by Pat Weaver

Niels Bohr’s quote, “Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future” neatly encapsulates the challenges facing project controls professionals every working day if they are actively contributing to a successful project outcome. The question posed in this post is how accurate do we need to be with our projections to be useful? On one measure at least, accuracy of 98% is not sufficient!!

Niels Bohr’s quote, “Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future” neatly encapsulates the challenges facing project controls professionals every working day if they are actively contributing to a successful project outcome. The question posed in this post is how accurate do we need to be with our projections to be useful? On one measure at least, accuracy of 98% is not sufficient!!

The starting point is understanding what has occurred on the past and the ‘current status’ project. This is relatively easy, but is also a complete waste of time unless the data is interpreted in a model and use to provide useful information that helps the project management make decisions about future actions. This challenge applies to most aspects of planning and control from strategic planning at the corporate level through the full spectrum of project controls.

Virtually every project has a cost plan and a time plan (schedule) and many have other ‘plans’ designed to model future outcomes. The way project controls work is to build a ‘model’ of the project in a software tool focused on one or more aspects of the project and then use insights from these models to help management make better choices. To be useful the plans need to be dynamic and built to respond to inputs on both the progress achieved to date and future actions so the effect of proposed or anticipated changes can be modelled and the information derived from the model used to inform management decisions. Unfortunately this is where the problems occur.

As a starting point, as Professor George E.P. Box succinctly stated several years ago; ‘all models are wrong’! This is a risk for management using any model but as Thomas Knutson and Robert Tuleya said; “If we had observations of the future we would trust them more than models, …… unfortunately observations of the future are not available at this time.” The ‘model’ is all we have.

Therefore to be useful, the model needs to provide insights at are practical and reasonably reliable. The challenges are:

- building a realistic, dynamic model (eg, a dynamic schedule);

- validating the model which can be difficult given the unique nature of each project;

- having management make use of the insights derived from the model’s information.

In a project this largely boils down to the skill of the scheduler or cost planner and the confidence management have in their planners and their processes.

In the wider world, a similar debate is occurring around climate change. One of the first debates was around the depletion of ozone levels in the atmosphere caused by chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and other halogenated ozone depleting substances creating the ‘ozone holes’. Sherwood Rowland, the Nobel Prize winner who discovered the chemistry that led to ozone depletion, asked this question: “What is the use of having developed a science well enough to make predictions if, in the end, all we’re willing to do is stand around and wait for them to come true?”

Fortunately over time the world’s governments listened, CFC have been largely eliminated from society at large and the ozone is on a ‘bumpy road to recovery’.

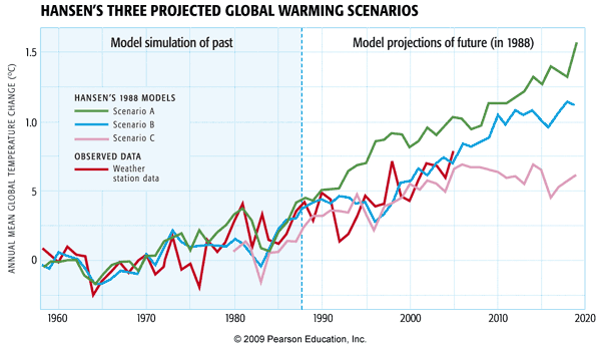

A similar consensus to make difficult decisions about climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions has not yet happened. The scientific view is virtually unanimous (at around 99%) the modelling is accurate and validated but for many politicians short term personal ‘political advantage’ overrides the need to make hard decisions focused on the long term good of society at large. There is a very interesting TED talk on the modelling of climate change. It highlights the destructive stupidity of the new Australian Government in the way it is ignoring both economics and science to attempt to cancel virtually all of Australia’s current climate change initiatives on ideological grounds – particularly given our position as one of the worst emitters per capita in the world.

At a more fundamental level though is the ‘controls’ question. How do we develop, use and promote effective modelling in the form of schedules, cost plans and other techniques and then use them to enable managers to have the confidence to make hard decisions based on the predictive information we create? No schedule or cost plan is going to achieve the 98% certainty achieved by the current climate models. If politicians and some business leaders can dismiss a 98% certainty of climate change as being unreliable to facilitate short term personal gains and avoid making prudent decisions that are needed to save lives; what chance do we stand with project management when the accuracy of our models is lower, the opportunity for validation almost non-existent and the consequences of ‘not deciding’ far less traumatic??

Studies consistently show good use of project controls makes for significantly improved project outcomes! They also show most projects, and virtually every ‘failed project’ did not make good use of project controls. There seems to be a wilful desire to create failure based on some perceived short term benefits achieved by not investing in effective control systems (people and processes). My question is how do we change this????