And so it happens. A mere 30 days pass before Bob, with Jason sitting at his right, opens an all-day workshop in the local conference centre. The agenda is simply the company’s project workload. Most of the board are present and quite a few senior managers. IT is especially well represented.

Bob does not say but does remember that before this meeting and in the first few hours and days after the event was arranged, blood was spilled. Fortunately businesses tend to use terms that over-dramatise the boardroom battles and wars between departments. The only real blood that was spilled leaked from a secretary's finger after a small accident with a pair of scissors.

But all sorts of silly, useless and misguided projects got summarily canned.

Calling the meeting had the effect of getting each Director to instigate a search for project expenditure within their specific divisions. This led to a minor witch-hunt amongst the senior managers and this in turn led to some hard words in the lower levels of management. A cascade of quiet cancellations and abandoning of projects immediately followed. Much of this was done on the basis that saying ’we cancelled that some time ago’ is a lot better that hearing the imperative: ‘cancel that’ even if ‘some time ago’ was actually yesterday morning.

A large number of miscellaneous bits of on-going work, too small to be regarded as projects but nevertheless collectively draining away a very significant amount of resource time failed to come to light. A number of people, each working on self-initiated mini-projects were allocating their time to assorted budget categories where the budget owner was not very watchful.

One team leader had had her team working on a little home-brewed idea to provide some new automatic reporting on the sales database. Her plan had been to collect a large number of brownie points by showing everyone the finished article and being only slightly smug about it.

The time spent on this work had been allocated to another project where the project manager didn’t seem to know why his budget was loaded by the addition of a group of activities that he knew nothing about.

This project was arguably not a terribly good idea as another team in another area were officially working on exactly the same problem, the wheel was therefore being invented twice.

The unofficial project team, and others like them, simply stopped work on the project with a sigh. Those teams where timesheets were not being done at all or where timesheet reports were so vague as to be less use than no timesheet at all, simply redirected their efforts. A number of mini-projects got unceremoniously and quietly dumped with phrases like ‘this one is going on hold for the moment’ and ‘we’ll have to switch priorities’ being employed. Thoughts and expressions mostly unprintable in a project management textbook were also widely employed.

By the time the away day workshop starts, only projects that at least make some kind of sense, or are so far down the track as to be unstoppable, have survived. The lack of smugness and the slightly worried brows of the team prove the value that workshop has already delivered and removes any danger of Bob and Jason looking like the Spanish Inquisition.

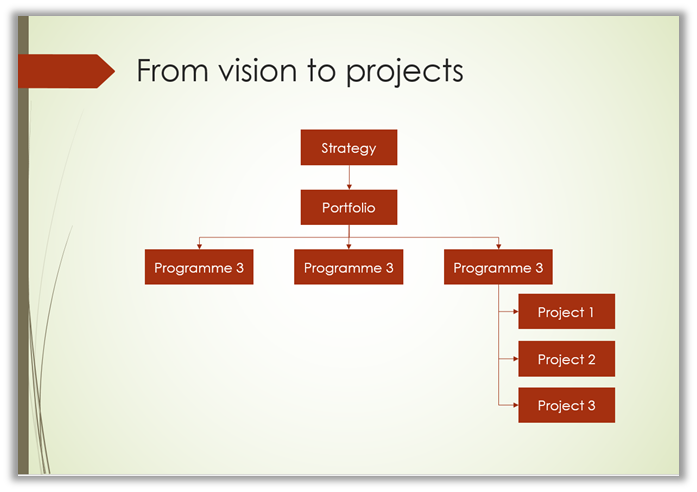

Jason starts off by presenting the overall structure diagram from the framework summarising the overall portfolio management process.

He leads the discussion and gets on with the business of the day explaining how the diagram shows that an organisation’s vision of the future should lead to portfolio management – the process of identifying and authorising programmes and projects of work. Portfolio management at a strategic level leads to the definition of programmes and these in turn lead to specific projects. He points out that there will be normally a range of independent projects as well.

