First published in Project Manager Today magazine

In these days of new technology and ever more powerful computers it is easy to overlook the basics of business-led project management. In this, the first of a series articles, drawn from his best selling book, The Project Workout, Robert Buttrick reminds us of the fundamentals of business-led project management. Projects are about change.

Whether this is for your customers, as external projects, or for yourselves, as internal projects, the desired outcome is the same: do them well and your organisation will thrive.

This first article concentrates on the business drivers for any project. It looks at ensuring the right

projects are initiated to realise the benefits the business needs.

Make sure your projects are driven by benefits which support your strategy.

In simple terms, if you have no strategy, how do you know what you intend to do will benefit your organisation?

When two radically different projects appear to have the same benefits, how do you choose between them? All companies have to make choices at some point in time. Usually there is no shortage of good ideas for new projects but frequently there is a shortage of money and resources to undertake them. If you are to have an effective organisation, screening out the unwanted or sub-optimal projects as soon as possible is key.

At the very start of a project, there is usually insufficient information of a financial nature to make a decision regarding the viability of project. You should, however, be able to assess strategic fit from the beginning. Not surprisingly, those companies with clear strategies are able to screen far more effectively than those that don’t. Strategic fit is often assessed by means of simple questions such as:

- Will the results of this project help ensure long-term relationships with our customers?

- Will this new product ensure we maintain our leadership position?

- Will this operational method ensure that overall operating costs continue to reduce?

The less clear your strategy, the more likely poor projects are to pass such initial screening. In such cases there will be more projects competing for scarce resources, resulting in your organisation losing focus and jeopardising its overall performance. Remember, a clear strategy is also useless if you have not communicated it in a way managers can apply to their day-to-day decisions.

Address and revalidate the marketing commercial operational and technical viability of the project throughout its life

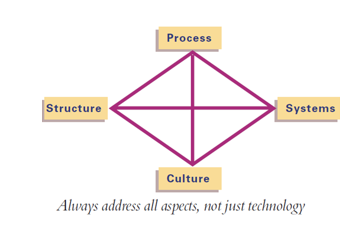

Projects are not just about technology. I often argue there is no such thing as an IT project – there are just projects that have a high IT component! In practice, many things need to happen across an organisation before any benefit can be realised; these often revolve around training, operational processes and the deployment of equipment and people.

Projects are not just about technology. I often argue there is no such thing as an IT project – there are just projects that have a high IT component! In practice, many things need to happen across an organisation before any benefit can be realised; these often revolve around training, operational processes and the deployment of equipment and people.

A project must include all aspects, which are prerequisite to benefits realisation, regardless of whether the skills or resources come from inside or outside the organisation. It is pointless, for example, having an excellent technological product which has no adequate marketing rationale relating to it and cannot be economically produced.

Nor is it sensible to develop a superb new staff appraisal system if there are no processes and administration to make it happen. I even came across a ‘project’ where the necessary power and air conditioning upgrades relating to a computer hardware installation were considered ‘outside the scope of the project‘ as they were not IT! And yet without this, the computer equipment simply would not work.

Projects always require a mix of skills, organisation, people, processes and technology: no single one of these aspects should be allowed to proceed at a greater pace than the others. As the project moves forward the level of knowledge increases and the overall level of risk should decrease. At particular points in the project, we should confirm the project is still viable:

- Is the project still needed?

- Are the benefits still there for the taking?

- Is there still a demand for the outputs?

- Can the technology be made to work?

- Have we the operational resource to manage the outputs?

- Can we maintain this at an economically low cost?

No single aspect should be allowed to dominate; we are, after all, looking at business benefits, not the prowess of individual departments or even individuals within a department.

Coupled with this, every organisation must have the ability to terminate projects. There is little point in reviewing the overall viability of a project, if there is no will, on behalf of the decision-makers, to accept termination as an option. It’s a tough world, requiring tough decisions, but we might as well make sure they really do benefit the business!

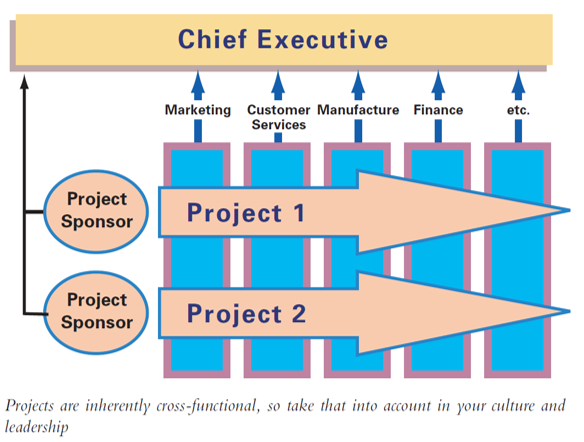

Break down functional boundaries by using cross-functional teams

We have seen above that a business-led project requires resources and skills from across the whole company. It therefore stands to reason that any organisation which is serious about change must be able to work in crossfunctional teams, drawing people from wherever is necessary.

