Anna spends a commuting train journey thinking about things that can go wrong with the project. She discounts the risk of earthquake, tempest, hurricane and being struck by lightning as they are just too unlikely and if they did happen her project would be way down the list of problems facing the company. On the other hand she knows that very unlikely things do happen.

She remembered a girlfriend’s story about an accident-prone husband who had, when they were unsuccessfully ‘trying for a family’, set off for the sperm bank for a count. He had managed to drop his fresh sperm sample onto the marble floor in the lobby of their block of flats smashing its jar just as her parents arrived for lunch one day.

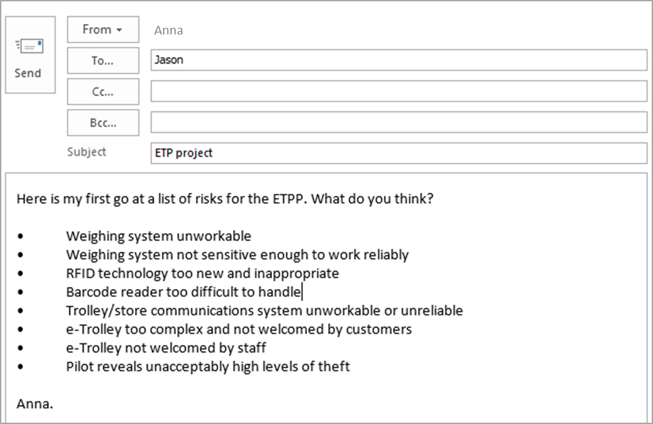

Dragging her mind back to supermarket trolleys she typed her first list and emailed it to Jason. It looks like this:

Jason rather unkindly takes the list to pieces and sends back this email the next day. He happened to be in a terrible mood and it shows.

This gives Anna pause for thought. That Jason was quite right did not excuse his unhelpful approach. A few choice and unladylike names for Jason meandered through Anna’s mind. She thought about a new register starting with: project manager walks out in a huff leading to collapse of project. She thinks perhaps Jason had had a bad time with his girlfriend or whatever.

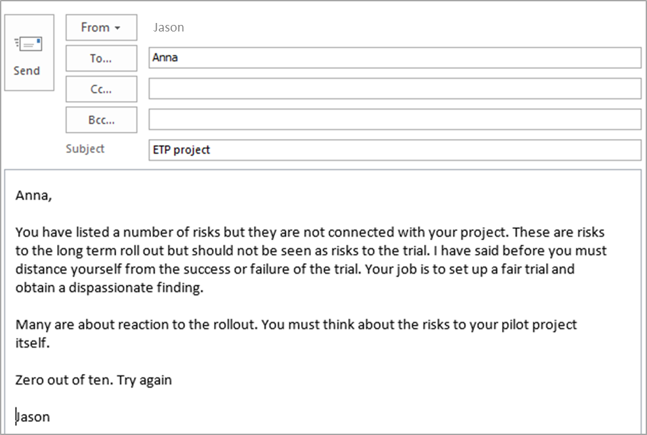

Once she has calmed down she tries again. Her second risk register is much nearer the mark.

ETP Project Risk register

|

She pops rounds to Jason’s office to run through this list.

Jason feels much happier with this list plus his mood has by now improved. He says that the list shows the importance of letting everyone know about these sorts of risk. Anna had brought together a list that will show many people in the organisation how their contribution to the project or at least a contribution from an area they have responsibility for, could make or break the project. The list, once published, will also made it clear that responsibility for the success of the project is shared around the organisation.

Anna has also started, especially in the last two items, to distance herself from the results of the trial by associating herself with a fair trial rather than the any particular outcome of the trial.

Jason asks if there were any steps they could initiate to reduce those risks, to mitigate them. He explains how in some projects the team take out insurance policies. Some building sites, especially renovations of famous structures, are protected by a temporary external envelope to allow work to proceed even in extremely bad weather.

They agree that by getting Bob to publicly back the project and getting buy-in from the senior management they should get support and commitment from the important groups within the company. One of the risks related to Bob himself.

Jason outlines a worry to Anna: ‘Throughout the project there will be times when you need a sponsor. We talked about this role before but left it unnamed and I have been thinking about it.’