The diagram also suggests the roles people should take, all of which leads to a smoothly run business with good control over its programmes and projects. This is a very high level overview of the framework and there is much greater detail which Jason says they will keep for later.

He tries to warm up his audience and to get them to think about the overall vision and strategy of the organisation.

Jason then proposes that they think of about the programmes and their benefits.

He says, ‘Once we have defined our programmes it will be a simple matter to define the projects that will best deliver the programme and its benefits. It is quite rare for a single project to deliver benefits, it nearly always take a few projects, managed together as a programme to maximize the return on investment.

‘The strategy outlines where our business should be going, our collective ambitions and aims. Benefits arise from the changes or improvements deliver to the organisation and the projects and programmes are a way of delivering those changes.’

He goes on to explain:

‘Projects create outputs.

‘Programmes combine outputs to create an outcome.

‘The organisation utilises the outcome and realises benefits. The benefits are measures of the improvement achieved. All of these must be consistent with the strategic vision’

‘For example’, he says, ‘we might want to enter the French market with the intention of stemming the huge drop we have observed in alcohol and tobacco sales in our stores near the South coast ports. To do that we would need to acquire some stores in the right locations, extend our computer systems into those stores and add the ability to work with and convert Euros, set up a new marketing and point-of-sale team to work in French and so on.

‘We could probably calculate the income levels we might expect over time without the change and the levels we might expect with the change. We can estimate the investments we will need to make and this means identifying the projects we need to undertake along with their likely costs. We can also estimate the demand each project will make on our own people.

‘By combining the investments, benefits and resource demands of the portfolio any organisation can take sensible decisions about all current and possible projects and programmes.’

Bob realises that Jason’s occasional ability to put a foot straight into the nearest available cowpat has surfaced again. Bright, young Jason has just told the mature and experienced board that they have been making non-sensible decisions for some years. Bob thinks he had better wade in, first slightly attacking and then supportively.

‘That is an approach but there are two points in my mind. In the example you just gave you said we would have to handle Euros. Now there might be many projects that share this need such that we are already getting ready for Euros when we think about the French market – how would we deal with that?’

Jason says ’that kind of thing is very common. Sometimes one project contributes to a wide range of different benefits and in different ways. Some people categorise their projects into three types:

Direct: projects that contribute to direct benefits.

Enabling: projects that deliver no direct benefit but which are vital to the delivery of a whole range of benefits from other projects – your Euro project?

Passenger: projects that can only add to benefits expected from other projects.

‘Also’, Jason continues, ‘it is not hard to draw a diagram connecting benefits to programmes and projects. I hope you are familiar with a benefits map……?’

Jason’s eyes sweep the room searching for anyone prepared to announce their lack of knowledge on this topic. His eyes cloud over slightly when he realises where he learned and used this technique. When he worked as a consultant he would frequently challenge everyone to admit that they don’t know about some technique before proceeding to blind them with his expert knowledge of it. But at SpendItNow he is part of the same team and he needs them to understand.

He quickly moves on.A combination of all Jason's presentations is available here in Anna's files

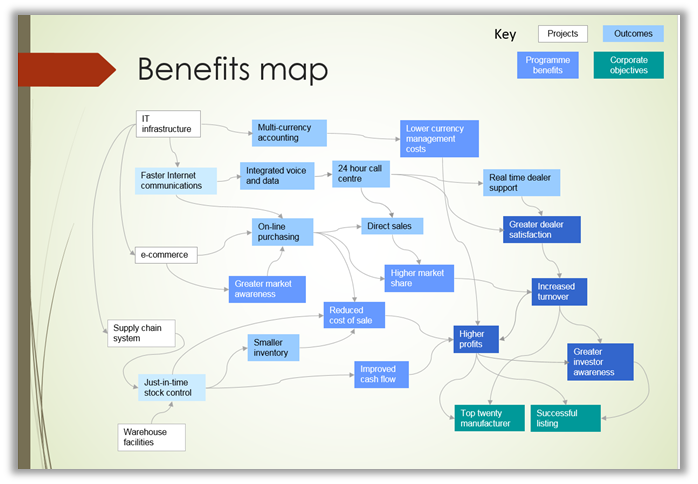

‘Well a benefits map shows the benefits we aim to deliver and implications they have for change at different levels and locations of the organisation. Here’s one I prepared when I was doing a consultancy job for Brook Bicycles, just down the road from here. They’ve given me permission to use it as an example.’

