Bob likes away-days where everyone is out of the office, out of reach and un-distracted. If he could he would take them all to bathe collectively, like that that scene in the Blues Brothers movie where all the characters appear out of the steam in a Turkish bath. As his own bathroom is a little small for major conferences, he dreams of a Turkish or Roman bath where at least his creativity could flow freely. He knows this is slightly on the impractical side of impossible.

At a local conference centre they drink too much coffee, eat too many croissants and discuss the issues of investment and projects. They spend a little time wondering why it is that you only ever find bottles of Rose’s Lime Juice and little white mints on conference tables and decide to check their own sales levels of the lip-puckering drink that is so ideal for people giving speeches.

Bob, with the firm backing of the CFO, convinces them with very logical arguments that there is a strong case for a proper project selection process. This causes some disquiet amongst those who will now have to defend their pet projects against an oncoming tide of financially backed logic.

They decide to set up a selection process and Bob asks for, and is authorised to bring in, a major consultancy to sort things out.

Back home over dinner Bob tells his wife Anthea about the effect their idea has had on the company and what he now plans to do. Anthea mentions Jason: ‘Your nephew Jason does something in that area doesn’t he? Are you going to open some wine? Jason will be at the party next Sunday. Are those Mange-tout done?’

Bob has learned that whilst much of Anthea’s verbal cascade is totally rhetorical, it often contains an absolute gem. He runs over the dialogue in his mind searching for the bright, gleaming bit. Jason, Wine, Mange-tout, Party!

‘Party! What party?’ he asks.

‘You know – we are going to your brother’s for their anniversary next Sunday’, says Anthea. ‘We leave mid-morning and arrive in time for a light lunch. Jason’s sure to be there.’

Bob is forced to reluctantly re-arrange his morning bathe on the following Sunday but does get to meet Jason at the family do, talks to him about the problem he has at work and the processes he thinks he needs. Jason lays out a few options and seems to know his stuff about the topic. Jason says that portfolio management is the correct term.

Some other family members wonder what Bob and Jason are so engrossed in and inevitably this starts rumours.

After a little of Bob’s persuasion, Jason takes a day off from his job with a major consultancy and come to speak to the other SpendItNow directors about portfolio management.

Jason’s face and build is much softer than Bob’s, the result of Bob’s elder brother whose appearance gives away his Ukrainian upbringing but who married a French beauty when Bob was a teenager. Jason has an odd mixture of French chic and Ukrainian firmness. He has a slight, elegant build but the strong face of his Eastern European ancestors. Many women find this mixture of deep, dark set eyes and slim elegant body very attractive.

Bob organises another away day with all the SpendItNow directors to talk about best practice in portfolio management with Jason as their visiting expert. Jason takes almost all of the content of his PowerPoint slide presentation from a source he knows about and is sure his audience will be ignorant of the Praxis framework.

Jason stands alongside the slightly wobbly projector screen where his first PowerPoint slide is displayed.

The slide defines the major terms in P3M. Jason needs to get the board thinking about the topic and warms them up with some definitions that he has adapted from the Praxis web site.

Jason emphasises that these are very simple explanations and that the group needs to think about their own context and what they want to achieve.

‘Ultimately, it’s all about thinking strategically and realising benefits. These could be financial or non-financial. Financial benefits include reducing the cost of, or increasing the income from an operation. Sometimes, and especially in the public sector benefits may be in terms of improving levels of service or image’.

He finishes the slide having described what a portfolio is and explains: ‘Once strategic objectives are established, the organisation can identify projects and programmes that help attain them and think carefully about the benefits they are designed to bring about.

Having worked with companies like this numerous times before, Jason knows that he needs to get the board to understand that they have a portfolio of projects and programmes and they need a structured approach.

With a click of his mouse Jason throws up a new slide on the slightly wobbly screen.

One of the directors is already looking rather cynical about this ‘load of management twaddle’. Jason quietly explains that, in his experience, many large and successful companies use this approach for managing projects and programmes.

