Where are we?

You now have a good idea of the work involved in the project and you can begin to see where different people might contribute. You must now make your schedule more robust, by introducing a healthy slice of reality into the project.

Just because you produce a document and write ‘Project schedule’ across the top doesn’t mean that it will happen. Many factors both within and outside your control will conspire to mess up your carefully crafted schedule.

Risks are things that may or may not happen. You can improve the chances of the project happening the way you want by applying the principles of risk management.

‘With any luck it will be OK’, and ‘how was I to know that that would happen’ are not professional project management attitudes.

Of course it is unreasonable to expect a project manager to be clairvoyant, but there are many so-called unforeseen events that could and should have been foreseen. Managing risk is not just about having contingency plans to help you survive problems.

Think about driving a car. Just because you are wearing a seat belt doesn’t mean that you can drive like a lunatic. It is always better to avoid an accident than to survive one. We all try to drive in such a way as to avoid accidents, but as we cannot control all the other lunatics on the road we wear our seat belt.

We should approach our projects in the same two-pronged manner; what can we do to reduce the chances of something going wrong, and how could we survive it if it does actually happen.

The approach to managing risks here is very simple, but very powerful. It consists of several steps, helping you focus on the most important risks, and guiding you towards ways of managing them.

Where does risk come from?

Risk comes from:

- Note: in simple projects you are usually focused on ‘negative risks’ or ‘threats’. The main Praxis framework also addresses ‘positive risks’ or ‘opportunities’

Anything that is new: new technology, new processes, new people (project team, customers, support personnel), new methods.

- Anything that is unclear: unclear objectives or constraints, unclear technical solution, unclear resource availability.

- Anything that takes place away from the project manager’s immediate sphere of influence and control.

Risk is magnified by distance away from the project manager (by the time the project manager gets to hear about a distant problem it may already be a full-blown crisis), so the sooner you identify and address a risk, the better.

How can you identify risk on your project?

This is one of the project management processes that really improve if you can involve other people. Try to get half an hour or so from people such as:

- Your colleagues.

- People likely to be involved in the project.

- Your boss, the sponsor, the customer (if you think they can contribute in an open-minded manner).

- At least one person who knows nothing about the details of your project.

Make sure that they are familiar with your project documentation (the definition, and any draft schedules you have produced so far).

A risk workshop in the form of a brainstorm can be an effective forum for identifying risks. Don’t edit what people say, and don’t criticise or ridicule their offerings. Note down all suggestions, but make that what they say is specific and detailed.

For example, on the Lake project, you may feel that ‘Bad weather’ is a risk. Well, it is, but this is just not detailed enough to manage. Specific bad weather risks to the Lake include:

- Continuous heavy rain during the pumping may delay the draining of the lake.

- High winds during the covering of the plants with plastic sheeting may make the whole exercise impossible.

- Sub-zero temperatures during the pumping may cause the pumps to fail.

- And so on….

Each of these risks needs to be managed in its own way, so must be specified separately.

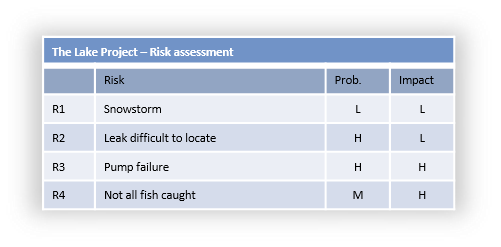

Assessing the risks

Once you have a complete list of risks you need to focus on the ones worth worrying about, and you can do this using a system of risk assessment.

It is based on the fact that every risk has only two characteristics that define its importance, namely the probability of occurring and the impact if it does occur.

Using a simple method of scoring of high, medium and low you can assess every risk, and then focus on the high probability / high impact risks.

Prevention is better than cure

The first thing you can do now is to focus on the probability of your chosen risks, and try to identify things you can do in the project that will reduce the probability from high down to something more acceptable (the equivalent of driving your car carefully). These actions are called risk responses.

Responses must be built into the schedule as they are actions that will be carried out. They may have time, cost and resource implications, so need to be justified to senior management, customers and sponsors.

Some examples for the Lake might include:

Risk: Pump breaks during use.

Prevention measures:

- Ask to see service records for the specific pumps.

- Make sure that the hire shop is qualified to deal with such pumps.

- Make sure that the water filters are clean and fully operational.

- Make sure that the pumps have oil and fuel of the correct grade.

You should now add these prevention measures into your schedule to make sure that you remember to do them at the right time. Unfortunately, you can do all of these things and the risk might still occur (it is unusual to find prevention measures that bring the risk to zero – you need another strategy to accomplish that).