‘Bob is keen on this project but he probably won’t really have enough time to make the day to day decisions you will need. This is a specific element of the “Lack of senior management support leading to low prioritisation of work” risk you listed, but Bob will just say that he will make time if you raise it with him. I think we need to emphasise the role of a sponsor who will take the client role and make those rapid decisions. It will reduce the likelihood of that risk significantly.

‘Now, can we summarise the steps we think need to be taken to mitigate the risks and give each risk an owner? You should identify an owner for each risk and give that individual the responsibility for monitoring and reporting the risk, and also suggesting if and when steps should be taken.’

‘Hold on’, says Anna, ‘I can’t give these senior managers jobs to do – I can’t tell them to take responsibility for these risks. If I tried I would risk whatever support I might get from them in one easy step.’

‘You’re right – but you can suggest that responsibility needs to be taken and add the risk that these the other risks do not have owners and for that matter that the organisation does not have experience at risk management.

‘I think you will have to take responsibility for some risks yourself. What can you do about the unusual nature of the project and the problems that gives you in setting a timescale and budget?’

After a moment’s thought Anna replies. ‘I can try to set expectations that the project may exceed its budget and timescale as this is an innovative project totally outside of our experience. Have you any better ideas?’

‘Classical project management suggests that you allow a management reserve for unknown factors. The London Olympic team announced a £2bn reserve at the start of the programme that led up to the 2012 games. This is an amount of money or time, or both, that is set aside to allow for just this sort of thing. Reserves can have owners and there can be more than one. In this case I suggest you have quite a large reserve owned by the sponsor who may release additional funds if you put forward a compelling case.

‘If you do spend it all you still bring the project in on budget. If you don’t need it you deliver the project under budget. It is very similar with a time reserve.’

In an innovative project like this I recommend a 10-15% reserve. In other words when you develop and plan and a budget add an item called management reserve and give it a value equal to 10-15% of everything else together. If your budget is £1,000,000 you would give yourself a £100,000 - £150,000 reserve. If your timescale is 10 months grab another month to six weeks as buffer.’

Anna sees some practical problems with this approach. ‘How can I tell Bob I want to have £100,000 just in case? It’s an awful lot of dosh.’

‘It might seem like a lot but it could make the difference between success and failure. I have two arguments to use.

Are you ready for a short lecture?’

They refresh their cups of sparkling water from the small fridge that has recently appeared in Jason’s office.

‘Go for it.’, says Anna.

Jason has made a few notes. ‘I have three topics.

Number 1: Runners, repeaters and strangers

Number 2: The reducing reserve theory

Number 3: Promise little, deliver much’

Anna settles back to absorb Jason’s impromptu one-to-one lecture.

‘Number 1: Runners, repeaters and strangers

‘Many organisations run a very wide variety of projects and understand that different approaches are needed to different projects. They talk about a range of project types – this is nothing to do with the content of the projects, it is to do with the level of familiarity they have with the type of work.

‘You can see that the appropriate methods, the type and size of team and degree of risk will vary across the range of projects.

‘Some organisations classify their projects into three groups relating to the level of familiarity they have with the type of work: runners, repeaters and strangers.

‘Runners are the run of the mill projects that the organisation undertakes very frequently. There is often a great deal of knowledge about such projects. In the case of SpendItNow we have opened a lot of stores and we know a great deal about the work that will be required, the people we will need and the problems we will face. I found that the retail group have a database of store fit-out costs and can give you a pretty good estimate of costs based simply on the floor area of the store and a few other details. There is a standard store fitting-out project schedule listing all the likely activities that can be used as a template for each new store project – you just need to adjust the timescale for the size of the project and decide on a few options about peripheral items like car parking. We can call a normal store opening project a runner.

‘Repeaters are the type of project that an organisation undertakes now and then. These are less frequent but still use the expertise within the organisation and there is usually some background data on previous projects but it will not be in a structured form. We do have a few store-within-stores where our store is a part of a larger hypermarket complex. There are only three such stores and they have different problems as we have to work much more closely with the hypermarket owners and their building team. For each project we have to develop a budget and a timescale depending on what we have to do and what the hypermarket owner expects to do. These store layouts vary a lot, there may be no shop front and we may be provided with heating and security and all sorts of other things. We might have regarded that kind of project as a repeater.