Some of the others are just a tad less cynical and are sitting upright and taking obvious interest. Others are looking downright scared or simply half-asleep

The Chief Financial Officer has long been convinced that SpendItNow is roughly as good at selecting beneficial projects as a dead rat. He asks for real life examples of what portfolios look like.

Jason explains that they look different in different contexts.

‘For example, many organisations use the term portfolio for a group of projects that simply benefit from a consolidated approach, maximising the way resources are utilised.

‘Jobbing engineering companies, software houses contracting for work, architectural practices and many other types of organisation run many simultaneous projects each of which results in the delivery of a separate product to a customer.

‘The common elements of the projects are that they run simultaneously or at least overlap with each other, they share resources and are supposed to generate some income.

‘Praxis calls this a standard portfolio’.

Various directors point out that this does not relate to SpendItNow. They do however agree that their organisation does have a strategic vision for the future and that all projects and programmes should help to deliver that vision.

‘That’, explains Jason ‘is a structured portfolio.’

‘Hang on a moment’ says the CFO, who is still trying hard to shake off the image of a dead rat that has become lodged firmly in his mind, ‘we’ve been spending money on project management training and consultants for years.

How is this different?’

Jason explains that until now, SpendItNow has been focused on managing individual projects and hasn’t addressed the big picture. ‘It’s important to manage projects well but it’s even more important to do the right projects’.

The CFO supportively comments that a structured and organised way has got to be a good thing. ‘The expense of carefully selecting our projects and programmes would be tiny in comparison with the investments we make’, he says.

Jason takes the view that SpendItNow is a classic example of an organisation that would benefit from a formal portfolio management process.

‘From what I understand, the company carries out a whole range of projects and programmes. Every single one of them is designed to bring about a change, or perhaps we should say improvement to the business’, he says. ‘You don’t do projects because the organisation is paid to do them; they are designed to change the company for the better. Could one of you outline a recent project or programme and the benefit it delivered please?’

This apparently innocuous question causes the directors to do a great deal of staring down at their notes, the tablecloth and through the window thoughtfully. No one looks anyway near the space currently occupied by Jason.

The simple and rather worrying truth is something no one wants to acknowledge and few are prepared to admit: if the recent projects were conceived and designed to deliver change then that original objective has been lost in the mists of time. And that ‘if’ is so big it ought to be in capitals as many projects had the key objectives of satisfying a whim whilst keeping everyone employed and looking busy.

The IT Director was just about to offer the project to switch over to Windows 10 and Oracle databases for discussion. Then he remembered that it had absorbed many IT resources for an amazingly long period of time and caused a number of temporary contractors to be hired in, many of whom have stayed on drawing their enormous day rates and happily working on something or other. He also recalled the desperate but largely unsuccessful effort of trying to explain to Bob how this had actually helped the company.

The Human Resources Director thought of the management training programme that had gone well and been welcomed but quickly realised that he had no idea what the resultant benefit of it had been.

Only Bob’s number one fan, the CFO, offered a thought after waiting a suitable period and after a meaningful glance at Bob. By this time everyone had realised they had nothing to be proud of in this area.

‘Jason’, he asks, ‘Sixteen years ago we spent a fortune on that Year 2000 bug thing and we are still here in business. Our world didn’t collapse that night. Does that count?’

Once the very relieved laughter dies down Jason says that it certainly does.

‘There are certain projects that an organisation must undertake just to stay in business and these are the highest priority projects of all. For example, you have to react to legislative changes because, if you don’t, you’re dead in the water and out the game, belly up. Right?’

Various uncertain nods greet this mad mixture of metaphors.

He presses on: ‘Didn’t you introduce a loyalty card a little while ago. What was the effect of that?’

The Retail Director feels many eyes looking at him and feels pressed to speak.

‘Yes’, he says slowly picking his words with more care than a criminal in the dock, ‘we did do that’. He searches his memory for help. Nothing much emerges as his memory seems to focus on the fire escape he noticed in the corridor outside of the room. But, in the nick of time, inspiration arrives via another route: ‘Our competition were starting to offer deals and discounts and points and air miles and other incentives so we thought we had better keep up with them to maintain our competitiveness’.