Contingency plans

So, just as in the driving example, where you buckle up your seat belt ‘just in case’, you need some contingency plans, ‘just in case’.

You might hope that your contingency plans are a complete waste of effort, as you really want to complete the project without needing them but in some circumstances it might be worth actually testing a contingency plan in advance. If you have to fall back on it and it doesn’t work, then it is worse than useless as its presence may have lulled people into a false sense of security.

You wouldn’t usually clutter up your schedule with all the contingency activities (after all, you may never need them), but you may have to consider building in some research, practice and trigger activities.

Research activities are the activities you will carry out in advance, making sure the contingency plan is well founded. ‘Practice’ is what it says and triggers are activities in the main schedule that detect the need to activate a contingency plan at the right time.

Triggers are often things you would have done anyway. For example, a test of a piece of equipment before committing to its installation, or a progress meeting with a key supplier to verify delivery dates. These are triggers if you have identified contingency plans. If the equipment test fails or the meeting reveals delays they may trigger the implementation of your contingency plan.

So, in the Lake project, contingency plans and triggers might be:

Risk: Pump breaks during use:

Contingency:

- Have another pump on standby (may cost more money).

- Have a callout arrangement with an engineer.

- Buy lots of buckets and have the local Boy Scouts on standby.

Triggers:

- Pumps fails completely.

- Pump runs at below rated speed.

Detecting the fact that the pump is running slower than its rated speed may require an hourly check throughout the night. This is also a trigger.

Organising these contingency plans and triggers may take up more of your time, so you must put these activities into the schedule (just to make sure you remember to carry them out).

Other responses to risks

There are other ways to manage risk, of varying effectiveness, as follows:

-

Avoid: just don’t do the risky thing this way, or indeed, don’t do it at all.

-

Transfer: get someone else to do it, someone who may understand the technicalities better than you. Of course, this may reduce the technical risk, but it may also introduce higher control and communication risk.

-

Accept: some risks cannot be prevented (maybe you don’t have the know-how or the budget or the resources to undertake effective preventive measures) or their probability cannot be reduced at all, so they must simply be accepted.

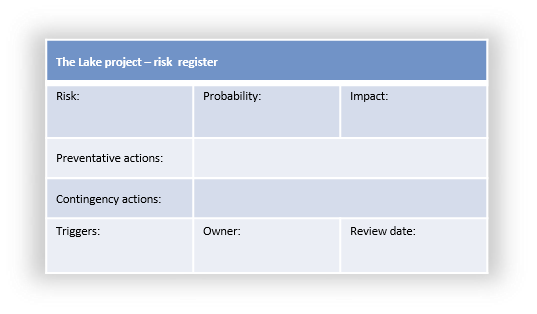

Documentation

It is most important that you write down the findings and suggestions coming out of your risk management, as you may have to justify extra project work to your boss, or the sponsor.

This risk register will be started at project initiation, and will be updated and reviewed all the way through the project. Finally it forms an essential input to the project closure and lessons learned activities.

Ongoing risk management

The risk register will be a living document, and must be revisited at key stages throughout the life of the project. Some risks will fade away and others will appear, and you must assess and manage them all. At the very least you should spend 10 minutes each week reviewing the risk register.

Summary

Risk management can convert a theoretical schedule into a practical schedule, one which has a much better chance of delivering the end result. The processes of risk management forces you to think critically about your project and to use some creativity in deciding how to manage the risks. The documentation you produce will be very useful both during and after the project.

Checklist

List all potential risks | Even the unlikely ones |

Assess their probability of occurring | Use a simple scoring system |

Assess their potential impact | Maybe on the entire project, maybe on time, cost, quality and benefits separately |

Focus on high probability – high impact risks | These are the ones you must manage |

Identify prevention measures | ...and build these into your plan |

Identify contingency measures | ...and maybe build in research or practice activities into the plan |

Identify triggers | …and build these into the plan |

Document your risk plans | The main document is the risk register |

Replan the project | These risk management activities will cost someone (probably you) some effort, so keep your documentation up-to-date |

Review and revise regularly throughout the project | You will not be able to see all the risks at the outset |

Further reading

These links to the Praxis web site explain how the concepts introduced in this chapter can be applied to projects that involve more people and more complex relationships.

An overview of risk management for more complex projects and programmes. | |

An encyclopaedia explanation of responses to both negative risks (threats) and positive risks (opportunities) |

Thanks to Mike Watson of Obsideo for providing this book