‘And finally we get strangers and I cannot think of a better example than the e-Trolley. We have zero experience of this kind of thing, we have little idea what to expect. There is no material from previous projects, no lessons learned. We are truly heading into the dark. These are called strangers and guess what - it’s normal to give them a special team who are better at managing unknown challenges and the wise organisation allows greater reserve due to the risk of the unknown. Does this make sense?’

Anna smiles that gently bitchy smile of hers. ‘Absolutely – the only thing I can’t understand is why everything IT does seems to be a stranger. But I see the point. If I can get the others to understand how unique this is I will get greater sympathy and support and no one will argue with the reserve I propose?’

Jason thinks that Anna may be getting carried away with this and feels he must balance the interests of the company.

‘Except me, that is. Now let’s move on to oil rigs’

Number 2: The reducing reserve theory

‘There is a lot of expertise in the world on the construction of oil-rigs. I am talking about those hugely expensive engineering marvels that get floated out into the North Sea, South China Sea or wherever and pump the oil from under the seabed.

‘These normally go through three stages: concept design, detail design and construction. At each of these three stages there is a Gate where the project team presents their current project to a group of very senior people in the oil company. Bear in mind that we are talking here about hundreds of millions of dollars being gambled on one engineering item. The project team puts forward their proposals to the board and seek approval to move to the next stage. The concept design is fairly cheap, detailed design is much more expensive and the construction phase has a huge cost and a huge risk.

However, as the project moves through these stages, the team learn more about the project and become more accurate with their thinking. In a sense becoming more accurate, itself, costs money and takes time.’

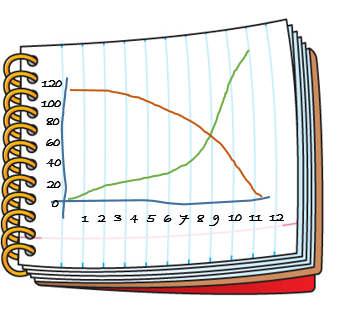

Jason sketches a simple chart on his note pad:

He explains: ‘The red line represents the amount of influence a project team has over the final cost of the oil-rig project. This starts off very high as they can execute the project in a wide range of different ways. But as the design progresses their options narrow. Once a contract is placed for the building work their ability to influence the final cost drop significantly - all they can do is choose cheaper door handles – and once the project is complete there is no possibility of changing anything at all.

‘The green line is the amount of money committed, not necessarily spent but committed in contracts. So as the project goes through the design stages the actual amount of money committed slowly rises until construction work begins when the cost rises sharply. Now why were we discussing this?’

‘I was starting to wonder about that – wasn’t it do with reserves?’ she asks.

‘Oh yes, well the oil companies accept that the greater the level of knowledge, the smaller degree of reserve. When a project is complete no reserve is required at all, but when it is just getting going there are a lot of unknown areas, hence the ability to influence the costs.

‘So they have a graph showing the level of accuracy the board should expect in cost and time estimates at each major phase of the design and build project life-cycle. This maps very closely to the level of reserve you will need on the ETP project’.

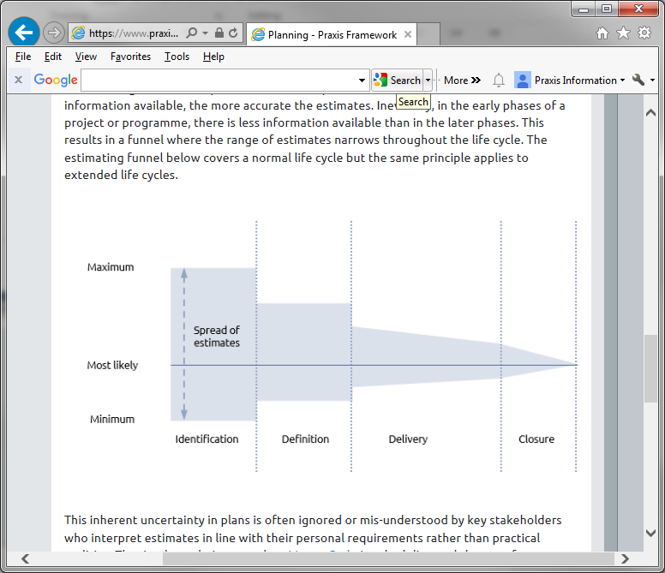

Jason calls up the framework’s planning page on his tablet.

