Where are we?

Well, work has started on the project, and you need to know if the project is running to plan (time, cost and quality) and you may also have to take corrective action and report the status of the project.

The principles here are simple and are based upon the acronym FACE UP (i.e. we should ensure we face up to reality):

- F - Facts about progress

- A - Assurance about quality

- C - Confirmation of costs

- E - Early warning of potential problems

- U - Update the schedule

- P - Publish the schedule

When should we do this?

It is not necessary to be completely on top of every activity all the time. You may have agreed formal reporting times with the sponsor and if so, these will be your opportunities to measure genuine progress before you write your progress report.

If there is no agreement as to the frequency of progress reporting then you should find out quite quickly just what people are expecting. In any case you may prefer to set aside an hour every week to keep your paperwork up to date (schedule, risk register etc.) Then when you come to write a formal monthly report it will not take too long to find all the data.

Getting facts about progress

The usual way to find out what is going on in terms of project progress is to ask the people carrying out the activities.

The common method is to use that well-known approach, the ‘How’s it going?’ question.

This is just not good enough, as you will have little idea just what the answer means to you. Trying to measure the progress of an activity that is not yet complete is fraught with pitfalls. The person assigned to the activity might not understand the true nature of the question and give you an answer based more on their consumption of elapsed time rather than their progress through the activity. If someone says “it’s 50% complete” this could actually mean “50% of the allotted time has elapsed – but I’ve only done 20% of the work”.

The only way to be sure of exactly what has happened is through milestones. Everything else relies on guesswork, usually by other people.

Let us remind ourselves what a milestone looks like: the full format of a formal milestone definition has the following parts:

- The milestone name, in noun/verb format.

- The quality standard.

- The testing method.

- The person authorised to accept it.

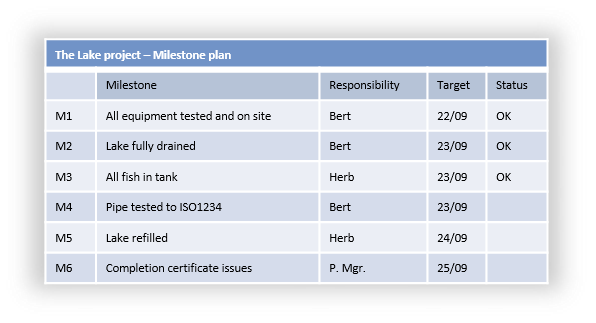

So, during the definition phase of the project you created a control framework, specifying milestones at key points throughout your project. It might be a good idea to make sure that each formal reporting point is accompanied by a milestone. This will give you the ability to measure exactly where you are, and so your progress report will be factual and reliable (you won’t be relying on the 50% complete nonsense).

The figure below shows the Lake case study milestone plan updated with a really simple notation:

Don’t forget that each milestone produces a deliverable that is signed off by an authorised person (ideally an independent person, i.e. not the project manager). You must collect and file each of these milestone documents as ongoing evidence of genuine progress.

So, for the Lake project, a major milestone identified was:

- Pipe repaired to ISO1234, tested and signed off by Bert Simpson (the foreman from Bodgitt & Duck, the Drainage Engineers).

If you have the certificate in your hand, signed off by Bert, you know exactly where you are on the project. If you don’t have the certificate, you know exactly where you are on the project. In the latter case you must now do some detailed investigation, going through with Bert all the activities leading up to the milestone, looking for the problem.

Assurance about quality

Well, this will come automatically if you rely on milestones for your control mechanism. Milestones specified in advance, with testing and acceptance criteria, will give you the assurance that not only are activities being completed but the output from each piece of work has been accepted.

Confirmation of costs

If you are running a project that requires budgetary control and reporting then now is the time to measure and report.

It is worth keeping any allowed tolerance in mind here, as your project may not be exactly on budget, but it might not matter if the over-run is within the agreed tolerance.

