Introduction

“All models are wrong, but some are useful” is a statement attributed to the statistician George Box although the basic principle was well known before, he summed it up so succinctly. Similarly, the French philosopher, Paul Valéry said “What is simple is always wrong. What is not is unusable.”

When Praxis uses the term ‘Project delivery’ it is referring collectively to the management of projects, programmes and portfolios.

The term ‘initiative’ is used collectively to refer to projects, programmes and portfolios.

The world of management theory is awash with simple models that are wrong but useful, because the complicated ones are unusable. Many of these are described in the Praxis Encyclopaedia. Although they are not ‘right’ insomuch as they accurately describe fundamental principles that apply in all situations, they help project managers build a mental picture of the project delivery landscape.

This begs the question, why create another model? To answer this, we need to explain why the Praxis Framework exists. The underlying objectives of Praxis are to:

1. Integrate the four elements of organisational project delivery (knowledge, method, competence and capability maturity) into a single, consistent framework.

2. Unify the many different flavours of project delivery into a single, adaptable framework.

3. Describe the components of the framework in concise, discrete elements and structure the content in an accessible and intuitive way.

4. Provide tools and techniques that support the practical application of the framework and make good practice an effective and efficient habit.

The purpose of the Praxis Delivery Model is primarily to achieve the second objective and create a foundation for the third. The model provides a basis for describing the rich and varied spectrum of project delivery while retaining terms and concepts that are in common use. We hope you find it sufficiently correct and simple enough to be truly useful.