Jason brings up a slide to show the example benefits map and asks everyone to note that most benefits are achieved through a number of outcomes and that each outcome is supported in turn by a number of outputs.

He goes on to explain ‘A single output may contribute to multiple outcomes and a single outcome may depend on multiple outputs. The relationships between outcomes and benefits may be equally diverse’.

They furiously agree that the impact of change is a major barrier to the achievement of most benefit and any improvements in understanding at the ‘shop floor level’ can only be a big help. Most people have absolutely no idea why they are being asked to change something and most people dislike change of any kind so the whole thing makes them suspicious and often cynical of their management’s motivation.

Once this concept and the language it uses has been absorbed, and trying to resist a slight smirk, Jason asks Bob, ’You said you had two points?

Bob racks his brain for his second point and finds it third drawer down on the left. He wanted to address the slight insult to the directors that Jason had made earlier – the one about them not making sensible decisions.

‘You are making this sound like quite a mechanical process but it is true to say that this company, like many others, has been doing loads of projects and been very successful to date relying on something other than this technique?’

Jason gets Bob’s point in a flash and realises that some compliments are called for: ‘Please don’t get the idea this is a mechanical process. It is only a framework within which experienced and knowledgeable people can make decisions. That knowledge, experience and those ‘hunches’ if you like, are all what makes a board and therefore a company work really well.’

The non-executive director has risen from his somnambulant state and asks a question that hints at what he has missed. Fortunately for him it is not that unreasonable a question.

‘Is a benefit part of a project or is a project part of a benefit?’

Jason replies that benefits and projects are separate. A few projects have only one benefit or, to look at it a different way, some benefits are achieved through only one project. But in most cases there is a many-to-many relationship between projects, outputs, outcomes and benefits, which is why we group these projects into programmes.

Jason explains that starting off with a single project and trying to understand if it is viable is worthy but does not address a number of key issues connected with the other projects running at the same time and those planned for the near future.

He writes some key words on a handy flipchart and explains each one

Prioritisation : Where is this project or programme in terms of priority relative to others?

Resources : What resources does it require and how does that fit with the availability of resources in the organisation?

Logical dependencies: Some projects logically depend on other projects. For example a multi-site software implementation project may depend on the installation of a new cloud based infrastructure. What projects depend on the project under consideration and on what projects does it, in turn, depend?

Shared benefits: Some benefits depend on a group of projects. For example a new hospital ward is only useful when the building project, equipment commissioning and the project to provide the staff and support are all complete. A delay in any one of those three separate projects will prevent the opening of the ward.

Degree of change : Most organisations recognise that there is a non-numeric but still relevant, maximum and sensible level of change that an organisation can deal with. This applies to the organisation as a whole but also to separate departments, groups, functions and individuals.

Only by examining the overall portfolio can this be understood and considered.

‘But,’ says Jason ‘there is much of this technique we cannot use today as we don’t have ways of collecting all the necessary information. So we are going to rely on your expertise to estimate and comment on each project, programme and benefit.

‘So let’s take a look at our whole portfolio. In principle, it will look something like this’. He calls up another slide.

‘This should ideally be a top down process’, he explains ‘but as we have a number of projects already up and running we need to think these through in terms of our strategy.

‘Starting from the bottom up, you can see that projects are grouped into programmes and these programmes are grouped under the overall portfolio and this relates to the organisation’s vision.

