General

Procurement covers the acquisition from a supplier of the products and services required for completion of a project, programme or portfolio. Its goals are to:

- identify potential external suppliers;

- select external suppliers;

- obtain commitment to provision of internal resources.

An ‘external source’ represents any supplier from outside the host organisation. ‘Internal sources’ are departments or divisions within the host organisation.

Where the external source is a separate legal entity, the terms under which goods and services are procured will be the subject of a legal contract. When the source is part of the same organisation, a less formal approach such as a service-level agreement may be used.

Procurement typically incudes the acquisition of:

- ‘off the shelf’ goods and services;

- bespoke goods or services designed and provided specifically for the purchaser;

- advice or consultancy.

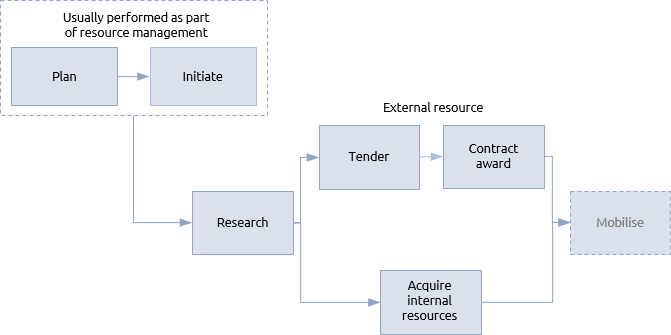

A procurement procedure will contain the following steps:

Research involves identifying the suppliers that have the required capability and may result in a long list of potential suppliers. In some cases the host organisation may have a regularly reviewed and up-to-date approved supplier list that reduces the work needed here.

A pre-qualification exercise aims to reduce the number of potential suppliers to a ‘short-list’. This can be achieved through various means such as sending out a pre-qualification questionnaire. This can clarify the capacity of the supplier, their willingness to tender, their financial stability and technical experience. It may also ask for references for similar work. Other projects or programmes may have experience of the same suppliers and their experience should be researched.

In a more mature organisation there should be references to suppliers in the knowledge management system and lessons learned in particular should be reviewed. In a less mature organisation a P3 manager may have to rely on seeking out and talking to other managers with relevant experiences.

Pre-qualification results in a short-list of suppliers who will be asked to provide a full bid against a defined statement of work, which could be a technical or functional specification. Final selection is often based on a formal tender. Tendering can be an extensive procedure in its own right, especially in some regulated industries, and a P3 manager may need to seek specialist help. It is important that the requirements are clear and all suppliers are given an equal chance of success.

Procurement records must be carefully maintained and archived to mitigate the risk of unsuccessful suppliers challenging the decision. Inputs to selection should include an appropriate risk analysis in addition to cost, time and quality considerations as defined in the resource management plan. Where possible, a reserve supplier should be identified. For critical goods and services the contract may be split amongst multiple suppliers as a form of risk mitigation.

The contract award step will involve the negotiation and agreement of a contract. Throughout the procurement procedure care must be taken to ensure that a contract is not casually entered into, and it should be made clear in all meetings and in associated documents that the proceedings are ‘subject to contract’.

All procurement involves risk and all aspects of the resource management plan must be prepared with risk management in mind. One example of this is the choice of payment methods for external suppliers.

Many resources will not be procured from external suppliers and will not be subject to a formal contract. Acquisition of internal resources is often not seen as a procurement exercise and does not result in a contract award. In some ways, this makes the acquisition of internal resources inherently more risky because the P3 manager is relying on verbal, non-binding commitments from departmental managers to provide the necessary resources when needed.

While tendering and legal contracts are not appropriate for internal resources, the P3 manager must take steps to formalise the relationship with internal suppliers. This may simply be written confirmation of the nature, quantity and timing of the resources being supplied or it may be a more formal service level agreement. Negotiating and agreeing these contracts should involve the sponsor, who can then provide seniority if there are issues of non-performance.

A package breakdown structure, based on a product or work breakdown structure, shows how work will be arranged in order to procure packages from different suppliers. The allocation of work to these packages is another important mechanism for managing risk.

For each package, the relative importance of time, cost and quality needs to be considered. For example, if a package is on the critical path there will be greater emphasis on time performance. Consciously addressing these factors greatly influences how contract incentives or service levels are designed.

Regardless of the detail of the procurement procedure, the management team must be to be able to demonstrate that it was conducted ethically.

Projects, programmes and portfolios

Smaller stand-alone projects will not be able justify a dedicated infrastructure for procurement. If the procurement needs are more complex than the project manager and sponsor can handle, they should use the services of the host organisation.

When a project needs the support of procurement specialists the manager must consider procurement implications as early in the life cycle as is practicable. Waiting until the full approval of the project at the end of the definition process may, for example, result in tender delays and long lead times adversely affecting the schedule. This early procurement is covered by the pre-authorisation work activity in both the definition process and the boundaries process.

Managers of smaller projects will have less opportunity to develop relationships with suppliers. In such situations procurement needs to ensure that the mechanisms for supplying the goods or services are as routine and low risk as possible.

At programme level the management team will need to decide which suppliers are to be managed at project level and which are to be managed at programme level. Typical situations to consider are:

- suppliers providing goods or services to multiple projects;

- specialist suppliers working on one project;

- risky contracts that need specialist procurement expertise;

- routine supplies;

- on-going maintenance that supports benefits realisation.

All these factors will be taken into account when preparing the resource management plan or, in work involving complex procurement, a specific procurement management plan.

Programmes, portfolios and large complex projects may enable economies of scale by consolidating and co-ordinating the procurement across otherwise autonomous packages of work. An overall resource management plan will govern how procurement is co-ordinated.

At these larger scales, the management team may be able to make use of partnering and alliancing to create long-term relationships with suppliers. It may also be able to set up framework contracts that agree unit prices for goods and services that can be called off by individual projects, sub-projects and so on. This greatly reduces the effort required for procurement at the lower levels.

Framework contracts are not appropriate for all good and services. There will still be many suppliers who have to be locally selected to meet the specific needs of individual projects and programmes. The top level procurement management plan should set out the basic procedure to be used and maintain a watching brief to identify common needs.