowledge of the client or the type of work, conflicting holidays and other workload.

‘In a delegation matrix, once the project manager has been given the job he works out a budget and a project plan.

These two documents may be quite simple and he may only need to plan down to the first level - perhaps only five or ten budget items and activities.

‘The project manager then hawks the plan and budget around the various internal functional departments asking questions like ‘would you like to do the design for this job?’ or ‘How about the moulding of this new gizmo?’

‘The project manager defines the work to be done, what the inputs will be to start the work, what he expects to receive at the end of the work, the timescale, quality standards and reporting processes.

‘Informally, as he is within his own company, he is seeking quotations for executing the various stages of the work.

The functional departments essentially bid for the work. The project manager does not get involved with who actually does the work and may meet no resources face to face. He may not know when the actual work is to be done but as long as it fits within his project milestones he should be happy. The functional department manager takes away the job and come back some time later with his part of the job done. The project manager accepts the project back and passes it along to the next department.

The CFO has been listening to this intently: ‘I think this is what we actually do but we have never thought about it. How else can you progress a project?’

Anna says, ‘I do agree that some work on some projects has been done in this general way. However, I’ve been working in just such a team and it has rather been a favour that a functional team has done for a persuasive project manager. I did some work on the French opportunity and it was really nothing to do with my day job so I had no idea how important it was. I ended up doing the work in my own time.’

Jason is supportive, ‘That’s quite common. Your thinking, Anna, would have been formed by the particular project manager who was probably enthusiastic about his or her project but you didn’t have a total, rounded picture of the workload. And we will come to another approach in a few moments, I promise.’

‘The delegation approach works exceptionally well where there is more than one functional department that can compete for the work or where there are geographical distances.

Sometimes small working groups are encouraged to set up shop within the company and offer themselves to do work. Within the same organisation real money rarely changes hands. The project manager may have a budget, part of which gets transferred to the functional departments. The functional department manager has a profit target so the artificial ‘income’ from the project managers gets balanced against the only too real wage bills and invoices to calculate the profitability or budget of the functional group.

‘Sometimes this budget is expressed in man-days or Full Time Equivalents (FTE) which is the amount of time a typical employee works in a day.

‘Motivation can be a concern in a delegation matrix. The departmental heads are motivated towards making a profit just as if they were external contractors performing a sub-contract. Sometimes the interests of ‘quick and profitable’ for the functional department and 'high quality' for the project manager conflict. Also the functional managers are going to prioritise those jobs that will maximise departmental ‘profit’. Such prioritisation may not been in the best interests of the company nor in the interest of a specific project.

‘The project manager tends to be a little distant from the work in this arrangement. Even in-house, the project manager may never get to meet with and discuss the problems with the people actually working on a project. The project manager has no right to get involved with resource allocation at all. The job might be done by everyone in the department in one day or by one person over the next three months but as long as the agreed milestones and other specifications are met, the project manager should be happy. If the functional manager permits, the project manager may meet with the people working on his or her assignment.

‘Another little disadvantage of this approach is that there are no highly motivated, enthusiastic project teams - the project team does not exist.

‘However, on the plus side, the functional departments get very good at carrying out the project work that arrives from the many project managers, often rapidly and frequently. They work within their own specialist field and are surrounded by like-minded people from whom they can beg favours and give advice. The specialist departments become centres of excellence within which expertise on a specific topic is developed and maintained. People spend their lives climbing the functional ladder becoming ever more senior and expert in their jobs.

‘In some organisations the project manager can discuss their needs with contractors outside the company. The relevant internal department (if there is one) is in competition with a number of outside agencies who would be only too happy to take on some of the workload. Indeed sometimes some of the better people within the company leave and set up their own small, efficient companies to tender for work. Instead of a standard and probably friendly agreement between the project manager and the functional manager, there will be a need for a formal contract but the principle holds firm.’