Once you have agreed with the sponsor what types of expenditure you must track (see the chapter on managing the budget), all you need to do is record the consumption of the budget as you spend it. Note ‘as you spend it’. Usually this is taken to mean ‘as you start each activity that involves a budgeted cost’, not when the money actually goes out of your organisation’s bank account.

In most cases you will have no idea when your project bills are actually paid, but the act of starting an activity commits the organisation to the expenditure, so this is a perfectly valid way of tracking expenditure.

Many organisations have computer systems in place that tell you (probably on a monthly basis) how much money has been spent on your project. These systems are notoriously inaccurate and the information can be weeks out of date, so many project managers keep their own simple records of expenditure based upon the assumption that work started is counted as money spent. It is often easier to track and analyse over- and under-spends due to factors such as poor estimating if you are doing it yourself.

Most sponsors will not want to see the detail of the budget, but will be happy with a summary. You, of course, must keep all the detail in order to control the project and produce the summary report.

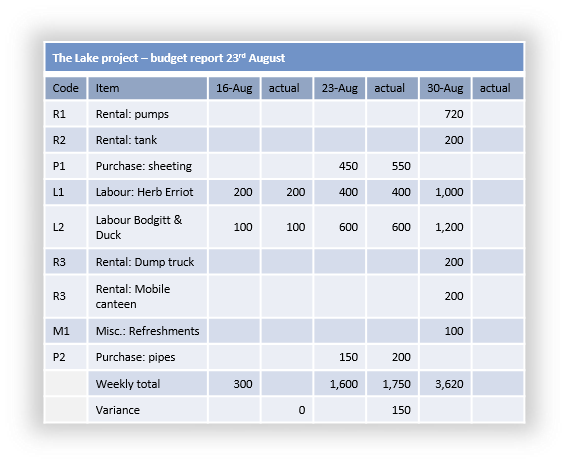

The figure above shows a budget report for the Lake project as at 23rd August. The sponsor can see that week commencing 23rd August over spent by €150. This report could also be summarised by the categories of expense, which may be easier for the sponsor to read.

It is worth spending a few moments at this point considering what your responsibilities might be if you are using outside suppliers, consultants etc. as part of your project team.

Once a contracted resource has either finished or reached an agreed intermediate invoicing point he/she will submit an invoice for the work done, or the goods supplied. The invoice will come to you, as you will be the only person who can say whether the project has received the correct value of goods or services. Your responsibility therefore is to check and approve the invoice for payment. It is most important that you keep a record of each invoice as you approve it, either by keeping a photocopy or making a diary entry somewhere (maybe in the project plan) to record what you have done.

You will then pass the invoice into your organisation’s accounts payable system for (eventual) payment.

The supplier will contact you if he/she feels that there is a delay in receiving the money for the work performed, as you were the one who commissioned it. Unfortunately you will have no idea if the money has actually moved from your organisation’s bank account to the bank of the supplier, but you must be able to prove quite quickly that you did indeed approve the invoice for payment, together with the date of approval.

Your next responsibility is to find who in the organisation handles accounts such as these and put the supplier in direct touch with the accounts payable person. Both parties will want you to get out of the way, as a project manager acting as an amateur accounts clerk will only mess things up for all concerned. So, keep a record of every invoice as you approve it.

Early warning of potential problems

Most sponsors like to feel that you are looking ahead, and one sure way to demonstrate this is to include in your progress report a brief analysis of risks and problems identified in the last period. This will only be a simple text report, listing the latest ‘nasties’ and, more importantly, your action plans for dealing with them.

The input to this part of the control process will come from two areas:

-

Things which you have identified as potential problems when previously ‘getting facts about progress’. These may be activity overruns in time or budget, quality failures, resource problems and so on.

-

Things about your project which other people have reported to you. These are often referred to as issues, although the terms really applies to your own issues as well.

