General

Contract management includes the negotiation, creation and administration of a contract between two or more parties. Its goals are to:

- support procurement by negotiating terms and conditions;

- document contractual agreements;

- monitor contractual performance;

- conclude contracts.

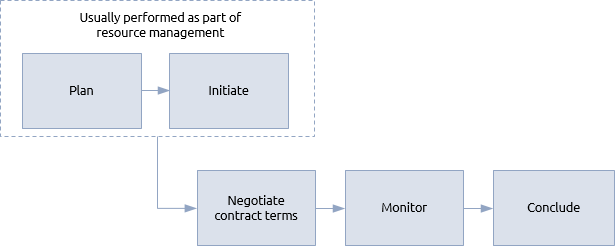

A typical procedure is shown below:

The procedure starts with the planning step that defines the scope and objectives of contract management and, if necessary, results in a contract management plan. The initiation step is performed once the work is approved and the resources needed to manage contracts are mobilised. Unless contract management is a major function within a project, programme or portfolio, it is likely that these steps will be part of a broader resource management procedure.

The first specific step is to negotiate contract terms with a supplier. A contract is an agreement made between two or more parties that creates legally binding obligations between them. The contract sets out those obligations and the actions that can be taken if they are not met.

Contracts are covered by contract law. Specialist advice should be sought to ensure that the legal ramifications of any proposed contract are fully understood.

While the law governing any contract will depend on the applicable jurisdiction, there are general principles that are universal. For example, there must be:

-

an offer made by one party, which is accepted by the other party or parties without qualification;

-

an intention to create a legal relationship between the parties and for the parties to be bound by the obligations in the contract;

-

a consideration passing from one party to the other in return for the provision of the goods or services covered by the contract;

-

clear and definite terms describing the conditions to which the parties are agreeing;

-

legality and lawfullness, with only properly incorporated firms or competent persons entering into the contracts.

A contract is required wherever goods or services are procured from external suppliers. This could simply constitute acceptance of standard terms and conditions or the creation of a specialist contract. The resource management plan should set the high-level conditions that contracts needs to implement. For example, if the plan stipulates that risk should be shared between parties, the contract needs incorporate the relevant payment methods and be drafted to make sure that risk is shared.

Many industries have standard forms of contract, such as the NEC3 range for construction and engineering. Some large organisations such as the UK's National Health Service have systems for constructing contracts from standard components. The main advantage of using standard forms of contract is that they take account of established best practice within the particular industry sector or organisation. The disadvantage is that it may not fully address all the areas required by the resource management plan for a particular project or programme.

Standard contracts don’t work for all situations. It is often the case that they have to be significantly tailored or a contract has to be built from scratch. These are called bespoke contracts and they are able to reflect the specific context and content of the work. The P3 manager will have to ensure that contracts are properly executed and should ensure they are subject to version control.

Whether standard or bespoke, all contracts have the same typical information and ‘conditions’, such as:

- general information about the parties to the contract;

- a description of the works or services;

- the legal system that the contract will use;

- the supplier’s responsibilities for design, approvals, assignment of such responsibilities and subcontracting;

- agreed milestones and completion date;

- change control, quality control, testing and defect rectification;

- payment methods and procedures;

- risk transfer and risk sharing, insurances;

- ownership of assets during the course of the contract, transfer of ownership including intellectual property (IP) and copyright;

- dispute management procedures and compensation (e.g. non-performance).

A statement of work (SoW) that defines the activities, deliverables, schedule and pricing can be a useful annex to the main contract (this is often referred to as a schedule and should not to be confused with a P3 time schedule). A SoW should be checked to ensure it doesn’t conflict with the main body of the contract and precedence needs to be clear.

If all parties perform as expected, it will not be necessary to resort to the contract to resolve a dispute, but of course relationships do falter and performance sometimes falls short of expectations. For the P3 manager, the contract can become a tool in conflict management, or more specifically, conflict resolution. The P3 manager should not immediately resort to the ‘letter of the law’ and must approach contractual conflict in the same measured way as any other form of conflict. There may be mitigating circumstances and the impact of destroying the relationship with a supplier must be weighed against the benefits of resolving the dispute in other ways.

The P3 manager must ensure that the management team are aware of how contractual obligations can be created inadvertently by poorly worded communications or inappropriate actions. Case law confirms that changes to a contract can be made without formal legal instructions being issued.

Once the contract is concluded, the P3 manager should confirm that the legal obligations created under the contract have been discharged. Items such as equipment warranties and defect liabilities may need to be administered for months, if not years, after the contract is concluded. The responsibilities for administrating such long-term liabilities need to be considered and where appropriate, documented in the follow-on actions report.

Projects, programmes and portfolios

The basic principles of contract law are the same regardless of how the work is managed, i.e. whether it is constituted as a project, programme or portfolio.

Smaller, non-complex projects or work that is performed entirely using internal resources may have no contracts at all. For more complex situations, internal relationships may be defined using service level agreements (SLAs) between an operational department and the project, programme or portfolio. These SLAs may adopt many of the principles of a contract.

As the complexity of the work increases, the P3 manager will need different levels of support in the creation and maintenance of contracts. In many situations procurement specialists will be competent to write and maintain contract documentation.

Where the work includes unusual or complex legal issues contract lawyers may be required.

As the scale and complexity of the work develops, co-ordination will be needed between multiple contracts. At programme or portfolio level the work will often be best served by framework contracts with suppliers that cover multiple projects rather than having separately negotiated contracts for project or work package.

In programmes, portfolios and large projects where there are multiple contracts, the P3 manager must understand the inter-dependencies between them. The actions of one supplier may adversely affect another leading to a contractual dispute. All inter-dependencies should be considered and the contracts drafted accordingly.