‘Also whilst many organisations break their projects into functional areas there are often cross-functional projects and these often cause the most problems.’

The ever-interested CFO pops a question: ‘Are you saying we should merge our programmes into one overall portfolio?’

‘No, not just yet. Firstly we should get a better understanding of our important projects and programmes.’

Everyone’s thoughts turned to Bob’s recent article in the house magazine.

Jason pauses for breath and sips his ever-present water: ‘Do we have a strategy for the future and can we express it in a few words?’ Jason avoids the vision element at this stage as this would probably take all day to explain, never mind resolve.

A long and rambling conversation follows which, unsurprisingly does not end with a degree of agreement on the challenges the organisation faces.

Based on what he knows the company is already doing, Jason proposes a brief strategic statement:

In order to retain market share, SpendItNow must increase customer volume by 8%. This will be achieved by increasing retail space and widening the product range.

The Retail Director is keen to get on and says: ‘Let’s move on to the projects.’

Jason is less keen to do so: ‘Let’s see what initiatives we might set up to deliver this strategy. For example if we want to get deeper into the larger store marketplace do we need to build some new large stores, buy some or extend stores we already have?’

‘All of the above’, says the Retail Director who finds himself getting enthusiastic about all this despite his earlier cynicism.

Having swung back to talk about overall, long term strategy they do agree that they all wish the business to grow - and growth for SpendItNow translates into larger stores. For some this was so basic as to be under the level of consciousness.

For the director who nodded off early in the day the whole discussion is definitely below his level of consciousness as he has again slipped into slumber. It appears that his wife has recently given birth and the baby is causing them both sleep deprivation.

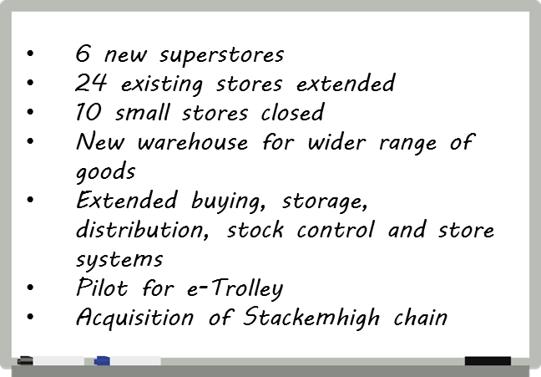

After a discussion in which the Retail Director plays a large role, some general points are agreed about the opening of large stores, the closing of some smaller ones and assorted extensions to existing stores. This is all expressed in very general terms and only occasionally are specific stores mentioned and only then as examples.

The Retail Director knows the number of stores and can quickly relate them to size expressed in terms of floor area, turnover and number of tills: ‘So in summary,’ he says, ‘today we have two superstores, 50 medium sized units most of which are in outer-suburban areas and 35 small stores in areas of high-population but with limited space.

‘If the trend for us should be towards more Superstores and larger stores, these smaller units are going to be very hard to expand and improve. I think we need to sell some of them off.’

Another director throws his proverbial hat into the proverbial ring: ‘The easiest way of quickly establishing ourselves with a much larger number of new, large stores is through acquisition.

‘As you all know I have been looking at StackemHigh and they have a number of suitable units very few of which compete geographically with any of our own stores. We both have stores near Gwent but apart from that they are already in areas we have identified as being our own target zones. Their typical unit is a new-build, out of town, large superstore and could very easily be changed to our brand. So by following through with the acquisition talks we could get on a fast track to quick expansion.’

They also decide to take Bob’s desire for a better check-out system as a specific example of an innovation that supports the strategy, partly because of his seniority, partly because an unstructured survey of customers showed this to be an issue and partly because it was suspected that their competitors were working on the same problem.

They decide that they simply do not know enough about Bob’s check-out ideas to seriously evaluate the idea. Jason translates this into a short introductory discussion about risk and how the risks associated with the project are high because the idea and the technologies are unknown at this early stage. They decide it is a strategic imperative to find out more about this idea which is becoming firmly established in their minds as the e-Trolley project.