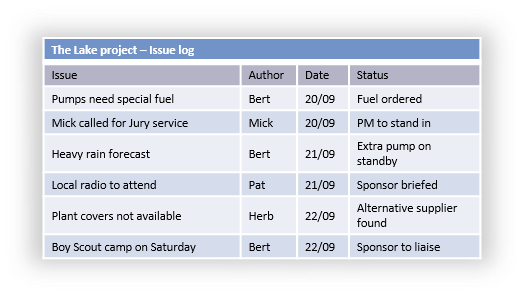

Managing issues

Note: On simple projects this broad definition of ‘issue’ works well. On larger projects with a more formal manager/sponsor relationship, Praxis defines issues in a more rigorous way.

You need to encourage people to report issues about your project. An issue is anything that anyone wants to report about the project.

At the very least an issue shows that there is somebody out there taking some interest in your project. Issues are good things, even if they may seem totally stupid and time wasting. By handling dumb issues well (positively and constructively) you may encourage that person to report the next issue they encounter, which could just be a real show-stopper as far as your project is concerned!

Issues can be:

-

Simple misunderstandings: someone hasn’t read your project brief, as is not aware of the scope of the project

-

Early warning of a risk: ‘have you heard…’ This type of issue can be very useful to you in keeping your risk management activity up to date.

-

A bug report: someone has found something wrong in one of your project deliverables and they are reporting that your product is not up to specification

-

A request for change: an issue may be the way in which someone reports that the specification itself needs to change; you may have to ‘convert’ this issue into a formal change request

-

A project management issue: the sponsor may be reporting that the budget has been cut by 50%, or a key resource has just gone sick.

You can see that each of these issue types needs to be dealt with in its own way, but a common feature of them all is that it can be very useful to record all issues in one issue log (just a simple list, with author, date and status). A simple analysis of the log may find, for example, that you are getting many issues from the same group of people, and this could indicate a training need, or a poor distribution list on a key document. This analysis will provide feedback on your success in communicating project information effectively.

Issues that turn into potential risks should be dealt with as new risks, as described in the chapter on managing risks.

Updating the schedule

Well, you should have learned a lot from your examination of milestones, tracking the budget, and dealing with issues. You should have learned two types of things:

-

Where are we today? Which activities have been completed satisfactorily and which are outstanding? How are the resources performing? How has the budget been consumed? Is the quality of the work up to standard? What have you learned about the project?

-

What does it means for the future? If there is a problem today can you think ahead and will this problem have an effect later in the project?

It is all very well knowing that you are two weeks late today but you must try to identify the potential future effect as well. Your assumptions list may help here. Perhaps you are late because one of your assumptions is proven invalid.

Does it have an effect later, because it is likely to be invalid there as well? You are allowed to be surprised by something unexpected, but not by the same thing three times.

If the project is ahead of schedule you need to think: are you creating problems elsewhere by forcing the pace on this project? It’s always nice to be ahead of the game, but it may be better overall to drop back to schedule.

The most common problem, of course, is that your project is running behind schedule in some way, either in time or in the fact that some work was completed incorrectly and has to be done again. If the delay falls outside the agreed level of tolerance then you must do something to correct it. It is probably better to discuss the situation with the sponsor and agree some corrective actions before you write your progress report, the report shouldn’t come as a nasty surprise!

Don’t forget to physically update your project plan. There are many ways of doing this:

-

Write ‘done’ (or something relevant) next to each activity on your activity list

-

Change the colour of activity that are completed (especially powerful if you are using a spreadsheet plan)

-

Draw a line through each completed activity; and if an activity is only 50% complete draw a line through 50% of the activity!

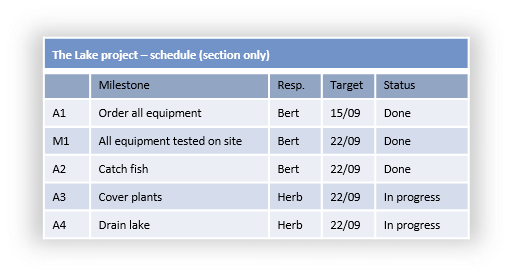

The next figure shows an example of the Lake project schedule with a very simple update of progress.

Corrective actions

If delays occur your choice of corrective actions is typically limited to:

-

Delay the target completion date, i.e. accept the delays.