The underlying model

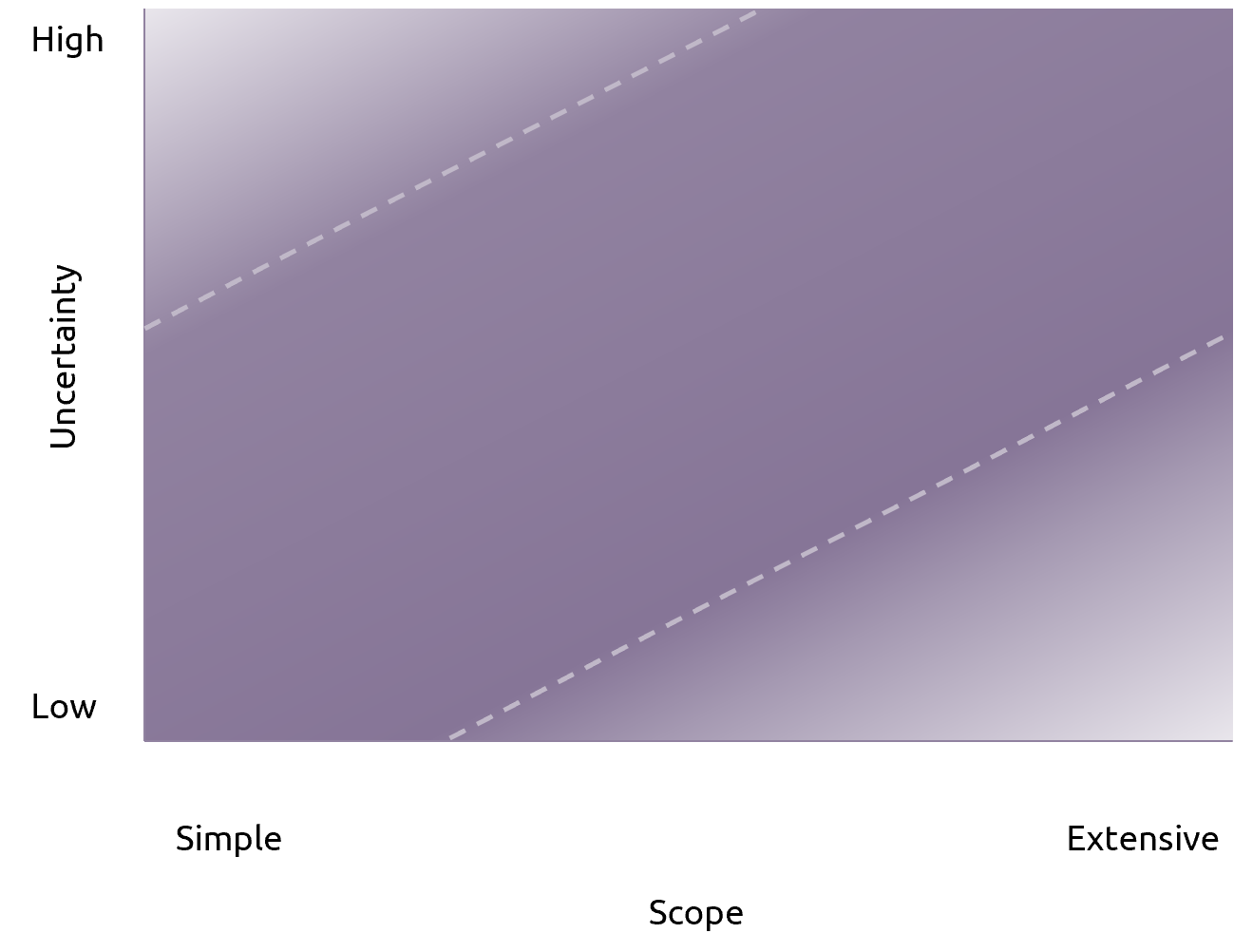

Like many models, the Praxis Delivery Model has two dimensions, in this case they are ‘scope’ and ‘uncertainty’. These axes are the most appropriate when describing the many different forms of governance and management involved in the diverse world of project delivery.

On that basis the first thing to clarify is what is meant by ‘scope’. Scope must have limits, otherwise the work is unmanageable. It should be clear what is included and what is not. Scope is everything that is included: the objectives, and the work required to deliver them.

The range of scope is a continuum from simple to extensive. It includes the breadth and depth of what is to be performed and delivered. For example, a simple initiative may only have one output to deliver while an extensive initiative may have multiple outputs that have many-to-many relationships with multiple benefits.

Uncertainty also has two elements: intrinsic (i.e. arising from the nature of the work) and extrinsic (i.e. arising from the world outside the boundaries of the work). It is also a continuum ranging from low to high.

The uncertainty of scope is intrinsic. It indicates how much is knowable about the scope at the outset. Building a house to a previously used layout has very low uncertainty while a manned mission to Mars has extremely high levels of uncertainty.

Extrinsic uncertainty is not inherently part of the work. For example, when working outside, we may be uncertain about how much bad weather will affect progress but this is not an inherent characteristic of the scope of work.