‘You see that at the beginning of the project they expect budgets to be within a range of , say, +35% to –20% of budget. This should drop to plus 25% or minus 20% by the end the identification phase and finally somewhere around plus or minus 10% of the final figure before delivery begins. Of course the accuracy is only down to zero once the work is done.

‘If you can get this message across you can suggest a larger reserve now with the promise of reducing it when the exact nature of the project gets clearer. Get the idea?’

Anna nods vigorously. ‘Sure, but in the case of the overall e-Trolley roll out programme we are dealing with the equivalent of the identification phase aren’t we?’

‘That’s true, at the end of the pilot project you will only have a high level outline cost for the programme as a whole… but you do have much greater influence over the project. For example the total cost of the pilot is going to closely relate to the number of stores that take part in the pilot and we have yet to fix that. Let’s move on to my final point.

‘Number 3: Promise little, deliver much

‘There is a very strong tendency amongst project managers to create tight plans and budgets for mysterious reasons, sometimes on the basis that they will help the project get the go-ahead. What happens is a sort of bargaining process between the project manager and the sponsor where they strike a deal over the timescale and budget as if one is buying a carpet in a Middle Eastern souk.

‘Some senior managers take a pride in cutting 10% of the budget just for the fun of it. Perhaps they believe that all project managers add 10% for bargaining purposes.

See the article ‘The human side of risk management’ for a very real example of this.

‘On the other hand some project managers do add in huge reserves and hide them all over the place in budgets and timescales so that they can later be seen to bring either bring the project in on time or even better it. To the senior manager it is almost as bad to come in way under budget as way over budget as the spare cash could have been used to deliver more on the same or another project.

‘Project managers can only do this kind of thing on the kind of project I classed as a stranger as the budget for other kinds of work is too well known.

‘What I am saying here is that bearing in mind the unknown nature of the project it makes sense to be cautious at this stage. I will support caution as long as you are truthful with me and a long as we set up a cost monitoring and control process that avoids a surprise budget under-run or overrun at the end of the project. Let’s be cautious now and keep a close eye on costs, keep our budgets under control and end up very nearly smack on target. Is it a deal?’

‘It’s a deal’, nods Anna, thank you for all that. It has been an education. Its nearly lunchtime so I have better buy the teacher an apple – let’s head for the canteen.’

After lunch this sets Anna thinking more about risk and she adds a few items whilst expanding the list into a table. Whilst not really needing to, she gets her own back in a satisfactory way by ‘proposing’ Jason to own a number of risks. Revenge, she remembered, is a dish best served cold.

Anna tracks down Jason to ask a question and she knows to start with a compliment, ’Jason, you’ve been fantastically helpful with these standard documents and I understand that we have used the framework for many of these but shouldn’t SpendItNow have its own version of the framework and its own version of Jason on some more permanent basis?’

‘You are amazing’, says Jason, ‘you’ve just defined the perfect role for a Project Management Office or PMO. Let me explain. Many organisations have a PMO that is the source of good practice and standards for P3 management across the whole organisation. You can actually assume the ‘P’ in PMO stands for project and programme and portfolio.

‘Now PMOs can have different roles and they vary a lot.’

Anna settles back as Jason switches, once again, into lecture mode.

He continues, ‘The lowest form of PMO is more often referred to as a PSO or project support office. This is simply a travel agency and secretarial bureau. They organise flights and rail tickets and hotels for the project team as they move about the world and take care of documentation. Come to think of it there is one level lower: the PSO that exists simply to take minutes. But we’ll ignore them and start somewhere sensible.

‘A very popular form of PMO owns the company standards and guidelines and provides advice to the project teams on how to apply the standards. This type of PMO creates and maintains copies of the templates and documents outlining the project management processes. They keep these up to date and often make them available on an Intranet site.