Running projects in functional silos and ‘coordinating’ between them is always far slower, produces less satisfactory results and increases the likelihood of errors and conflict. The companies which recognise this have working practices which encourage lateral communication, rather than hierarchical communication, thrive better than those still stuck in the functional hierarchies of the 1970s.

In some cases, cross-functional cooperation goes as far as removing staff from their own departmental locations

and relocating them in project team work spaces. In others, departmental staff who frequently work together are located as close as is practical in the company’s premises. Generally, the closer people work, the better they perform. Unfortunately, close working proximity is not always a practical solution in these days of global projects.

However, frequent meetings and good communication can compensate for a lack of physical proximity. This can be encouraged by using techniques such as video-conferencing, audioconferencing and shared project ‘web spaces’ which include discussion groups and chat rooms where everything on the project is available to all the team, anytime, night or day. For the first time in history, projects can continue while one half of the team is in bed in Europe and the rest are working in the Far East. Cross-functional team working, however, is not the only facet.

Direction and decision-making also have to be on a cross-functional basis.There is little point in people working in teams across the whole company if directors and decision makers in different parts of the company give conflicting instructions, make contradictory decisions or are working to different priorities or agenda. For those companies who are still tied to the functional hierarchies, a movement to cross-functional decision making can be very difficult. In practice, this can mean very senior people giving up some personal authority (and often perceived ‘face’) either to another individual or body with accountabilities to direct the work, in the best interests of the company as a whole.

Another requirement of cross-functional working is to ensure both corporate and individual objectives are not deliberately or accidentally placed in conflict. For example, it is not uncommon to find individuals on the same project team receiving radically different bonuses which are based on departmental performance rather than project performance. There is nothing more divisive than the unfairness relating to poorly structured reward systems. It is also not uncommon to find that key performance indicators for departments conflict with those required for projects or, indeed, with the needs of the overall company.

In complex organisations it is obvious the best solution for the business as a whole may not necessarily be the best solution for the individual parts of the business. The more functional an organisation, the more difficult it is to implement effective project management and thereby promote truly breakthrough change. This is because project management by its nature must cross functional boundaries.

To make project management succeed, the balance of power usually needs to be tipped towards project or cross-functional axis away from the line management and this requires a new type of manager, with a new set of accountabilities.

Incorporate selected users and customers into the project to understand the current and future needs

The involvement of stakeholders in a project is vital: but who are they? Stakeholders can mean the project team, customers, unions, operators of whatever is produced, senior management or even shareholders. Whoever they are, it is usually better to engage them as early as possible in the project. Engaging stakeholders early is a powerful mover for change, whereas ignoring them is a recipe for failure.

When viewed from an individual stakeholder’s viewpoint, your project may be just one more ‘thing’ they have to cope with as well as fulfilling their own duties on meeting their own objectives. It may even appear irrelevant or regressive to them. So why should they bother to co-operate? You don’t always need their undying commitment, often ‘consent’ is enough. If the stakeholders’ consent is required to make things happen, you ignore them at your peril! Nevertheless, you must ensure you use stakeholders effectively.

For instance, most car manufacturers would not ask the customer what the body shape for a car, to be produced in 2020, would look like. They have visionaries to design such things. They may, however, use customer focus groups to assess the features of the car that will be desirable and useful. (I am reliably informed by Bill Bryson that every American car has far more cup holders than seats!)

Pause for thought . . . the blockers to achieving project excellence

Concentrating on ‘what’ at the expense of ‘why’. Be absolutely clear on why you are undertaking a project and who is accountable for directing it. If you don’t, attention will focus on what is being produced, regardless of the business need. When prioritising, don’t prioritise projects, prioritise benefits!

Functional thinking.

Not taking the helicopter, companywide perspective. This often happens when executives’ incentives are tied more to the performance of their departments than to the performance of the company or where such targets conflict.

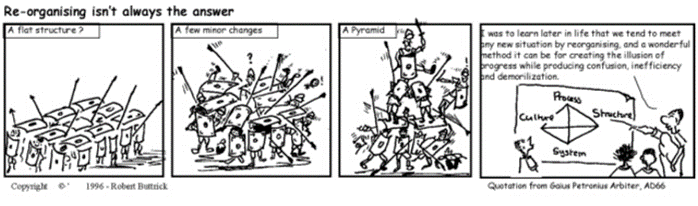

Reorganising.

Tinkering with or even totally rebuilding a company’s functional hierarchy is rarely a solution to corporate under-performance. It usually confuses more than it clarifies. Unless cross-functional processes are realigned at the same time, performance will deteriorate on both day-to-day operations and (especially) on projects.

Read the second article in this series

© Robert Buttrick