Anna asks, ‘What happens if a department’s work is delayed? ‘

Jason replies, ‘As long as those delays stay within the agreed milestone plan there is no problem and no delay to the project. But, life being what it is, the delays will probably mean that some resources are engaged for a longer period than expected and therefore they will not finish the work on time nor be free for their next job. As soon as a functional department realises it is going to miss a deadline it should tell the project manager who should tell the other departments down the line about the delays.

‘The project manager has every reason to be honest. But often the functional departments don’t realise or won’t admit that they are going to be late until it is too late to correct the situation and then the group or work package next-in-line gets upset at being let down. The person doing the letting down is the poor old project manager who has go to the next department and tell them something like, err, for example, that as the design for the new product is not ready, the prototype assembly work cannot begin on schedule.

‘In a competitive world you can guess which design manager is going to the bottom of this project manager’s list for the next job.’

One of the mangers contributes a thought, ‘In a non-competitive world bottom of the list equals top of the list as there is only one name on the list – isn’t that where we are?’

‘Yes’, says Jason, ‘but let's take a look from the departmental manager's perspective, and by the way these people are sometimes known as Functional Managers.

‘Departmental managers can help by planning their work. From their perspective they have many project managers who bring them work and they have to try to satisfy them all. Each project manager, each job, starts as just two milestones: a start and a finish. Start means the start of this department’s role in this project and finish means the end of this department’s contribution.

‘The departmental manager looks at the sort of work involved and, knowing the people under his control, decides who is going to do what and when. He assigns individuals to do the work.

‘The departmental manager does this kind of thing by balancing an individual’s strengths and weaknesses against the urgency of the job, their holidays and training plans and the non-project work that must never be forgotten. The plan starts off with a list of unconnected jobs, gets broken down into small sub-projects and then gets extended with resource allocations.

‘At this level the functional department might be scheduling work with simple spreadsheets.

‘That is all I wanted to say about the delegation process. Let’s move on to the Full time assignment matrix sometimes known as loan or secondment.

‘This is another approach and a much more personal one at that. The project manager is once again given the job to do and approaches the functional managers but this time asks to borrow staff. Conversations start like this; ‘I’m going to run the dam project in Malaysia and I need a concrete technologist, 40 carpenters and some good luck.’

‘The functional manager thinks about this and assigns a concrete technologist person to the project manager for the duration. How the roles are changed! Instead of doing the job for the project manager like a contractor, the functional department is lending out bodies like a temporary staff agency.

‘The project manager is building a team of people on loan to the job from the various specialist departments and the team will set about this project as one united group. The project manager must clearly plan in detail enough to predict his demand for resources of all kinds. His budget will be hard hit if he has carpenters and concrete technologists sitting about on his dam project waiting for some dam thing to do.

‘Now we are typically talking about quite large projects where a team of specialists are working full time for the duration of their time on the project. Very often the person on loan moves from the head office to a project office. The project manager builds his team and tries his best to weld them together to work together and achieve the project. This is what happens every day in construction and heavy engineering work all over the world. The functional manager’s job is to have the right sort of people just about to come free when they are needed.

‘The ideal departmental or functional manager should run a tight department where people move from project to project or business-as-usual with a minimum of breaks. The functional or departmental manager would provide advice to their staff members about their careers, their training and what will be good for them do. The functional manager hires in new people, bids a fond farewell to good people that leave and breathes a sigh of relief when not so good ones go. The functional team may have their own workload of on-going business-as-usual work to balance against the demands of the many projects. Whilst there is a pool of expertise in such organisational structures, it tends to be spread around the place, country or even world.

‘Departmental managers may therefore organise ‘knowledge exchanges’ (sometimes known as communities of practice) bringing together, for example, all the concrete technologists from the various projects in hand around the globe as well as the technicians in head office. At these events the company’s total experience in a topic is collected in one room so they can swap ideas and experiences. Our man in Malaysia might give a lecture to his follow specialists about the special problems of laying concrete in tropical conditions. Perhaps someone else is working in the office on a different but equally interesting technical problem.

