This is the second of three articles on effort estimating. In the first, I focused on definitions since I find that many people use terms such as estimate and budget as synonyms when, in fact, they are very different. Here is a brief recap of the key definitions:

Estimate. An informed assessment of an uncertain event. Informed means that you have an identified basis for the estimate. Uncertain recognizes that multiple outcomes are possible.

Effort. An expenditure of physical or mental effort on the part of a project team member. Effort is normally measured in terms of person hours.

Budget. A management metric that is usually derived from the estimate of the relevant work.

Baseline. A time-phased budget that has received all necessary approvals.

A simple example

Let’s start with a simple example to build a conceptual foundation. Later, we’ll use these concepts to help deal with more difficult effort estimating challenges.

It may seem obvious, but the first requirement for developing an effort estimate is to know what you are estimating. For now, let’s assume that you have been asked to estimate how much effort (how much of your own time) is likely to be required to paint your bedroom.

Although this is a fairly small activity, it is still one with a significant amount of uncertainty:

- Do you have to paint the ceiling and the woodwork, or just the walls?

- Are there windows to be painted?

- Do they have mullions that also have to be painted?

- Is there furniture in the room?

- Is moving it or covering it part of “painting the room”?

- Is choosing the color part of this activity?

- What about going to the store to buy the paint?

- How many coats are needed?

- Is there any special finishing involved (like marbleizing)?

- Do you have all the equipment you need?

- If not, is obtaining it in or out of scope?

If you don’t know the answers to these questions, you have a five basic choices. You can:

-

Decline to deliver an effort estimate for doing the work and instead, deliver an effort estimate for figuring out how much effort will be required to paint the room.

-

Deliver an estimate with a substantial contingency included 'just in case'.

-

Make some assumptions about the answers to these questions and estimate the amount of effort based on those assumptions.

-

Try to reduce the uncertainty by getting answers to the questions before preparing an effort estimate. This option is basically a variant on item #1 above.

-

Paint a small portion of one wall and use that experience to forecast a total for the whole room.

Any of these approaches is acceptable as long as your stakeholders know which approach you are using.

Most of the time, you will use some combination of these options. You will make some reasonable assumptions (and you will always document all of your assumptions). You will ask some questions. Then you will apply your best judgment.

Range estimates

You can improve your best judgment by making range estimates. How does a range estimate work? In its simplest form, you estimate a low value and a high value for the amount of effort that you think you are likely to need. For example, in the case of painting your bedroom, and assuming that the scope is limited to applying one coat of paint to the walls, you might estimate 2-3 hours of effort.

[Note that we are only talking about effort here, not duration or elapsed time. Those 2-3 hours might be done continuously, or might be spread out over a couple of days or even weeks. Nor are we yet addressing costs or prices.]

The fundamental concept behind range estimating is that you don’t need to know the exact amount of effort that is required. You do need to know that it isn’t going to take a full day out of your schedule. You do need to know that this isn’t a trivial activity that can be completed in a few minutes. As long as the actual result is around 2 or 3 hours, you have made a good estimate.

In fact, even when the actual result falls outside of your estimate's range, you still made a good estimate since it was the best estimate that you could make given what you knew at the time. In addition, you can learn from this estimate variance (an estimate variance is an actual result that falls outside the predicted range; it's not the same as a budget variance) and use that learning to try to improve your future effort estimates.

Using range estimates takes much of the pain out of the effort estimating process. If you are accustomed to single point estimates (see below), it can be very difficult to choose between 2 hours and 3 hours. Even quoting an estimate of 2.5 hours can be gut-wrenching because you know that it might take more or less than that amount. Using range estimates allows you to operate under uncertainty.

Single point estimates

Single point estimates are the devil’s workshop. They are pure evil. Don’t ever offer a single point estimate to anyone for any reason. If your boss insists on a single point estimate, they are most likely looking for an effort budget, not an effort estimate. There’s no problem with giving them an effort budget, but you really should share your estimate with them as well so that they understand how much confidence you have in the reliability of that budget number. The conversation might go something like this:

Boss: "How long will it take to paint that room?"

You: "We have estimated 2-3 hours of effort for one coat of paint."

Boss: "I need one number to get approval."

You: "We’re planning to budget 2.75 hours of effort to be on the safe side."

Three-point range estimates

You can improve your judgment still further by making three-point range estimates. In addition to the high and low values of a simple range estimate, you add an assessment of the most likely in-between result.

