General

Negotiation is a collective term for various mechanisms that seek to resolve differences between individuals, groups or companies. Its goals are to:

- find solutions to issues involving two or more parties;

- develop beneficial relationships between two or more parties.

The principles of negotiation are used in many different contexts. Two obvious applications are in conflict management and procurement. These two examples illustrate the breadth of situations where negotiation skills need to be applied. Addressing personal conflict often involves emotional and cultural issues whereas procurement negotiation is usually about contractual terms and conditions.

Whatever the context, there are common factors that exemplify a good negotiator:

- the ability to describe common goals and boundaries;

- emotional control and equal treatment of all parties;

- good listening and communication skills;

- thorough knowledge of bargaining tactics;

- an ability to close a negotiation in a way that secures the outcome.

A negotiation is often described as having one of two flavours competitive or collaborative.

Competitive negotiation is about getting the best deal for one party regardless of the needs and interests of the other. This can easily become a battle where the winner takes all and while competitive negotiation should be avoided, this may not always be possible.

Collaborative negotiation seeks to create scenario where all parties involved get part or all of what they were looking for from the negotiation. This approach tends to produce longer-term solutions and minimise the opportunity for future conflict.

Every individual has a natural preference for the way they negotiate and R.G. Shell’s model combines collaborating and competing with three other personal preferences based on Blake and Mouton’s managerial grid.

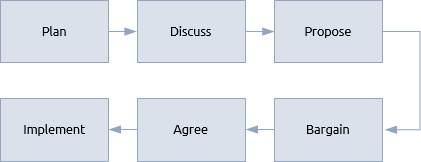

Regardless of whether the negotiation is competitive or collaborative, it usually follows a typical procedure:

-

Plan: All parties should prepare thoroughly. This includes gathering as much information as possible; setting goals for the outcome and agreeing an escalation route if the negotiation is unsuccessful. Each party should attempt to understand the cultural, commercial and ethical background of the others.

-

Discuss: Set the scene, identify the key issues and communicate the objectives. Listen, question and feedback regularly to confirm understanding.

-

Propose: Propose a solution that is clear and unambiguous.

-

Bargain: Discuss the proposal; communicate personal boundaries and areas of flexibility.

-

Agree: Reach agreement on the core issues; document what has been agreed and record any peripheral, outstanding items with timescales for resolving them.

-

Implement: Communicate the outcome of the negotiation as necessary, update any related P3 management documentation.

Negotiation is easy to get wrong. The cardinal sin is to enter into negotiations unprepared. This can easily lead to mistakes such as making opening offers that are clearly unacceptable to the other parties. Pressure to conclude negotiations and get on with the project or programme can result in rushed discussions that produce difficult to implement outcomes. It is important when bargaining to stay calm and know when to take a break. Whenever it takes place, the result of a negotiation will have repercussions throughout the remainder of the life cycle, so it is worth the investment to get it right (or as right as reasonably possible) before moving on.

Projects, programmes and portfolios

Project managers are often most involved in negotiation as they have direct involvement with the teams that deliver the project.

In the identification and definition phases of the life cycle requirements are being captured and initial plans produced. The project manager will need to balance the time, cost and scope requirements by negotiation with stakeholders with support from the sponsor.

During mobilisation and procurement, the project manager will need to negotiate internally with line managers in the matrix organisation and conduct more formal contract negotiations with potential suppliers. As the project progresses, conflicts between team members will arise and the project manager will need to negotiate solutions to conflicts.

In some cases there may be specialist help available from a support office. Even if there is not a dedicated support office, it’s important to know when to ask for help from specialists, for example the host organisation’s HR or legal departments.

In portfolios, programmes and more complex projects the range of negotiating scenarios gets broader and broader. P3 managers in these more complex situations need to understand negotiation in the context of delegation.

In particular, where a programme or portfolio is made up of multiple layers of management teams with delegated authority, a balance must be struck between removing autonomy from one level and gaining an advantage by collectively negotiating on behalf of the programme or portfolio as a whole.

The hierarchy of management teams also provides a mechanism for escalation should a negotiation at a lower level be unsuccessful. This should be explained in the relevant management plans, typically the resource management plan.