-

Overlap some of the activities (sometimes called fast-tracking); this will involve taking some risks, but it may just shorten the project enough to keep you on the original schedule.

-

Increase the budget: spend more money to speed things up, usually by adding more resource (sometimes called crashing the schedule); this needs care as adding more people won’t necessarily speed things up?

-

Juggle with the resources: reassign people to focus on the slipping activities.

-

Reduce the scope: don’t do all the things you said you would do; create a phase 2 that will tidy up all the bits you need to leave out, or hand them over to someone else, or just don’t do them.

-

Reduce the quality; definitely last resort, but maybe you’ve drifted into a Rolls-Royce solution when a Mini would have done.

Try out various scenarios by creating several new versions of the schedule. Which course of action has the best effect with the least risk? Maybe this is the one you take to the sponsor.

What authority do you have?

Most project managers have very limited authority when it comes to action to correct a problem. You probably can’t decide to leave out half of the work just to get the project finished on time; nor can you draft in another squad of resources to speed things up. Your responsibility is to identify effective corrective actions and then convince someone else (the sponsor, usually) to accept your recommendations. If the sponsor says yes then you may have to re-baseline the schedule, as you will now be working on a new basis for the project.

The progress report

You now have all the information you need to write your progress report. Many organisations have a standard format for a progress report, but the content always comes down to the main items. Remember the acronym FACE, and make sure you have all the relevant information to hand. You can use FACE as the structure for a simple progress report, which may be all that your sponsor and/or boss requires.

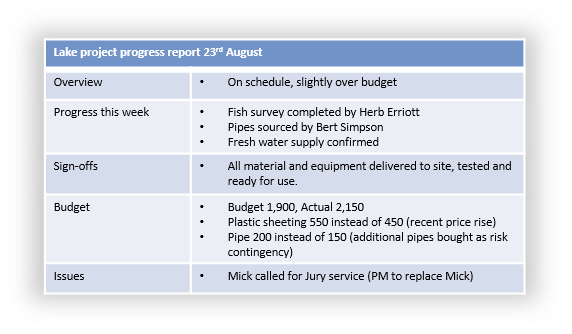

This figure shows a simple progress report for the Lake project, using FACE as the structure.

Publishing the schedule

Once you’ve updated the schedule and written a progress report. What are you going to do with them? At the very least you should issue a new version (yes, don’t forget to update the version number on all the changed documents) to:

- The sponsor and/or boss

- All resources directly involved in the project

- The project managers of all your external dependencies

And you should consider sending an updated plan to:

- Line managers of resources you are using

- Suppliers and subcontractors

- Any regulatory people (who will be inspecting and approving things in your project)

A smart project manager would, of course, keep a record of who has which version of which document, so that any updated documents can be sent to the relevant people with the minimum of fuss.

Summary

The acronym FACE UP really does sum up the responsibility of the project manager when it comes to measuring progress, replanning and reporting. The more accurate the measurement of progress (based on milestones) the better chance the project manager has of interpreting the information in a useful manner.

Keeping an open mind about the reporting of issues will make sure that the project manager hears what is going on in a timely manner.

Checklist

Collect accurate progress information | Based on milestones rather than activities |

Physically update the plan | Show progress, both good and bad |

Collect and file the sign-offs | These will provide a record of the delivery of quality products during the project |

Maintain a record of expenditure on the project | Assume that as each activity starts the expenditure is incurred |

Record all suppliers invoices passed for payment | And find out who handles these in your Accounts Payable department |

Document and analyse all incoming issues | Deal with risks using the risk management procedure; deal with requests for change using the change control procedure; deal with all issues sensitively |

Write a progress report | Keep it simple; more than one page will not be read by most bosses/sponsors |

Further reading

These links to the Praxis web site explain how the concepts introduced in this chapter can be applied to projects that involve more people and more complex relationships.

An overview of control for more complex projects and programmes. |

Thanks to Mike Watson of Obsideo for providing this book