‘They also have staff who know the processes and standards really well so then can help new project managers, or those with a bad memory, to follow the correct procedures. There are great advantages of having a consistent approach – it makes reporting so much easier and if a project manager leaves or gets run over by a bus it is simple to take over their work.

‘Some organisations take this a step further and made the PMO into a standards and guidelines police force. The PMO monitor projects and ensure that everyone complies with the published procedures. If they find, sorry when they find, a project that is not following procedure they report it to their line management. Line management then become the judge and jury and decide what to do with the miscreant. Occasionally the PMO become police, judge and jury and have the power to intervene in a project that is not being managed to their quality standards. This approach is never successful because it alienates the project and programme teams that the PMO should be helping.

‘Some PMOs have groups of specialists in areas such as planning, risk management or communication, and these are loaned out to project teams to help with good project management. Some even have technical people, experts in the technology of the company, who are available to help in technical areas. I remember an Architectural practice that specialised in sport centres and they had a pool of swimming pool experts that could be called on.

‘The best kind of PMO is the one that runs the organisation’s entire portfolio. They decide what projects and programmes to run and delegate and appoint managers to run them. In effect there is no difference between this type of PMO and a portfolio management team.

‘Now which of those least to most powerful PMOs sounds right for us?’

Anna thinks for a few moments: ‘I like the one that owns the methods and processes but only advises and reports. I can’t see us ever being a police state. I guess that such a group would be managed by you. How many people do you think you might have?’

‘Just one or two, I think, and it is really an extension of what I am doing for you already.

Meanwhile, back at the e-Trolley project, Anna visits the framework for information about investment appraisal and risk management and this helps her assemble a solid business case.

She realises that there is a very significant likelihood that she will find herself running the full roll-out programme if the pilot is a success. She is uncertain whether running that will be a good thing or bad thing. She is quite interested in the idea of the e-Trolley but by this stage sees it as an opportunity she can live without. Some other project viability studies are carried out by the individual who has the originally had the idea and these people tend to be much more optimistic about the benefits their work will deliver.

The framework confirms the value of having an independent group examine projects and programmes at the viability stage.

She visits a number of people and asks loads of questions many of which are very hard to answer. She talks to Mike Rovone, the company’s expert in weighing systems, about the practicalities of weighing devices, she talks to Sue Denim from Retail about the changes to the retail stores and she spends quite some time with Max Payne from IT talking about changes to the IT systems. It soon becomes clear that a new department will be required to weigh and record data about packaged products and Sue helps with defining this as well. There might be arguments over who should manage this new group.

Anna finishes her definition documentation and presents it to Bob and the board within the allotted month. She emphasizes to the CEO that this is only first attempt and she will be able to polish it into a true good practice example during the life of the project.

Nevertheless this is by far the best definition documentation ever produced within the company and Bob has no hesitation in using it as a model for all future projects. Anna modestly receives the congratulations for her excellent work and mentions Jason’s inputs. Most of the other directors are impressed even if begrudgingly in some cases.

The board are not asked to give the go ahead to the project just yet but they miss the point and discuss it anyway. Bob lets them rattle on and then points out how they cannot make a decision about the project until the definition documentation is complete.

As a compromise, the project gets a provisional go-ahead and Mike Rovone is appointed to two roles: project sponsor and, because of his specialist expertise in weighing, engineering consultant.

Anna is not sure that this is such a good idea. Having the same person fulfil the role of sponsor and team member on the same project could be a problem. Unfortunately, Mike was the only person that the board thought had time to do this.

Later on Jason explains that this is not unusual. Project sponsors are often appointed, not because they have the necessary skills, but simply because they have some spare time. He recommends that they just go with it for now but put recommendations in the SpendItNow version of the framework that this should not happen in the future. They agree that they cannot achieve a wholesale change of culture overnight; they have to take it one step at a time.

Anna makes a mental note to update the risk register.

That night she lays in bed with the slight feeling that she is on a slide – first the definition documentation, now running the pilot – she is in danger of becoming a project manager and that can only lead to becoming a programme manager and that can only lead to becoming director of programmes but first of all she had better make a success of the pilot.

Maybe first of all she should get some sleep.

Thanks to Geoff Reiss for contributing this book