First published in Project Manager Today magazine

Robert Buttrick’s final article, drawn from his best selling book, The Project Workout, takes us back to the fundamentals of business-led project management, looking at why we need a staged approach to managing projects.

Organise your resources to support both your projects and your day-to-day workload

The assignment of resources to projects is something most companies have still not got right. In many companies, internal projects are resourced by people who both work on the day-to-day processes within the

company and have a role to play in projects.

The challenge has always been how to deploy these resources effectively such that neither the business of today nor the business of tomorrow suffers. Basically, there are two extreme approaches which can be taken.

The first approach is to ‘separate’ your resources. That is, apply dedicated resources to each type of project, say, aligned around a business unit, and take this principle as deep into the company as possible. In other words, to organise your functional structure to ensure the teams and departments are arranged such that they can be readily deployed into project teams for the particular type of project they are set up for. This approach has a number of advantages.

Potential conflicts are limited and decision making more localised - local decisionmaking is usually far quicker. In fact, the deeper you take this approach, the more localised (and hence quicker) your decision making can be as you have fewer people to consult and engage. There are, however, two major disadvantages:

-

The first is that by building this into your functional structure and head count, you actually limit your flexibility to react to emerging market needs and business imperatives. You’ll have to continually reorganise and resize your resource pools to meet demand and any other challenges in the marketplace. In a fast moving industry, this may mean you have the right number of people in the organisation but they may be in the wrong place! At worst, it will lead to continuous, expensive and damaging reorganisations.

-

If your organisation is very interdependent across its functions or business units, the scope for localising project resources is very limited and this approach to resource management will not deal with the more far reaching business change projects, only local ones.

The second approach is to have staff organised into resource pools based on their technical knowledge. Most consulting organisations follow this approach. Any individual could be working on any number of projects in a week and there may be many hundreds of projects in progress at any point in time. It is very effective, conceptually simple and totally flexible. The need for major reorganisation is less frequent.

Unfortunately, it is also the most difficult to implement in an organisation which has a strong functional management bias. As we learned in the first article, functionalhierarchies tend to find cross-functional working and decision-making extremely difficult.

Whatever approach you choose to take, it is vital to make sure your resource management, accounting and project systems are all able to support management reporting on both functional and project axis.

Build excellence in project management techniques controls across the company

The last learning point in this series of articles is perhaps surprising! Haven’t we been talking about project management? Then why is project management just one out of ten fundamentals we need to apply? If they followed the nine principles we have discussed so far, companies would be sure that the projects they are undertaking will produce what they need in pursuit of their objectives.

They would also have the right people engaged and the scope correctly bounded. But, to make it happen on the ground, a wide range of project management techniques needs to be applied. Project management techniques include planning, risk management, issue management and change management. ‘Planning’ includes benefits, costs, resources and schedule. All of this is done in an environment of assumptions, constraints and risk.

Planning as a discipline is essential. If you have no plan, terms like ‘early’, ‘late’ or ‘on time’ have no real meaning. Planning needsto be holistic, covering all aspects (cost, benefits, resources, quality) and not just schedule. It is also far too important to delegate to junior members of the project team.

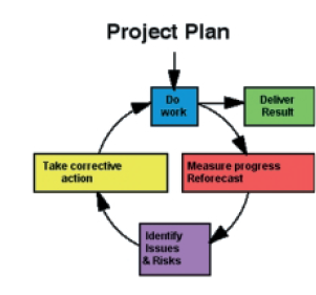

A project plan is, in fact, a model of what is likely to happen. Together with risk management, planning enables a project manager to understand the different futures that may lie ahead. He or she is able to model ‘what if ’ scenarios and define an approach to avoid the major pitfalls and risks.

Risk management is often quoted as being the most important of the project management tools. It is vital to take risk into account when producing a project plan and to keep revisiting the risk environment throughout the life of the project. Projects are inherently risky. But in business-led projects, it is not only the risks to the project deliverables we must consider but, more importantly, the risks to the benefits. These latter risks may dwarf all other deliverable related risks. Analysis and planning around risk need to be undertaken in the investigative stages and the approaches firmly built into the plan.

Despite excellent planning and risk management things will go wrong! Unforeseen issues will arise and they will need to be addressed. These, if not resolved, may threaten the entire success of project.

Monitoring and forecasting against the agreed plan will ensure that many events do not take those involved in the project by surprise. It should always focus more on the future than on what has already happened.

A project manager can only influence the future; the past is finished. Similarly, completion of activities so far is only evidence that progress has been made, not necessarily an indication that progress will continue to be made. A project manager should be continually checking to see that the plan is still fit for purpose and likely to realise the benefits it was set up to achieve.

A project manager can only influence the future; the past is finished. Similarly, completion of activities so far is only evidence that progress has been made, not necessarily an indication that progress will continue to be made. A project manager should be continually checking to see that the plan is still fit for purpose and likely to realise the benefits it was set up to achieve.

Ultimately some issues cannot be resolved without some redefinition of the project. It may require a scope change, an extension of time or additional funds. In such circumstances, change control comes in to play. Change control ensures only changes which are beneficial to the business are actually put into play and the project is not derailed by bright ideas or good intentions.

Changes are a fact of life and cannot be avoided, but preventing negative change is possible. In some circumstances, the right decision is to terminate the project - the ultimate change!

Many companies, which have been aiming to realise the benefits of business-led project management, have concentrated solely on project management techniques and training: they have been disappointed in the results. This is because they need to apply the other nine lessons and ensure the leadership of the organisation promotes a culture which fosters cross-company working, decision making and collaboration. Without these, even the best project manager, using the best techniques, will find it very hard to succeed.

Pause for thought ... the blockers to achieving project excellence

Ignoring the risks

Risks don’t go away if you ignore them. In fact, they grow. So acknowledge them and manage them. Also, whether you are a project manager or a decision maker, your actions must take into account the risks.

Untested assumptions

All projects are built on a mountain of assumptions. Some of these are of little consequence but others are critical. All assumptions are risks, so make sure you mange them as such. Especially, never assume you have the goodwill of the stakeholders or the resources to realise the benefits - check and confirm!

Blaming the formal project ‘process’ for slowing you down

It all depends on your culture. Formal in one company may be very bureaucratic whereas in another it may be very light. What a project manager needs to do to complete the project is the same in both circumstances.

What differs is the amount of trust that exists in the culture. The less trust there is, the more likely people are to demand ‘paperwork’ backing up every decision and recording every agreement. So, before you throw out the essential controls you need, consider whether it’s really a symptom of your culture that you need to address!

© Robert Buttrick