They then realise that they have assembled the beginning of a strategic portfolio.

The IT Director feels it is time to contribute before his life becomes intolerable: ‘What you say is true but the barrier to this is going to be in the IT area. StackemHigh have a completely different approach to IT systems and we could not easily integrate their systems with ours.’

He would, at this point, normally dive off into long technical discussions about the differences between distributed and centralised databases and multi-access processing but somehow such topics seem too detailed for this level of conversation. With an extreme personal effort of will he stays at the high level:

‘We would need to install whole new systems in their stores as part of the refit and arrange some kind of data transfer from their legacy systems to our own databases. If we don’t do that we will not be able to take full advantage of our buying power, we will be prevented from using our loyalty cards in these shops and I have no idea how we would work stock control and pricing.

'So yes, by all means, let’s go ahead with the take-over but please do not forget that the IT side will take nearly a quarter of my team for the best part of a year, and that’s before we even consider the e-Trolley.

'We can do everything eventually but we can’t do everything today. Miracles, in IT, take time.’

This news does not go down well just as bad news has a habit of not doing. The one-liner about miracles taking time helped to give the bad news something soft to land on when it eventually stopped going down.

In a fairly rough and ready way they start taking the process to its next stage by trying to estimate what work they could actually handle in the next year. Jason makes notes on a flip chart.

Bob notes with satisfaction that his brainwave has earned itself a name – the e-Trolley project – a shopping trolley that will automate the customer’s check out process.

‘There are two issues to face,’ Jason explains, ‘There is the hard, quantitative ability of the resources to deliver new work in IT, retail, PR and so on and it should be possible to estimate at a broad level the resources that will be required for each initiative and to compare this with the availability we either have or can get. I know it is usually possible to increase resources, given enough notice. This can be done by hiring in contractors or expanding the work force and some allowances can be made for this.

‘And we cannot forget the business as usual workload – known these days as BAU – and the non-project workload.

‘Most people,’ he explains, ’have a normal job to do apart from their project workload and this can be thought of as a very high priority project. BAU has to be considered if we are to plan realistically with the resources we can actually make available for project work.

‘Additionally’, Jason smiles at the group,’ people like to take holidays, get sick, go off on training courses and take maternity and paternity leave. We should assemble data on these as well to ensure reasonable allowances are made.

‘But there is also the change limit – the impact of change on the organisation and specific groups within it.

Organisations that make a lot of simultaneous changes tend to get overloaded with change and this is much harder to estimate and prepare for. Some organisations that have adopted too many initiatives have floundered as some of those changes have been delivered but others have not and staff were de-motivated.’

Jason does not elaborate on his previous employer and ‘big four’ consultancy that had made exactly this mistake. That this catastrophe had taken place within their own organisation and not for a client made it worse.

The result had included a great deal of introspection by people who thought that ‘we of all people know how to run projects’; the creation of a new system for approving internal projects; the premature ending of a number of aspiring project managers’ careers; the incidental and unofficial creation and transfer of some people to the new ‘scapegoat’ resource pool and a few departures of disaffected staff.

However, he does talk a little about a contour of change.This he explains, refers to the fact that change can effect an organisation in a patchy way. There is a contour, which if it were possible to sketch, would show that some groups are hardly affected by change at all and yet others suffer from a wide range of simultaneous changes which they find confusing, overwhelming and very hard to deal with. Such people are unlikely to have great respect for their management.