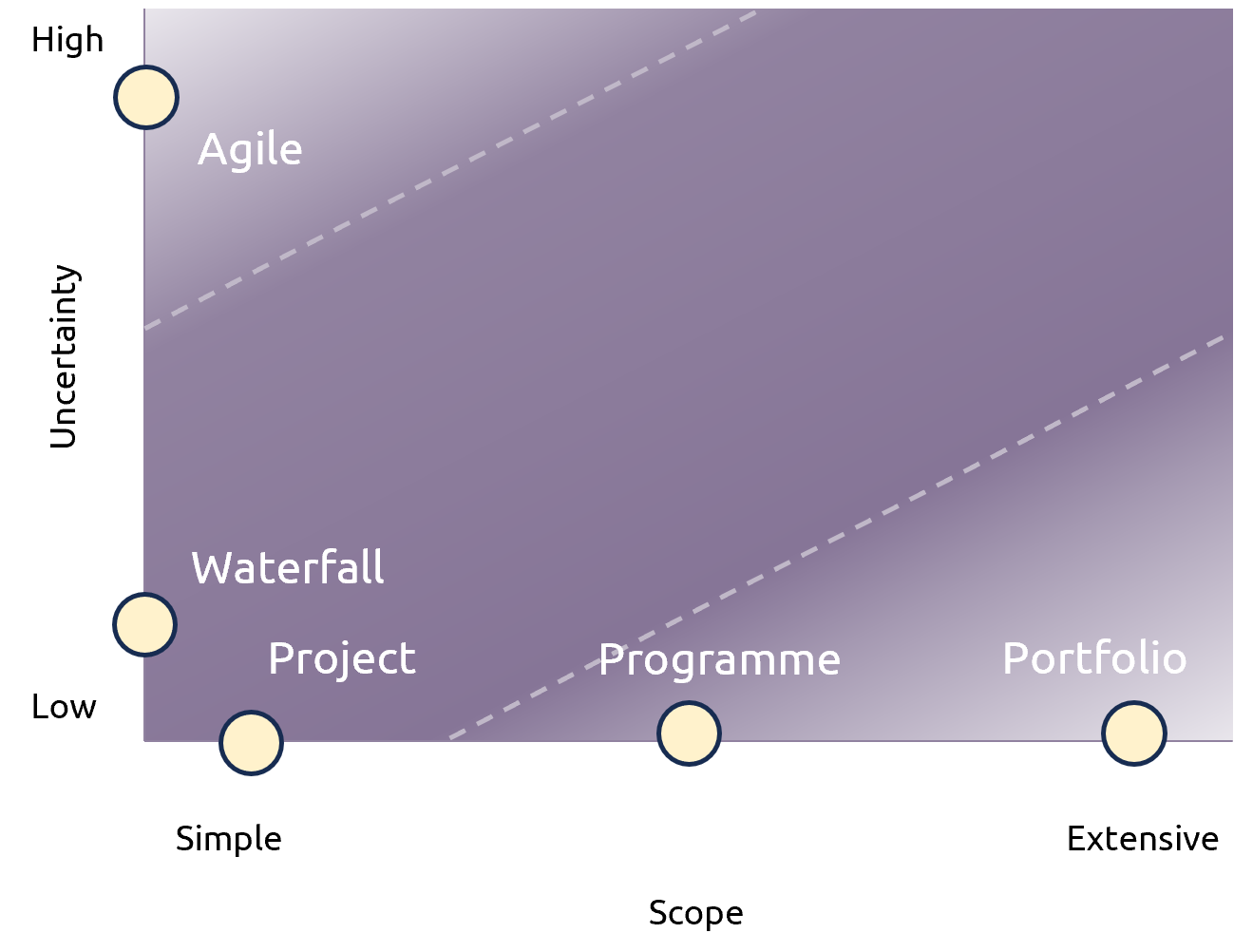

While scope and uncertainty are fundamental properties of an initiative, modern conventions of project delivery identify a number of paradigms.

On the scope axis these paradigms are projects, programmes and portfolios, with each term attempting to define a particular subset of the full continuum.

On the uncertainty axis the paradigms work slightly differently. Instead of describing the level of uncertainty, they describe an approach to managing it. The common terms are Agile (aimed at managing high uncertainty) and Waterfall (deemed to be appropriate for low uncertainty).

These narrow paradigms can be placed onto the model in a simple way to emphasise that they do not collectively represent the whole picture.

A more realistic approach to the horizontal scale is to show projects, programmes and portfolios as broad, overlapping approaches to governance or scope. When it comes to the uncertainty axis, it is better to do away with the terms agile and waterfall altogether and show that low uncertainty is managed with low levels of agility while high uncertainty is managed with high levels of agility (see Uncertainty and agility)

The shading of the model indicates that most projects, programmes and portfolios lie on a band from bottom left to top right. While some simple projects might be highly uncertain, these are rare. Similarly, while some extensive portfolios may have low levels of uncertainty (for example, a portfolio comprising only simple projects), this is less common.