Jason asks the room as a whole: ‘Do we know how much the loyalty card cost to get off the ground?’

Now it is the CFO’s turn to slowly pick his words but not for reasons of uncertainty about his knowledge. He is uncertain about the impact his response will have but it was not his responsibility so he thinks ‘what the heck’.

‘I don’t think we do. We did have a marketing team working on the card design, in-store promotions and the discounts and gifts we gave away. I recall approving a budget for this. Part of this team was made up from our own people so they didn’t cost much but some were hired-in specialists and boy, did they know how to write an invoice.

We did some staff training at the stores to get them ready. And we did an IT project to control the cards and to track all the loyalty point count information so customers’ claims could be checked. But how much time and money went into it is something I don’t know – it got lost amongst the Marketing and IT budgets’.

Jason picks up on something the CFO just said: ‘You said your own team didn’t cost much. Let’s be careful here – one of your major costs in any project will be the cost of your own people. Surely those people are well paid and would be doing something useful elsewhere if not part of the project team. Never overlook the cost of your own people.’

And so it became clear to the board of directors of SpendItNow that not only were the benefits of their projects unclear, not only was there a complete lack of a system to predict costs but there was no system to work out how much a project had cost after it had ended. Jason started to see this company as a relatively green-field site. He knew what any successful consultant knows: the worse the start point the easier it is to impress.

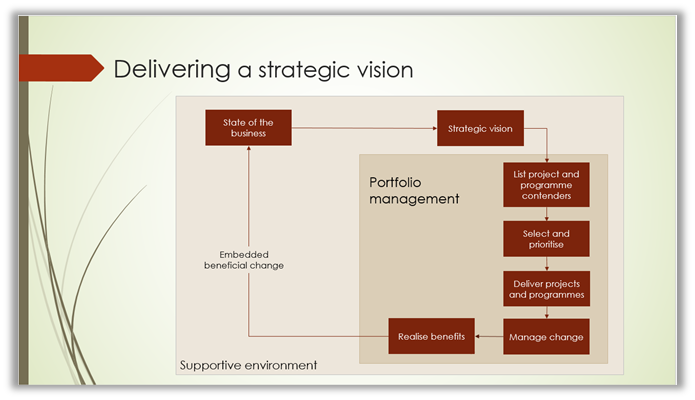

Having rather given up on the activity of trying to find a project from the recent past that has shown any form of measurable improvement to the organisation, they move through a discussion about the current project workload and Jason displays a slide showing how the overall vision leads to a portfolio of programmes and projects that eventually implement change and deliver benefits.

They take a break for tea and some collective reinforcement before reconvening in their seats. Magically the staff at the conference centre have found yet more Lime Juice and little peppermint sweets.

When they restart Jason explains that in this process the organisation defines its current reality and its visions for its future. Where it is now and where it wants to be. There will be many mixtures and combinations of programmes and projects that might be able to deliver that future and many projects that the members of the organisation want to do for a variety of other reasons, some valid and some less so. These are listed by the portfolio management team and then whittled down to a selected few.

You can download all Jason’s Powerpoint presentations here to use as you see fit – don’t worry, he’ll never know.

‘They must all be aligned with the organisation’s strategy’, reminds Jason who calls these Contender projects and programmes.

He states that most organisations take on far too many and deliver too few. He tells the tale, well known in professional circles, of a very successful consultant working for a major bank.

On his arrival the bank had 150 projects and of these around 40 ended with some degree of success. One of his major contributions was to establish a resource availability constraint where he kept a watchful eye on the organisation’s ability to deliver change. In the next year they started only 50 projects and delivered on all of them. He therefore dramatically reduced costs and delivered more. Hardly rocket science but very, very worthwhile and much appreciated by the board of directors.

SpendItNow will be unable to deliver all of these contender projects and programmes as they all demand resources of both people and cash, and the combined demand will normally outstrip availability by some distance.

Once the best projects and programmes are selected, the managers run them to deliver benefits back to the business users. This leads to a new reality, a new and improved organisation.