So Jason pleads for a small number of carefully selected programmes and projects that are:

- Strategically aligned

- Highly beneficial

- Within the capacity of the organisation’s ability to change

- Within the capacity of the organisation to accept change

One athletic looking director speaks aloud a thought that is currently coursing through a number of brains: ‘Surely you are saying that the way to improve on the delivery of projects and programmes is simply to take on fewer of them? That seems a bit like reducing your time for a marathon by shortening the length of the race’

Jason has heard this before: ‘It is better to run and complete 4 half marathons than to fail to finish in 2 full races. We will be better off if we set and achieve some objectives than if we set and don’t achieve all of our possible targets. What is important is the number and value of the benefits we deliver rather than the number of projects we start’

The conversation moves on to setting targets for benefit delivery. It takes some time for some of the board to get their heads round the difference between an output and a benefit. They decide that a new store is an output, the increase in income from that store is a benefit. A new warehouse or goods handling mechanism would be an output but reduced handling costs and reduced damage would be benefits.

They decide that a new IT system is a deliverable but, with some humour, some mention that they have never seen any benefit from any IT system ever. The IT Director asks if better information is a benefit.

‘That raises a good question’, says Jason. ‘It is a benefit to the people receiving the information as they are in a more informed position. Such people are called stakeholders as they have a stake in the project or programme’.

‘Some stakeholders will benefit from a programme but many will not. A group of people who are to be made redundant by a cost cutting exercise or replaced by some technology are clearly stakeholders who will not benefit from the change.

‘Project and programme managers talk about stakeholder management being a process of identifying all stakeholders and their interests. Some managers find the concept of disbenefit useful as it describes the negative effect some changes have on some people.

‘So we must decide if we are talking about benefits owned by the whole organisation or benefits to the many and varied stakeholders in the organisation. When we talk about benefit management I think we must concentrate on benefits to the whole organisation.

The Retail Director asks if all benefits are financial.

Jason explains that financial benefits are important to many organisations but there are other types of benefits and some organisations have a mixture of financial and non-financial benefits and some have only non-financial benefits.

‘Government’, he says’ spends considerable time considering non-financial benefits. Think for a moment about education, health and social security where you will see the objective is to balance delivery of a range of services and the cost of running the operation. I do not think we should get into the issue right now but many people are using the Balanced Scorecard approach to define their non-financial strategies so that the impact a programme will have can be approximated and aligned with an expressed strategy.’

A number of people are prepared to admit not knowing much about Balanced Scorecards so Jason briefly explains.

‘A Balanced Scorecard provides four perspectives each relating to major non-financial measure of the organisation’s perceived success such as customer satisfaction, staff motivation, image in the market. The original authors did propose their own set of four perspectives but there is no reason why an organisation should not choose its own. Each perspective also contains a number of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Each KPI should preferably be measurable and include items such as:

- % of staff leaving the organisation per annum

- levels of customer satisfaction derived from customer surveys

- lengths of queues or waiting times

- amount of time taken to answer support calls

- % of repeat customers

- levels of complaints

- levels of wastage and theft

‘KPIs are therefore measures of the success of the organisation in non-financial terms. The amount of impact that a programme will or does have on the organisation in non-financial terms can be thought about and sometimes measured in terms of these KPIs.

‘KPIs may vary considerably between organisations reflecting the organisation’s functions, purposes and priorities.’

The CFO listens to this short discussion on KPIs but maintains the view that all benefits in the end come back to hard cash. ‘I’ve not worked for government, but there is no point of improving our customer loyalty levels unless they come back and spend money in our stores. There is no value in a better material handling mechanism unless it reduces the wage bill and the cost of damaged goods. In a business like ours, there is only hard cash at the end of the day.’

Whilst they all agree this is the case they do recognise that some non-financial benefits are very hard and perhaps impossible to translate into cash. ‘What part of our total turnover can be regarded as due to an increase in customer loyalty?’ asks Bob, ‘How does our advertising help our bottom line?’

In the end they all accept that it is impractical to think about anything other than both financial and non-financial benefits and that they need to prioritise their own non-financial benefits in some way based on the idea of Key Performance Indicators.

‘In these terms can we think about the benefits of some of the programmes and projects we have identified? Let’s start with the e-Trolley idea. What might it achieve?’

Part 4 - The e-Trolley, justified

Thanks to Geoff Reiss for contributing this book