General

Scope management identifies, defines and controls objectives, in the form of outputs, outcomes and benefits. Its goals are to:

- identify stakeholder wants and needs;

- specify outputs, outcomes and benefits that meet agreed requirements;

- maintain scope throughout the life cycle.

Scope is the totality of outputs, outcomes and benefits that should be delivered. The complexity of the scope is the main distinguishing factor between work that is managed as a project, a programme or a portfolio.

A key element in the identification process is to decide whether achievement of the objectives requires changes to business-as-usual.

The management of low level change may well be achievable using typical project governance structures. More extensive and complex change is an indicator that programme (or in some cases portfolio) governance structures are more appropriate.

The way in which scope is managed depends upon three things: the nature of the objectives (outputs, outcomes or benefits), the definability of the objectives and the complexity of the work.

The scope of a project will typically only include outputs but, where complexity is low, may be extended to cover benefits. The scope of a programme invariably covers benefits realisation and the resulting change management. The scope of a standard portfolio is defined by its component projects and programmes whereas the scope of a structured portfolio is defined by the strategic objectives it is designed to achieve.

Scope management is made up of five main areas that work in unison to identify, define and control the scope:

- Requirements management captures and analyses stakeholder views of the work’s objectives. Requirements are ‘solution-free’, i.e. they describe the stakeholders’ wants and needs but do not determine the outputs required to meet them.

- Solutions development takes the requirements and investigates how they may be met while providing the best return on investment.

- Benefits management takes requirements that have been expressed in terms of benefits and manages them through to their eventual delivery. Benefits management is usually dependent upon change management to convert outputs into outcomes and derive benefits from outcomes.

- Change control is a procedure that captures and assesses potential changes to scope. It ensures that only desirable, achievable and viable changes are made.

- Configuration management monitors and documents the development of products. It records approved changes and archival of superseded versions. The information in a configuration management system will help the assessment change requests.

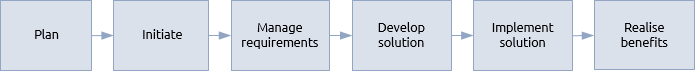

The way that these areas inter-relate varies considerably. A simple scope management procedure could take the following form (‘implement solution’ covers both change control and configuration management):

This describes a linear approach that is appropriate where a small number of outputs support a small number of benefits, i.e. a piece of work of low complexity that will probably be managed as a project.

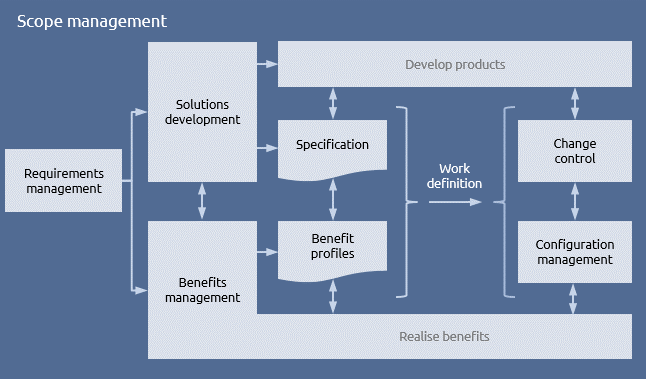

In a more extensive piece of work where multiple outputs and benefits have complex relationships, scope management integrates the procedures of its component functions.

Requirements management will always trigger solutions development, which designs the tangible outputs. If requirements have been defined in terms of benefits then the benefits management function will be triggered. Benefits rely on the implementation of outputs so solutions development and benefits management must initially work in parallel.

Once outputs have been documented in a specification and benefits have been defined in benefit profiles the work has a baseline for what must be delivered. This normally occurs at the end of the definition phase of the life cycle although some detail may be left for completion at the beginning of stages or tranches.

Definition of the work needed to deliver the specification and benefits is covered as part of schedule management. This work definition will be used to create models of the work that enable time scheduling, resource scheduling, budgeting and cost control.

Once work starts on the delivery phase of projects and programmes any changes to baseline scope must be subject to formal change control and recorded in configuration management along with the results of quality control.

The develop products process covers the conduct of the work that is entirely dependent on the technical content, whether it be construction, software development, pharmaceutical development or any other sector. The detail of this is outside the remit of P3 management except where it interfaces with scope management.