‘The department head keeps in touch with the many project managers and especially when one of her specialists is likely to becoming free off a job. She must find something to convert the unemployed resource into an employed resource - ideally another job. Her role is to balance having people ready to drop onto new projects with a low running cost and the performance of the on-going non-project workload.

‘The project manager is rather well off – there is a full time team who are likely to become quite excited and motivated about the project as they live, eat and breathe it every day. Not for them the diverting and disconcerting life working on forty two projects with as many managers.’

One of the senior managers at the event has had a team on loan for some time and remembers something that made him sore.

‘The problem I had when I tried this was that every resource has two bosses, two lines of authority. Somehow the project manager and functional manager must manage the resources between them. Clearly, the long term future and career path of an individual should lie with the functional manager as he or she has a long term perspective on the person’s future. The project manager can say, at any time that he no longer needs the loaned resources and pass them back to the functional manager.

‘Equally what happens if the resource is a poor timekeeper or fails to perform in some other way? Who issues the formal warnings? I have had problems and issues that need addressing in this two-boss environment.’

Jason agrees this is a real problem but only where the person is shared between two managers at one time. In the part time assignment matrix the resources are grouped into functional areas and loaned out to the project teams as before. The demands that the project make on each person’s time are such that they are required only on a part time basis.

‘Of course this part time loaning is much more common in businesses that involve technology like our own.

‘The effect is that each person has a number of ‘pulls’ on their time. The demands of many projects add to the many normal demands of the functional department and these all pull resources in many directions at the same time. This is because there are many, rapidly changing priorities on each activity and those priorities are set be different people.

‘The result is often that each resource is frequently or even most of the time, on the start-up curve. They frequently find themselves having to pick up a job, gain or refresh their understanding of the requirement and start work. As they begin to ‘get into’ the activity they climb the learning curve and become efficient at performing the work.

‘Just as they reach, or sometimes before they can reach, a level of efficiency the resource’s priorities are changed again by a manager and the resources is persuaded or told to drop the current job and start on another.

‘Of course some managers do this with their own full time staff but the problem is much worse in a multi-project, multi-department environment.

‘These problems can lead to low morale as the resources feel that whatever they do they will be unsuccessful and continually let people down’.

Jason ends his monologue: ‘Having said that, this is the most common system of all and one we will most likely use, we just need to be prepared for it.’

Jason pauses and sips his water. ‘The next arrangement is the ‘resource pool’ – something that is quite popular in many organisations.

‘In the resource pool system resources, perhaps of mixed specialisms, are collected in one or more resource pools and loaned out from that pool to the project teams.

‘There may be one pool for each type of resource – network people, cabling people, Windows experts. Or, in a smaller organisation just one pool containing all resources.

‘All of the problems mentioned above in the secondment or loan approaches still occur except that there is no background departmental workload. It is necessary to develop some strategy to decide on prioritisation – a method of deciding which resources should spend what time on each project. This can be a committee of project managers or it can be a ‘resource pool manager’.

It is possible in a pool system for resources to lead a very quiet and undemanding existence without doing very much work as there is no direct manager responsible for each resources overall time. A time recording system that is used to record time spent in such a way that ensures project managers’ approval reduces this danger.

‘The resource pool is different to the functional team in that it exists solely to loan people out to other teams especially project teams. The resource pool has no business as usual apart from personal development issues like training and experience sharing.

‘The resource pool manager’s objective is to have all of his people fully utilised by the project teams and to have no one ‘on the shelf’. The resource pool manager has no business as usual workload. The pool manager also makes sure no one drowns.’

Jason notes which people look up in surprise, who smiles and the others who take this as it comes until they realise something is going on. He likes to keep his delegates awake.