Complexity

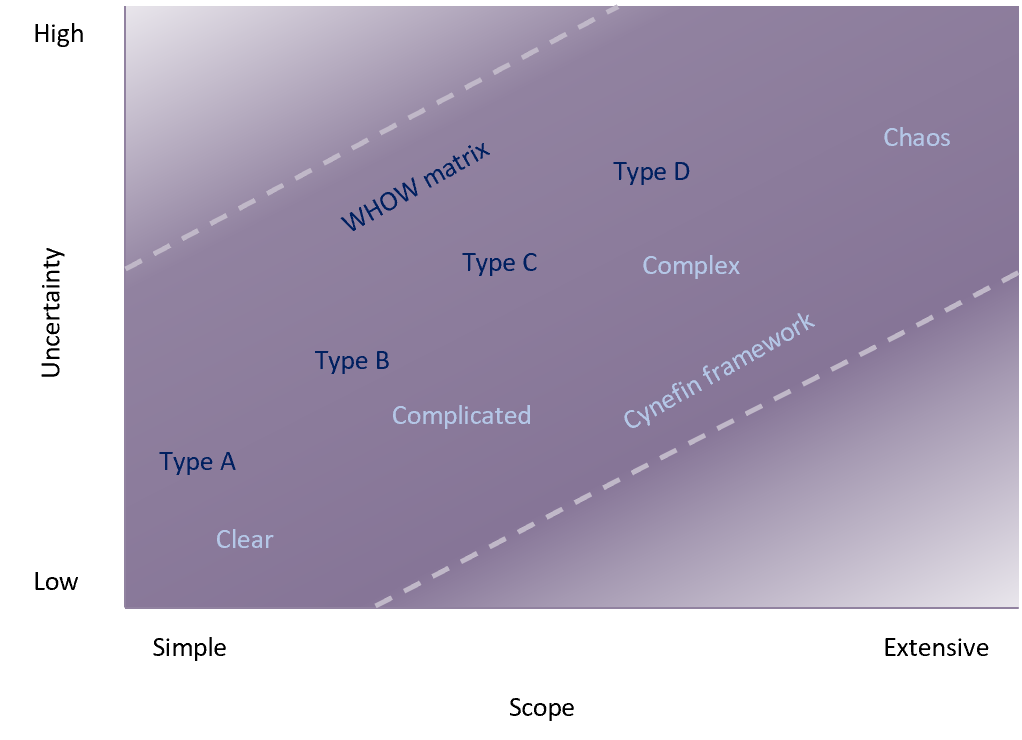

The combination of the uncertainty and scope axes typically creates complexity.

To be clear about complexity it’s worth making a comparison between complex and complicated. Projects and programmes are systems made up of components that are interconnected in different ways. As the system gets larger, the number of interconnections can increase exponentially, as do the system’s responses to inputs.

In a complicated system, the components and interconnections are ‘knowable’. This means that the way a system will respond to defined inputs can be determined.

In a complex system, the components and interconnections are ‘unknowable’. Exactly how the system will perform and behave in response to inputs is difficult to predict.

Of course, systems are often a combination of both. Some parts are complicated and some parts are complex. There may even be some parts that are clear and simple.

Complexity tends to increase from the bottom left of the model to the top right. This should be treated as indicative rather than an absolute relationship. It acts as a basic for understanding the different management styles required.

Applying the model

The model has three practical uses:

- As a basis for describing the application of functions and processes in the Praxis Framework

- As common ground to explain related models.

- As a reference point for tools and techniques.

This positions the model as the cornerstone of the Praxis Framework. Everything else is derived from this model. As a result, Praxis is able to address the common categories of project, programme, portfolio, agile and waterfall in a single integrated framework. It is up to a competent project delivery manager to decide where to place the emphasis and how to draw on a combination of these categories to effectively manage their specific initiative.

As a basis for describing functions and processes

The Knowledge section of Praxis is made up of functions, such as stakeholder management, risk management and benefits management. These are the functions that collectively comprise the discipline of P3 management.

The Method section is made up of processes such as identifying a project or programme and delivering a project or programme. These are the processes that describe the management of life cycle phases.

While these functions and processes are common throughout project delivery, the way they are applied depends on the extent and uncertainty of the work being managed.

Using the delivery model, the descriptions of the functions and processes can explain common principles and then go on to discuss their application in different contexts based on scope and uncertainty.

Common ground to explain other models

Two models that are very useful for understanding the progression through the model are the WHOW matrix and the Cynefin Framework. Both of these are summarised in the Praxis Framework encyclopaedia.

The WHOW matrix addresses the fact that intrinsic uncertainty is made up of two components: uncertainty about how to define objectives and uncertainty about how to achieve them. It focuses on how these two components of uncertainty affect the life cycle.

