First published in Project Manager Today magazine

Robert Buttrick’s third article, drawn from his best selling book, The Project Workout, takes us back to the fundamentals of business-led project management, looking at why we need a staged approach to managing projects.

Place high emphasis on the early stages of the project

A Finnish company told me: ‘Skipping the first stage is a driver for failure’. Both research and observation have shown that paying attention to the investigative stages of a project pays dividends. One American company found that 40% to 50% of the project timescale could effectively be spent on investigations before any deliverable is finally built. Not only that, they found such attention to the investigative stages made final delivery much quicker and more reliable.

Good investigative work means clearer objectives and plans; work spent on this is rarely wasted. Decisions taken in the early stages of a project can have a far-reaching effect on the outcome. By choosing alternative solutions and approaches to projects, it is possible to double, or even treble, the benefits, cut costs by a fraction and slash delivery time by months.

However, once your plan is set and your approach has been defined, the opportunities for improvement are very much smaller. In fact, you usually find there is more ‘down-side’ than ‘upside’ as projects usually go worse than expected because of the optimism associated with most plans which have been set within a business environment of ‘give me the fastest and cheapest solution - NOW’.

Good up-front definition reduces the likelihood of changes: most changes on projects result from misunderstandings, misinformation or lack of definition from work done in the early stages. The faster you move through these, the more likely you are to store up problems for the future. The further you are into a project, the more costly changes become. Despite all this received wisdom, there often pressure (for what superficially appear to be all the right commercial reasons) from senior management for people to skip investigative and planning work and ‘get on with the real work’ as soon as possible.

Companies who have a more mature approach to the management of change, have often learned, by hard experience, that they can’t move any faster by missing out essential work. They know skipping investigative stages leads to commercial failure, and whenever they have tried this for the sake of speed, they have always paid the penalty in higher operating costs, reduced revenues and dissatisfied customers and employees.

Build the business case into the company’s forward plan as soon as the project has been formally agreed

In a business-led environment, projects are about creating your ‘company of tomorrow’. Projects are the vehicles for creating future change and often form the basis of future revenue generation. It is therefore essential the company knows which projects it is undertaking and how they fit into the wider corporate objectives. This was discussed in the previous article when we looked at strategic fit.

Taking this one step further, it is vital for the company, not only to see the list of projects they are undertaking, but also they need to see how each is contributing to the cost base of the company and to its revenue generation.

It is for this reason the costs and benefits resulting from the business case in each project need to be built into the business plan as soon as project case is proven. Unless this is done, the business leaders will have no idea how they will fill the gap between where we are now and where we want to be in the future. They will also find it impossible to prioritise projects as they will have no basis on which to make the selection, even if their strategy is clear.

Close the project formally to build a bridge the future, to learn any lessons and to ensure a clean handover

If you are in an organisation with tight margins, closing projects as soon as they are finished is a ‘nobrainer’.

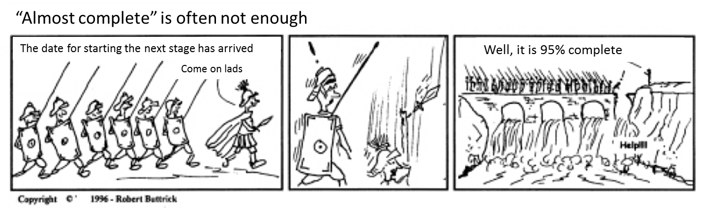

Such companies simply haven’t the luxury of wasting money by tinkering with project deliverables they have already completed. Tinkering with that final deliverable and polishing the final output is not an option for them.

For other industries, operating under a strict regulatory environment (for example aerospace), the concept of not having formal project closure is again unthinkable. They are required to keep full records of every step of the development of a new aircraft and each of its components together with the testing certificates. Not to have full records on these critical components in times of need is unthinkable. And yet, project closure is something many organisations ignore. The project team move rapidly onto the ‘new’ leaving the ‘old’ not quite finished.

Companies with a mature outlook on project management all have a formal closure procedure. This usually takes the form of a closure report highlighting outstanding issues, ensuring explicit hand-over of accountabilities and making it crystal clear, to those who need to know, that the project is finished.

Another reason for closure is to learn the lessons of the past and make sure they can be applied in the future. This can be a vital time for collecting the views and opinions of those engaged on the project to see how the methods, practices, relationships and systems work towards helping people deliver the results.

One final thought; if you don’t have project closure and you keep a list of the projects you are doing (a project register), your list will grow longer and longer and longer and longer......

Pause for thought ... the blockers to achieving project excellence

A project (or programme) should be defined in a ‘Business case’ (including a project definition). This will define why you are undertaking the project, what needs to be done, by whom, when and how. It applies solely to the ‘chunk of change’ under consideration. If your company has a coherent ‘Business plan’, it should be relatively easy to relate the project’s Business case to it.

However, if business planning is weak in your organisation, you will find projects increasingly difficult to justify and in the extreme, the business case will become a lengthy surrogate for the (missing) business plan. So ... don’t blame the ‘Business case’ for a lack of a ‘Business plan’!

Executive’s pet projects

Have no exceptions - if a senior executive’s project is really so good, it should stand up to the scrutiny that all the others go through and will also need the same level of management effort. He or she may have the helicopter view, but it may also be a case of head in the clouds.

Read the last article in this series

© Robert Buttrick