He goes on. ‘A resource pool is a special case of the specialist team. The pool will represent a group of people covering a certain range of specialist skills. People in the pool will have a career and try to progress from junior prawn sexer to the dizzy heights of senior prawn sexer and eventually to consultant status.

‘There will be a team leader who manages the team and tries to help the team share knowledge and experience.

‘OK then’, pipes up a senior manager, ‘what’s the difference, or just the key difference between a resource pool and a functional department?

Jason looks at Anna who looks back with eyes seeking help. He is ready.

‘Specialist teams contribute to projects either by:

A - accepting and performing work packages that form part of a project

B - loaning their team members to form project teams

Resource pools only have option B available.

Also resource pools have no business as usual workload, apart that is from keeping up to date with their technology.

‘Resource pools are in the business of loaning people out to project teams and tend to be found where there is a fairly consistent project workload. If all of the resource pool members are loaned out to project teams and performing useful functions….hang on, let’s not be too unrealistic: if all of the resource pool members are loaned out to project teams and being charged to those projects, then the resource pool manager is probably meeting their objectives.

‘I know of an architectural design practice – a specialist architectural practice who might well have designed your local leisure centre – that operates a resource pool containing architects, drafting people and other specialists.

‘They have a number of design projects on the go at any one time and these design projects combine the input from a rage of specialists. Jason actually said ‘range’ but his notes said ‘rage’. One of the managers, a thin lady wearing severe glasses and tightly pulled back hair asks what the collective noun for specialists ought to be. This little diversion is rather surprising for this lady but Jason and Anna let them list such words as a pride, a school and the eventual winner: a shortage. Anna and Jason glance at each other agreeing that a light moment is fine at this stage.

‘So when someone awards the architectural practice a new project the pool manager appoints a project manager from the pool and said PM sets off to evaluate the project and prepare a plan for the design activities.

On the basis of the plan the PM and the resource pool manager decide what resource will be made available to the project team and loan those resources from the pool the project. The PM then ‘owns’ the people and has a project team to work with.

Some people are loaned full time and others on a part time basis.

The assembled group of SpendItNow managers and executives discuss the advantages and the problems people encounter when setting up these schemes.

They realise that many organisations actually operate a range of such processes. Some projects are made up from loaned project team members and yet delegate some specific work to specialist departments.

Jason summarises the differences between delegation and loan.

| Delegation | Loan |

|---|---|

The functional team leader instructs and receives updates from team members. The project manager plans at the work package level. |

Project Manager instructs and receives updates from team members. Resource pool managers loan staff to projects. |

They all agree that most organisations give little or no thought to these matters, Jason argues that this lack of understanding is a major cause of project failure. Resources are unclear of their work and less of their priorities.

People are dragged from job to job in a very demoralising and depressing way. Some try to work very long hours to meet the many demands of their many managers and some do very poor work with the same objective. Very many projects get delayed and these delays cause future work priorities to change and cause similar problems later on.

This rapidly becomes a downward spiral from which it is very hard to recover.

They make a number of decisions about the way the organisation should work and needs to work, and decide to take these decisions to Bob and the rest of the board in a written report.

After the away day they do continue the work and eventually complete a report in a state ready for the board. To do so they have to ignore the rules they themselves are writing as they have no agreement to do this work nor any way of recording the time spent.

The board decide not to act quite yet but to test the whole approach as far as possible on the e-Trolley project. Jason to a larger degree worries about how you can test a whole organisational system on one single project.

However, it’s agreed that most of Anna’s project will be based on loaned resources and all the people on her project will be very firmly requested to complete regular and timely timesheets. She will delegate the IT component to the IT department who will set up their own project manager to manage the work packages that will make up IT’s contribution to the e-Trolley project.

Jason is pleased that he will be working with Anna on this project but realises that no one has yet told her of her good fortune – her project is to be a test of the e-Trolley ideas but it will also to be a test of the company’s new framework for project and programme management.

Thanks to Geoff Reiss for contributing this book