Benefits management continues beyond the production of the benefits profiles to cover the use of change management to realise benefits. This function can be described in a way that is sector-independent and is therefore deemed to be part of P3 management.

The degree to which detailed requirements and solutions can be predicted at the beginning of the project, programme or portfolio will influence how scope is managed.

The evolution of P3 terminology has created potential confusion in the terms ‘change control’ and ‘change management’.

Change control deals specifically with the control of potential changes to scope.

Change management covers the work involved in changing working practices in business-as-usual.

Where the objective is well understood and has a tangible output (e.g. in construction and engineering projects and programmes) it is usual to define the scope as accurately as possible in the definition phase. Change control then assesses all potential changes to scope, reduces cost escalation and maintains the viability of the business case.

It is also useful to define what is outside of scope to avoid misunderstandings. Clearly defining what is in and out of scope reduces risk and manages the expectations of all the key stakeholders.

Where the objective is less tangible or subject to significant change, e.g. business change or some IT systems, a more flexible approach to scope is needed. A parallel life cycle may be adopted and an agile approach where scope is iteratively refined throughout the delivery phase. This requires a careful approach to avoid escalating costs.

An important factor in managing the scope of work is to maximise value for money. The discipline of value management brings together an important set of procedures and techniques that operate throughout the six areas. It ensures that investment in a project, programme or portfolio is optimised for the potential return it can deliver.

Projects, programmes and portfolios

Once an output has been specified, work definition determines the individual activities that will be needed to create it and its component products. This information can be presented as a product breakdown structure (PBS) and/or a work breakdown structure (WBS).

Developing a breakdown structure is an iterative exercise. It will initially be done during the definition process in parallel with detailed planning for other aspects of the project (i.e. time and cost). These three elements of the triple constraint must be balanced, and this may require various adjustments to the detail of the PBS and WBS.

In traditional projects where there is a reasonably comprehensive specification of the output, the approved breakdown structure is baselined at the end of the definition process. The products in a PBS will become configuration items in a configuration management system, and any proposed changes of scope will go through a formal change control procedure.

The terminology of scope has become somewhat blurred in recent years. Praxis takes the following approach to establish some clarity:

- An objective can be an output, outcome or benefit.

- Most outputs are formally handed over from one party to another – in which case they may be referred to deliverables.

- A more complex output may be made up of multiple products, some of which may be deliverables in their own right.

- Some products will also be entered into a configuration management system and defined as configuration items.

- Products, groups of products and the work to produce them are collectively known as work packages.

Some projects use an agile approach where the scope baseline will initially comprise functional requirements rather than fully specified products. The products that fulfil these functions will be developed in iterations known as time boxes.

Programme requirements are typically described in terms of outcomes and benefits with the associated outputs being delivered by projects. The scope of a programme is therefore specified using a blueprint, benefit profiles and a list of component projects.

The relationship between outputs, outcomes and benefits is rarely one-to-one and there will be multiple dependencies between the outputs, outcomes and benefits. These interdependencies must be defined and documented. Effective solutions development, benefits management, change control and configuration management for the programme as a whole will all depend upon understanding these interdependencies.

The scope of a programme tends to be more fluid than that of a project. It is unlikely that solutions for all the projects within the programme can be identified at the outset and the business environment may change. A programme management team will have to manage evolving scope throughout the life cycle.

A standard portfolio is an accumulation of projects and programmes with unconnected objectives. The primary purpose of a standard portfolio is to create an infrastructure that implements consistent standards and makes optimum use of the organisation’s resources. Its scope is flexible and is simply the sum of the projects and programmes it contains.

A structured portfolio is defined by the strategic objectives of its host organisation that it is designed to satisfy. Its scope is the sum of the projects, programmes and change activity required to deliver those strategic objectives.

Scope management of a structured portfolio starts by identifying relevant projects and programmes. It’s likely that existing projects and programmes will initially be included, over the life of a portfolio, many ideas for projects and programmes will emerge and compete for inclusion. The scope is regularly reviewed and adjusted by the prioritisation and balancing activities in the portfolio management process. Eligibility criteria need to be established which may be expressed in terms such as required levels of return on investment or acceptable levels of risk.

The portfolio governance process should provide rules for bringing new proposals forward for review with the portfolio manager helping project and programme sponsors to shape their potential entry into the portfolio. While solutions development and benefits management are largely delegated to projects and programmes the portfolio co-ordination process will ensure that value is maximised.