The Cynefin Framework is a ‘sense-making’ framework for dealing with systems with differing degrees of complexity. For example, it would indicate that the best approach to the simple project in the bottom left corner would be to ‘Sense, Categorise and Respond’ and use ‘best practice’.

Whereas, were you have an extensive portfolio of highly uncertain projects and programmes in the top right corner, you need to ‘Act, Sense and Respond’ using ‘Novel practices’.

Superimposing these models on the Praxis model provides a catalyst for seeing how knowledge gained from both these models can be combined.

A reference point for tools and techniques

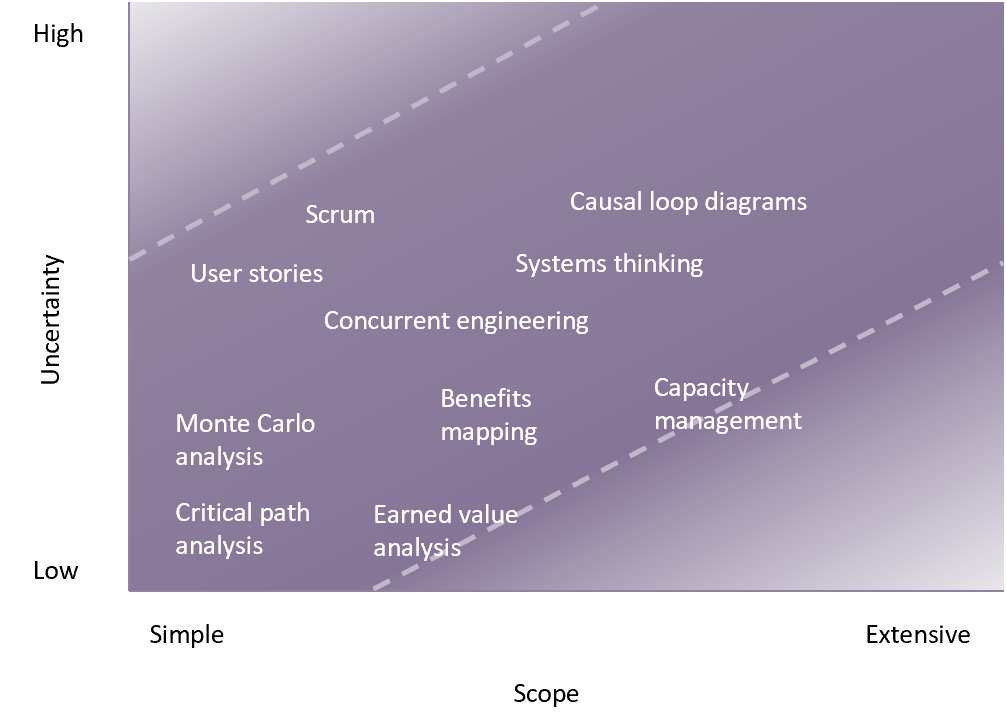

Different tools and techniques have different strengths and weaknesses in relation to the uncertainty and extent of the scope. This is not an exact relationship, the positioning of the various tools and techniques on the diagram below is purely indicative and used as an aid to understanding where and how different tools and techniques are relatively best applied.

For example, Critical Path Scheduling is ideal for projects with low uncertainty. If there is particular uncertainty in estimating the activities, then something like Monte Carlo analysis can be used.

Where there is uncertainty about how to achieve objectives but there is a high cost of change once delivery is under way (e.g. physical projects like a communications satellite), then Concurrent Engineering is useful. Where there is high uncertainty about the finished outputs, but the cost of change is much lower, then agile development approaches can be the best way to work, perhaps using scrum or kanban.

As the scope of the work becomes more extensive and more uncertain, more effort needs to be put into understanding the complex system that the project is creating or changing. That’s when, for example, techniques like Systems Thinking come into their own using tools such as Causal Loop Diagrams.

Summary

Project delivery is a very diverse discipline that ranges from the small and simple to the large and complex. Scope and uncertainty are useful axes that create a canvas on which different aspects of project delivery can be framed.

Praxis Framework uses this model to introduce the many contexts in which its functions and processes may be applied and emphasise that competent and effective project delivery depends upon matching the approach to the context, rather than getting stuck in the application of narrow paradigms.