General

Investment appraisal is a collection of techniques used to identify the attractiveness of an investment. Its goals are:

- assess the viability of achieving the objectives;

- support the production of a business case.

Investment appraisal is very focused on the early phases of a project or programme and is performed in parallel with the early work on management plans and delivery plans.

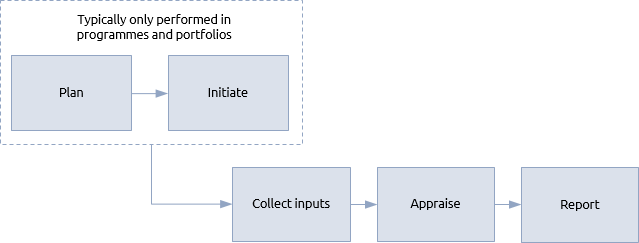

The existence of discrete planning and initiation steps for this function is entirely dependent upon the scale and complexity of the work. In programmes and portfolios these steps are necessary in order to establish consistent appraisal across all component projects and programmes. In projects it is much more likely that any planning and initiation of investment appraisal will be absorbed within the identification process and the definition process.

Most investment appraisals are based on cash flows but there are other factors that may need to be included, such as:

-

Legal considerations – a project that enables an organisation to conform to new legislation may be compulsory if the organisation is to continue to operate. An appraisal based on the return on investment is therefore less appropriate.

-

Environmental impact – the effects of work on the natural environment are increasingly a factor when considering an investment. Environmental impact analysis of infrastructure work is written into legislation in many parts of the world.

-

Social impact – for charitable organisations, return on investment could be measured in non-financial terms such as ‘quality of life’ or even ‘lives saved’.

-

Operational benefits – these could include less tangible elements such as ‘increased customer satisfaction’, ‘higher staff morale’ or ‘competitive advantage’.

-

Risk – all organisations are subject to business and operational risk. An investment decision may be justified because it reduces risk.

Investment appraisal needs inputs from all these factors. During the identification process of a project or programme these inputs will be ‘top-down’, i.e. based on comparative or parametric estimating techniques. In the definition process they will be summaries of detailed delivery planning, i.e. bottom-up.

The first specific step is to collect the relevant information. Depending upon where in the life cycle this is being done it may require the creation of top-down data or the summarisation of bottom-up data. This should be done in conjunction with stakeholders to ensure that all relevant subjective, as well as objective, inputs have been captured.

Subjective dis-benefits are often the biggest point of disagreement amongst stakeholders. If a new railway line adversely affects a popular rural beauty spot, how is that compared to the economic benefit that the railway creates?

In cases like this the dis-benefit is entirely subjective and even the benefit is difficult to quantify making comparison very difficult.

The next step is to perform the appraisal using suitable techniques. Finally, the results of the appraisal are reported, usually in the form of a business case.

At the heart of an investment appraisal lies a comparison between investment and return. Any objective comparison requires both sides to be measured in the same units, i.e. cash. In many cases the investment side of the equation in projects, programmes and portfolios is easily quantified in terms of cash, with the exception of subjective dis-benefits.

The return can also usually be measured in terms of cash but subjective benefits can often be a significant component.

There are numerous techniques for investment appraisal and where there is a significant emphasis on subjective benefits, scoring methods may be most appropriate.

The simplest of the financial techniques is the payback method. This calculates the payback period, i.e. the time taken for the value attributable to benefits to equal the cost of the work. This is a relatively crude mechanism but can be useful for initial screening, especially when reviewing projects and programmes for inclusion in a portfolio.

A better way of comparing less complex investments is the accounting rate of return (ARR). This expresses the ‘profit’ as a percentage of the costs but has the disadvantage of not taking the timing of income and expenditure into account. This makes a significant difference on all but the shortest and most capital-intensive of projects.

Where there is a significant time difference between the expenditure and the consequent financial return, discounted cash flow techniques are more appropriate. The simplest of these is the calculation of net present value (NPV). This calculates the present value of all cash flows associated with an investment: the higher the NPV the better. A discount rate is used to show how the value of money decreases with time (assuming an inflationary environment).

The discount rate that gives an NPV of zero is called the internal rate of return (IRR). NPV and IRR can be used to compare alternative approaches in solutions development or a number of projects or programmes in the portfolio management process.

An example of the effect of whole-life costing would a nuclear power station. A full appraisal would include the cost of decommissioning the plant and disposing of waste as well the construction and operating costs.

When appraising capital-intensive work the full product life cycle may need to be considered because of the significant termination costs.

One of the biggest issues with investment appraisal is over-optimistic estimates of the value of benefits. Some appraisal approaches use an adjustment for optimism bias where opinions on benefit value are reduced before inclusion in a business case.

The potential for optimism is greatest when the benefits are difficult to quantify and assumptions have to be made about their value. The value of intangible benefits may be quantified by applying a series of assumptions. For example, work that improves staff morale may lead to lower staff turnover and reduced recruitment costs. The reduction in costs then constitutes the financial value of the benefit. Such assumptions need to be carefully documented and reviewed.

Benefits arising from organisational change can give rise to a significant proportion of intangible and non-financial benefits being included in an appraisal. Appraisals should not to be overly dependent on non-financial benefits, as anything can be justified through subjective views of value.

Projects, programmes and portfolios

All investment appraisal is based on the relationship between cost and benefit but many projects have no involvement in the benefits realisation process and are only concerned with delivering an output. If a project hands over an output to business-as-usual or a programme management team for subsequent benefits realisation, the project management team may have no responsibility for the initial investment appraisal. Even so, the project manager should be familiar with the investment appraisal in the business case and manage the project accordingly.

The project manager is usually given responsibility for maintaining the business case and updating the investment appraisal even if this was originally prepared by someone else.

Where the project delivers an output to a client under contract, the contracting project management team may perform a form of investment appraisal that balances the contractual costs and risks against the agreed price and payment terms as part of their own business case.

Programmes will have an overall business case but may also take responsibility for performing separate investment appraisals of component projects. The programme management team must set out standards for the appraisal of component projects and their associated benefits in a finance management plan. This needs to accommodate the fact that a single benefit may be derived from multiple outputs. The full value of that benefit cannot therefore be claimed by any one project.

Consistent and compatible techniques must be used across the programme so that individual project business cases can be aggregated and summarised in the tranche or programme business cases.

In portfolios the management process includes an activity where projects and programmes are selected for inclusion in the portfolio. In a structured portfolio, suggested projects and programmes should have a clear link to fulfilment of the strategic objectives covered by the portfolio. In a standard portfolio it will simply be a matter of whether the project or programme is worthwhile and within the constraints defined for the scope of the portfolio.

The portfolio management team must establish a system for capturing and screening ideas for new projects or programmes. This is where simpler techniques such as payback and ARR may be used. A criterion may be set that requires payback within the financial planning cycle. Any projects or programmes that do not provide payback in that period are discarded. As the higher-potential ideas are captured, they will be subject to more detailed appraisal.