Jason says: ’I’m making this sound like an annual process of portfolio management and for some organisations it is exactly that. But for many, and probably for your company, it is a continuing, on-going process of identifying and prioritising existing projects and new possibilities, perhaps resulting in a quarterly strategy review. In some organisations, where the outside environment has a major effect, this process can mean canning projects well into their life cycles and deep in their budgets.

The CFO bristles: ‘I don’t like the idea of canning projects where we have already spent loads of money just because it rains’. Everyone laughs and glances out of a window.

Jason explains that the ‘outside environment’ refers to what your competitors are doing, legislation and a whole range of marketplace driven effects on a project’s business case.

He says, ‘This can work both ways. If you were developing a production process to produce a particular product line and there was a major health scare likely to seriously damage your sales prediction, you might can the project.’ If on the other hand a major competitor withdrew or simply went out of business at a convenient moment your new product might succeed beyond your wildest dreams despite the development project having gone over budget and way behind schedule.

‘The key point here is success is measured in terms of the effect on the business and not in terms of the delivery of the new system’.

Jason clambers up onto a hobby horse and from this lofty position starts to jab his finger towards his audience. ‘I think there is a very macho thing in most organisations about delivering projects on time whereas time is often quite low down the list of important factors.

For example, delivering a new IT system a month late may be unimportant in the context of a five year payback period. (The IT Director, famous for late delivery, at this point starts to relax for the first time on this away day). It is the benefit that counts above all. Now the late delivery of a project or programme may easily reduce the benefits but I think most organisations focus on time simply because it is so easy to measure. It’s the benefit that counts every time.’ The IT Director tenses up again.

Whilst excitedly delivering this speech and jabbing his finger at the audience Jason has nudged the wobbly screen with his elbow. His audience is slightly taken aback by the ferocity of his delivery so he backs off.

He quietly states, ‘Thus portfolio management is a never-ending cycle of improvement.’

After a short respite and a look back at the slide still displayed on the quaking screen, Jason also says: ‘The whole process must take place within a supportive environment where everyone understands the strategic vision and the route to that vision.’

To clarify this he uses as an example of one of his previous clients. This organisation had a strategic vision of being the leading player in their market. This was their main objective. They tried to set up projects and programmes to improve quality control, customer care and service delivery. It is not really very important but they happened to be an airline with a fleet of airplanes to maintain, ticket sales offices to manage and operational services which included flight crew and IT.

Each of these divisions of the company set up their own projects and programmes in line with the overall objective but focusing on their own sphere. They were pretty lucky to have discreet divisions so there were virtually no cross-functional programmes.

‘What’s so bad about cross functional programmes, Jason?’ This comes from the CFO.

‘Well, they are notoriously difficult to manage in larger organisations as they typically need authority to be spread across areas where authority is rarely shared. I don’t really know why but cross-functional projects and programmes have a reputation of being trouble makers and being a common source of risk. One major system integrator rates having more than one division of their own company involved in a project as being the highest risk factor’

‘This makes sense to me’, says Bob, ‘in my last company we had endless problems caused by different divisions heading toward different objectives and timescales, and especially, assigning different priorities. Still this doesn’t apply to us, does it?’

Jason draws a large cross over the key box on the slide (Strategic Vision) to emphasis the point that SpendItNow do not have any form of vision of the future and nor do they have a strategy for getting there and therefore no overall strategic portfolio. Jason points out that without these components they are really starting a top-down process half way up.

After some discussion they decide to sketch out the programmes and projects that are actually going on at the moment. They discover that they have three functional programmes, one per functional grouping within the company plus a whole series of minor projects. Most projects fall into one of the three functions but the loyalty card project, which should have been complete by this stage, had two components: one in Stores Operations (which includes IT) and one in Purchasing and is therefore cross-divisional or cross-function initiative

They discuss the other projects and identify the key question of risk; how to define the level of uncertainty associated with each project. They also discuss the as-yet unformed e-Trolley project.

The directors seem impressed with Jason, his performance seems to go down well and Bob admires the way he handles the small audience. Jason actually finds this quite easy as it is something he has done many times before.

Part 4 - Bob worries about Jason

Thanks to Geoff Reiss for contributing this book