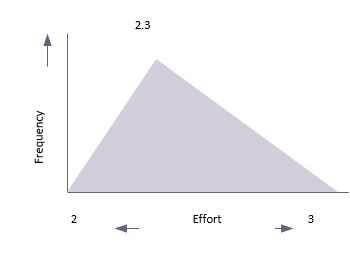

Let’s say, for example, that you are living in the world of Groundhog Day such that you can paint your room 100 times and keep records of how much effort it actually took. You discover that you never spent less than 2 hours and never more than 3. You also discover that your actual results produced a triangular distribution with a peak at 2.3 hours.

Based on the availability of this actual, historical information, you would estimate the amount of effort required to paint a similarly sized bedroom as follows:

Most likely: 2.3 hours

Optimistic: 2 hours

Pessimistic: 3 hours

I understand that you will seldom if ever have such wonderful, perfect historical information to base your estimates on, but the great thing about range estimating is that you don’t need perfect data. As long as the three-point range estimate is reasonable, errors are likely to balance out over the course of the project.

Even in this case, with perfect data, you still don’t know how exactly how much effort will be required for the next time you paint your bedroom. It might be 2.5 hours; it might be 3.75 hours. Doesn’t matter. What is important is that you have estimates that are reasonable; that you have estimates that will allow you to manage the project effectively.

Preparing three-point range estimates

The mechanics of preparing three-point range estimates, particularly if you are working with team members who have never used the technique before, are important.

Working one-on-one. Let’s again start with a simple case where you need an effort estimate from an individual team member regarding how much of their effort is likely to be required to complete a specific activity. The first step is to make certain that both of you have a common understanding of words like “estimate” and “result.” Do your best to keep your language consistent, even if you feel a little awkward.

For example, it is always tempting to say something like “how long do you think this will take?” This question is likely to produce a duration estimate rather than an effort estimate. Try to remember to ask “how much of your time do you think this activity will take?”

Begin the discussion with a review of the work to be done to ensure that both you and your team member have a common understanding of the work. If there are unknowns, decide how to handle them - make assumptions, go get answers, whatever.

Once you have a reasonable level of agreement, ask the individual for their effort estimate of the most likely result. I tend to use words like, “if these assumptions turn out to be true, how much of your time do you think this work is likely to take?” After they’ve answered that question, I ask, “if every thing goes well, if you get very lucky with this activity, and still using the same assumptions, how much of your effort do you think this activity will take?” Then I use similar language to obtain a pessimistic effort estimate.

Understand that the first few conversations with any given individual are unlikely to go smoothly. They may generate additional questions or ask you to make additional assumptions at any point during the conversation. Fine. Let them. Help them climb the learning curve.

My experience is that it takes most people 3-5 iterations to get comfortable with the process. After that, they’ll start giving you three-point effort estimates automatically.

Feel free to challenge their effort estimates, but do so constructively by asking clarifying questions. Do not cast aspersions on their estimates. If the two of you differ, the most likely explanation is that your understanding of the work differs. Concentrate on identifying and resolving those differences.

It also seems to be important to start by asking for the most likely result, then the optimistic, and then the pessimistic. I don’t know why, but this sequence seems to work best.

Working with a group. Most of your estimates will not be developed one-on-one, but rather will be developed by small groups as part of a team planning process. The basic process remains the same for these small groups:

- Review and agree on the work to be done.

- Document the assumptions.

- Develop three-point range estimates starting with the most likely result.

Even when some of the group members don’t have deep expertise in the project’s work, their presence can help to surface unstated assumptions and to build team-wide commitment to and understanding of the effort estimates.

Other approaches to three-point range estimates. Some project managers try to expedite the development of a three-point range estimate by asking for only two numbers—the most likely and some form of variance (e.g., “10 hours, plus or minus 2”). While this statement equates to a three-point range estimate of 8, 10, and 12, in my experience, it lacks the richness of my suggested process—it doesn’t seem to generate the same degree of thoughtfulness from the estimator.

Too much time?

I am convinced that the thinking process and the conversations that support three-point range estimating contribute to the development of more accurate effort estimates. Short-circuiting the process may appear to save time, but this is a false economy.

My experience is that developing three-point range estimates of effort almost always takes less time than developing single-point estimates because the process eliminates the posturing and gamesmanship that often delays the estimating process. I’ve had teams in my project management training courses spend less than an hour to develop an estimate for a 4,000 hour project - an estimate that later proved highly accurate.

A recent client spent less than a day to discover that a mission-critical, multi-million dollar new product development project was going to be eight months late. An investment of something less than $10,000 is expected to return in excess of $10,000,000. Time spent estimating is not a cost, it is cheap insurance.

In the last article of this series, I’ll cover some of the more difficult challenges of effort estimating on projects: what to do when management thinks it should take less, using range estimates with project management software, how to deal with the natural (and normal) biases of the estimators, and how to use some basic, simple statistical methods to create an effort estimate for the whole project.