Ruth Murray-Webster, Peter Simon and Sergio Pelligrinelli

Many reasons have been put forward for why projects frequently overrun, exceed budget or under-achieve in terms of scope or quality, or fail to deliver the anticipated benefits. Some of the commonly cited culprits are poor practices in terms of planning and estimating and human biases towards optimism or perceived control of events. This, though, is not the whole story. Competent managers under-perform despite knowing about the pitfalls and the cognitive traps.

Many reasons have been put forward for why projects frequently overrun, exceed budget or under-achieve in terms of scope or quality, or fail to deliver the anticipated benefits. Some of the commonly cited culprits are poor practices in terms of planning and estimating and human biases towards optimism or perceived control of events. This, though, is not the whole story. Competent managers under-perform despite knowing about the pitfalls and the cognitive traps.

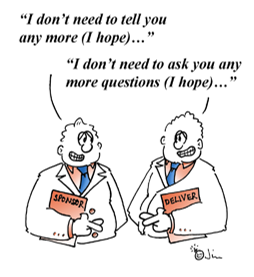

In this Lucid Thought we suggest that there’s another cause – something we’ll call professional posturing. This is something we’ve observed particularly when client organisations contract project-based services from a supplier that is paid to deliver specific outputs. We see such contexts constraining sharing of information, collaboration and mutual support. Sometimes the same effects are seen within the same enterprise where department boundaries, cultural expectations and professional norms create barriers to the admission of ignorance and the frank exchanges of doubts and concerns.

To understand how professional posturing arises, we need to look at the contracting process. This has the hallmarks of a mating ritual – obvious in the case of separate organisations, more subtle and disguised when it occurs within the same organisation. The engagement process starts off at armslength with the parties establishing their positions, exchanging information and testing each other. A brief collaboration is brought to an end by a presumed mutual understanding, to be replaced by a call for action and role demarcation. The various parties often presume that the other(s) can better see through the remaining fog of uncertainty, or that it will clear quickly (and favourably) as the project unfolds.

This is further complicated by an understandable temptation of sponsors to withhold direction and advice; understandable because it’s a way of testing the competence of those who will deliver. Sharing ‘internal’ tensions, doubts or misapprehensions is not conducive to establishing a position of authority. The felt need to show leadership and to be in control can lure sponsors into making more definitive statements and claiming more influence than the situation might warrant.

The desire to create personal contingency and to protect themselves often results in sponsors setting (overly) ambitious timescales, (excessively) tight budgets and (unreasonably) stringent performance parameters. Similarly, those in the delivery organisation feel obliged to establish credibility and demonstrate confidence.

Asking questions is frequently perceived as a sign of weakness and ignorance, so there is insufficient exploration of the purpose of the work, the real constraints and the implicit assumptions. An expeditious form of words is agreed to define the work, which does not have enough meaning for any of the parties. The exact scope of the project and nature of the deliverables become subjects of confusion, interpretation, tension, negotiation and compromise.

Because the conduct of the project is rarely discussed in sufficient depth: sponsors presume the professionals know how to do it, and the project professionals presume that their normal implementation methods and practices can be applied. The nuances of the work and the context are finessed, and so risks are unwittingly accepted. A lack of intimate knowledge combined with the desire to assume control of delivery can make it difficult for a project manager to ask for specific support or to judiciously allocate some activities to sponsor personnel, who would be far better placed to do the work.

Plans and estimates are often given a gloss of robustness that is, in fact, an illusion. Signs of hesitation or uncertainty in the project team are typically suppressed. This fuels the expectation that the project manager and team will drive the work and be self-sufficient, at times disengaging those within the sponsoring organisations whose knowledge and insights are invaluable. The aura of professional know-how that shields against critical scrutiny also deters helpful suggestions.

The professional and subject matter expertise embedded within the supplier/delivery organisation contributes significantly to ‘selling’ the project. It is often a differentiator and a deal winner, so is displayed to the full. Unfortunately, it does not always reside in, and often is not easily accessible by, the project team.

The more know-how and depth of intellectual capital claimed, the more the sponsor is led to believe that the project is more straightforward that it actually is, and that the team’s work is primarily about application and/or (minor) customisation. The need to develop things from scratch, or the effort and difficulties of adapting processes, technologies or assets to fit the sponsor’s precise needs or operating reality becomes difficult to justify.

Sponsors, having bought the ‘sales pitch’, are reluctant to give in to requests for deferrals or additional funds. This would call into question their choice of supplier (duped) or their ability to exert control (push-over). With their managerial reputations at stake, sponsors’ irritation, posturing and/or pressure may be understandable, but are rarely constructive. The project manager’s retort, whether voiced or just thought, is usually that the sponsor is naïve, arrogant and/or a bully.

The parties may seek to exert control and defend their professional judgements and positions. Unchecked, professional posturing can descend into cynical game playing and manipulation. Any ambiguity over the deliverables, the delivery model and/or the acceptance criteria is fought over and exploited. Rarely are there any winners in the long run.

We argue that there is another way – but it’s a way that demands some different personal skills and attributes. While you might argue that humility, modesty and acknowledged ignorance are not the most valued attributes in a professional arena, especially a competitive one; we would argue to the contrary.

We see that in a shifting, demanding and complex delivery environment, such personal qualities (not weaknesses) may be far less detrimental to true project success than the bravado and false assuredness exhibited by some project professionals. It’s just that to build relationships and deliver quality services by adopting a humble, modest and inquiring posture takes far more personal application than falling into the more normal trap of pretending all is well.

We leave you with a final thought. I don’t know what you don’t know – if you say nothing I will assume you know everything – if I don’t find a way of exploring my assumption then we will all fail.

Maybe ‘professional’ posturing is not so professional after all?

- © Lucidus Consulting

- www.lucidusconsulting.com